The Berlin Wall (44 page)

Authors: Frederick Taylor

‘Little’ Honecker and ‘Big’ Kohl, Bonn, September 1987

The Brandenburg Gate, 1980s

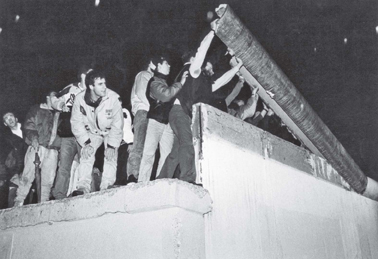

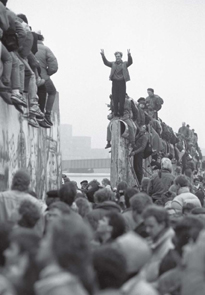

The end of the Wall, November 1989

More tightening of the border regime was, however, obviously required. On 14 September, on Ulbricht’s personal order, the borderpolice brigades in Berlin-38,000 men-were transferred from the Ministry of the Interior to the Ministry of Defence. What had been police units became soldiers, subject to military discipline. A new military post was created, city commandant of Berlin, a major-general in the NVA who reported to the Minister of Defence, Hoffmann.

There was another reason for imposing military discipline. Escape attempts were not confined to determined civilians. In less than a month after the barrier went up, 68 members of the special police units deserted to the West. Thirty-seven fled individually, like Conrad Schumann, while of the rest, a dozen cases were of two guards escaping together, with one group of three and another of four all deciding to go West.

These escapes represented a considerable achievement of planning on the part of the escapers. Superior officers, NCOs and

Stasi

were constantly probing what was being said and discussed in the guard posts, the barrack rooms and the canteens, with the aim of nipping such attempts in the bud. All but 3 of the police deserters were between 18 and 21, therefore likely to be single and without responsibilities or dependent family members who might suffer as a result of their actions. Most were not active anti-Communists. Three were SED members, 47 had belonged to its youth movement. The report on this problem blamed poor leadership, the fact that many of these units had been formed only a few weeks before 13 August, and-as usual when all else failed-‘insufficient political education’.

27

At 8.30 a.m. on 20 September, there began a special meeting of the Central Staff, presided over by Honecker. Here the ‘inadequacies in the border security system’ were stated frankly on the agenda. Honecker sternly told the assembled ministers and officials that ‘All attempts at breaking through must be rendered impossible’. They discussed the proposed new‘ 18-20-km. border wall’, plus the creation of anti-vehicle ditches to prevent escapes by truck or bus, an increase in the erection of upright concrete slabs and barriers, the sprinkling of sand on the border approaches to make detection easier, and the barring of the inter-sector sewer system, through which several spectacular escapes had already been made.

28

Surprisingly, not all ministers supported the idea of a wall.

Stasi

Minister Mielke thought a barbed-wire barrier would be ‘more durable and suitable for the prevention of border infringements’, while Defence Minister Hoffmann was in favour of a system mostly composed of ‘concrete blocks and ditches’. It was thought by these powerful and expert advocates of caution that in non-built-up areas a wall would throw shadows beneath which escapers could conceal themselves, thus negating the solid advantages of concrete.

Ulbricht’s support for the ‘border wall’ none the less proved decisive. It was his contention that barbed wire ‘tempted people and provoked them into more and more attempts to break through the border’.

29

There was soon confirmation of this. In the first week of October, a 260-yard stretch of post-and-barbed-wire fencing on the so-called ‘green border’ between Gross-Ziethen, in the East near Schönefeld Airport, and the district of Lichtenrade on the far-south-eastern rim of West Berlin, was actually torn down, leaving this part of the border wide open. To the

Stasi

’s alarm, border troops in the area did not even notice this was happening.

The barrier that would become the Wall was therefore taking shape, in large part simply in response to the continuing determination of East Germans to escape to the West, no matter the cost. The leadership was astonished and dismayed by the large number of escapes still being attempted. This was happening despite the obvious risk and despite the leadership’s best efforts, as well as those of the tens of thousands of police, soldiers and work parties striving to make the border impassable.

For similar reasons, another threshold was quietly crossed. The instructions to GDR border troops of July 1960 had circumscribed the use of firearms, laying out a careful escalation of warning instructions and shots before guards could fire at the person of a would-be escaper—preferably aiming at the legs. But in fact, from the third week of August 1961, a

de facto

shoot-to-kill policy was in effect. The self-righteous gloating over the deaths of Günter Litfin and Roland Hoff indicated a clear change in the border regime to one of ultimate force.

At the 20 September meeting, a secret order declaring that ‘firearms are to be used against traitors and violators of the border’ made the situation quite clear.

On 6 October the Minister of Defence, under whose control the border forces now stood, issued an order in which he stipulated: ‘A firearm may be used to the extent that is required for the purposes to be achieved.’ The main ‘purpose’ was to stop the fleeing individual reaching Western soil at all costs.

