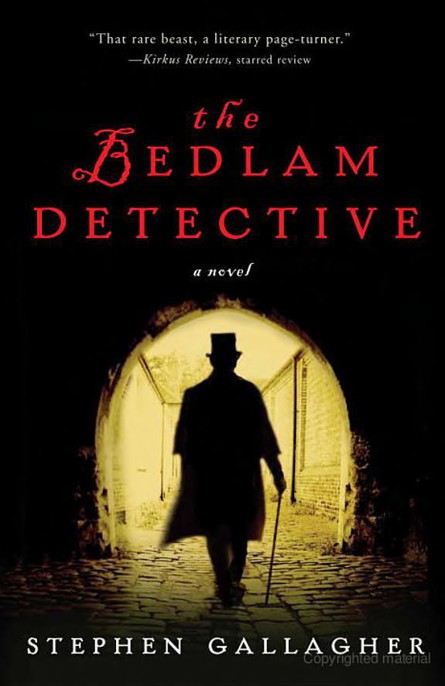

The Bedlam Detective

Read The Bedlam Detective Online

Authors: Stephen Gallagher

Tags: #Fiction, #Mystery & Detective, #Historical, #Thrillers, #Suspense, #Psychological

A

LSO BY

S

TEPHEN

G

ALLAGHER:

Chimera

Follower

Valley of Lights

Oktober

Down River

Rain

The Boat House

Nightmare, with Angel

Red, Red Robin

White Bizango

Out of His Mind

The Spirit Box

The Painted Bride

Plots and Misadventures

The Kingdom of Bones

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Copyright © 2012 by Stephen Gallagher

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Crown Publishers, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

www.crownpublishing.com

CROWN and the Crown colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Gallagher, Stephen.

The bedlam detective : a novel / Stephen Gallagher.—1st ed.

p. cm.

1. Private investigators—England—Ficiton. 2. Rich people—England—Fiction. 3. Eccentrics and eccentricities—Fiction. 4. Murder—Investigation—Fiction. I. Title.

PR

6057.

A

3

B

93

B

43 2012

823’.91—dc22 2011018605

eISBN: 978-0-307-95278-3

Jacket design by Whitney Cookman

Jacket photography © Stephen Mulcahey/Arcangel Images

v3.1

Contents

It is no good casting out devils. They belong to us,

we must accept them and be at peace with them.

D. H. L

AWRENCE

The Reality of Peace

1917

S

EBASTIAN

B

ECKER’S TRAIN HAD BEEN STANDING IN THIS LITTLE

English rural stop for fifteen minutes or more. When he looked out through his compartment’s window the view fogged and cleared, fogged and cleared, adding an illusion of movement as the locomotive’s idling boiler vented its unused energies and a breeze drove the cloud vapor on down its flanks. Sebastian saw a landscape of field and hedgerow, hedgerow and West Country field, all the way out to the blue distant hills.

There was a railway guard working his way down the platform toward them, stopping at each compartment to ask the same question.

A glance around Sebastian’s companions in first class showed strangers, all. A fat man in tweeds. Two clerical men, and a woman with a child. The child was about eight years old and wore a sailor suit, much as Sebastian’s own son once had. A pint-sized sailor, on his way to the seaside. The plush fabric of the seat made the child’s bare legs itch. Whenever he squirmed his mother would reach for his arm and shake him, once, in silent remonstration.

She was a widow, still in the attire. The boy was pale and blue, like the cloth of his suit. It was as if he were his father’s only memorial, and she exercised her grief by keeping him scrubbed down to the marble.

She met Sebastian’s eye.

“Forgive me,” he said, and once more looked out the window.

How far were they now, from the sea? Fifteen, twenty miles?

The sprung latch on the carriage door opened with a sound like the bolt of a rifle. The door swung out and the train guard hauled himself up to stand on the footboard. He’d bypassed the third class compartment next door.

He was a man of some girth, and he was shining with perspiration. His thinning hair was the dark brown of a much younger man, but his thick mustache was mostly gray and ginger. He wore a watch chain and waistcoat and the uniform of the Great Western Railway.

“Pardon me,” he said breathlessly. “But is anyone here a medical man or an officer of the law?”

He spoke to the company in general but when his gaze lit upon Sebastian, his manner changed.

No one moved.

“I thought perhaps you, sir?” the guard persisted when Sebastian made no response.

Sebastian Becker could sense the eyes of everyone in the compartment upon him.

“I’m sorry, but no,” he said.

The guard seemed to hesitate, as if about to say something else. Then he accepted the rebuff and moved to withdraw.

One of the clerical men called after him.

“Excuse me,” he said, “but why have we stopped?”

“Just a slight problem in the baggage car, sir,” the train guard said. “The stationmaster and I are having a difference of opinion over what’s to be done about it.”

The door closed with a bang. And that was that.

There was some shifting and throat-clearing in the compartment, but apart from something murmured by the fat man no one spoke. Back in America, Sebastian thought, the guard’s departure would have been the cue for some lively speculation and debate between strangers. But here, there followed a strained and British silence.

The guard was repeating his question next door to the third class people, this time with no

Pardon me

.

Sebastian opened his book and pretended to read, but it was of no use.

Eventually he closed the book and got to his feet.

“Excuse me,” he said, and opened the compartment door to climb down after the guard.

S

EBASTIAN HAD

once seen half of a man’s head blown clean off, gone from the eye sockets up. It had been done from behind, with a shot from a hunting rifle at a range of inches. Two men held the victim’s arms and forced him to kneel. The man with the rifle called a warning as he fired, so that his friends might turn their faces away—not to be spared the sight, but to avoid the spray. Sebastian could do nothing. He was part of a mob that had, only minutes before, been a peaceful labor meeting. To drop his disguise would have been certain suicide.

Although his evidence had later helped to hang two of the men, the hour stood in his memory as one of shame. He might have intervened; he had not. The fact that he was a Pinkerton man and undercover, and that the mob would have turned on him in an instant, somehow counted for little after the event.

Others agreed. Complete strangers were generous with their views on how he could and should have acted.

You could of said something abt. the sky and then taken the gun off the shooter when he was looking up and turned it onto him

, wrote one correspondent.

That is surely what I would of done in yr place

. And after his court appearance, another with differing loyalties wrote,

On your word two good men will hang. The scab only got what he deserved and some day so will you

.

A return to England, the land of Sebastian’s birth, had been Elisabeth’s idea. She sold her jewelry to buy them steamer tickets. It meant a fresh start, but a step down in fortune. Sebastian Becker now lived in London, and drew his modest pay from the coffers of England’s Lord Chancellor.