A third fatal shooting took place on 12 October at a railway goods station bordering West Berlin, where two young Easterners were spotted in the small hours of the morning, trying to force a grille and escape across the border. When challenged they ran off back into the Soviet sector, but guards shot one of them, twenty-year-old Klaus-Peter Eich, anyway, inflicting a fatal wound. The other escaper, though pursued with dogs, managed to evade capture. So now even attempting to ‘desert’, and turning back, could be punished with death. It was another ominous development.

It came as no surprise that neither then nor later were any members of the GDR’s armed forces tried for reckless use of firearms, manslaughter, or murder. The message was quite simple. All means necessary were to be used to hinder escape attempts, and if the authorities suspected that any border guards had deliberately allowed an escape, harsh disciplinary consequences would ensue. Ulbricht himself made his will brutally clear in a speech to Free German Youth officials: ‘Whoever provokes us, we shall fire on them…Many say that Germans just can’t shoot at Germans. (But) if we are dealing with Germans who represent imperialism, and they become insolent, then we shall shoot them…’

30

The sole stipulation modifying border guards’ freedom of action was simple: they must not under any circumstances open fire on West Berlin territory, so as to avoid international incidents. Otherwise, if an escape was foiled, by whatever means, promotions, medals and pay increases were the order of the day. It was hardly surprising, therefore, that members of the border-control forces tended to shoot at escapers in a way guaranteed to disable and likely to kill.

31

So the knot began to tighten. October would bring the XXII. Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) in Moscow, a huge international showcase for the international Communist movement.

Ulbricht hoped that Khrushchev would use the congress to formally announce the signing of a peace treaty with East Germany, and therefore the assumption by Ulbricht’s government of all the powers in the Soviet Zone and the Soviet sector of Berlin exercised since 1945 by the Russian occupiers. Then Ulbricht would be free to squeeze West Berlin without restraint.

HIGH NOON IN THE FRIEDRICHSTRASSE

AWAY FROM THE CAULDRON

of Berlin, the world carried on. In West Germany, of course, a rancorous election campaign was still in progress.

The day after Vice-President Johnson left, on 22 August, Adenauer appeared in West Berlin. Naturally, as protocol demanded, the ruling Chancellor was received by Mayor Brandt. Photographs of them together show the men looking away from each other, their faces impassive. When the old Rhinelander viewed the closed border at the Brandenburg Gate, he was greeted with catcalls and boos—and that was just from the Western side.

What happened on 13 August had presented Adenauer and his CDU government with a serious problem. Their policy on German reunification, which the Chancellor had pursued throughout his dozen years in office, was suddenly revealed as bankrupt. Through the so-called ‘Hallstein Doctrine’

1

, which stipulated that West Germany would not enter into relations with any country that recognised East Germany (the USSR being the only exception), Adenauer had tried to isolate the Communist regime. Through insisting on the status of West Germany as the sole legitimate German state, and Berlin as German capital-in-waiting, he kept alive the idea of a unified country. And through the so-called ‘magnet theory’, according to which in the longer term East Germany must be drawn into the orbit of the progressively richer, more dynamic and more powerful West Germany, Adenauer had promised his people the inevitable collapse of the Ulbricht regime.

After the primitive, brutally effective action of the Ulbricht/Khrushchev axis in Berlin—and the clear failure of the ‘big three’ Western occupation powers to oppose it—Adenauer and his ministers stood naked

and helpless. Perhaps because of this, the Chancellor’s trip to West Berlin was brief and fairly inglorious.

The election campaign continued. Adenauer grimly went on beating the increasingly hollow drum of conservative nationalism and blowing the rather more convincing trumpet of continuing economic success. His goal was to rally his hitherto reliable support among the vast middle class that had benefited from the post-war ‘economic miracle’ for which his government could claim credit. But the old fox no longer showed his habitual sureness of touch. The notorious and widely derided ‘Brandt alias Frahm’ speech was one example. In another bizarre outburst, this time in the Westphalian town of Hagen, Adenauer even characterised the Wall as ‘deliberate electoral help on Khrushchev’s part for the SPD’.

2

In the elections on 17 September, Brandt failed to unseat Adenauer. The West Berlin Mayor and his supporters had hoped that the Wall crisis and his new status as a national figure above party politics would help the SPD out of the working-class electoral ghetto in which it had languished throughout the 1950s.

None the less, Brandt’s party gained more than 4 per cent in the polls. Adenauer’s CDU lost almost 5 per cent and its overall majority. The big winner was the business-orientated Free Democratic Party, which won over middle-class voters who saw the bankruptcy of the old Chancellor’s policies but remained nervous of going all the way leftwards and voting for Brandt’s ‘Reds’. With almost 13 per cent of the vote, it held the balance. The problem was, the FDP had declared that it would not go into coalition with a government led by Adenauer.

After 17 September 1961, West Germany found itself in a situation of chaotic interregnum. Negotiations for a coalition government would last two months, eventually concluding only when 85-year-old Adenauer promised to step down midway through the government’s four-year term, to make way for a younger man.