The Beatles Are Here! (3 page)

Read The Beatles Are Here! Online

Authors: Penelope Rowlands

With the Beatles,

the group’s second album, but the first truly great one, was released in the UK on November 22, 1963, the day John F. Kennedy was murdered. My father, the son of Irish-Catholic immigrants who arrived in a nation that despised them, never recovered from JFK’s assassination. He took Kennedy’s murder personally, sensing perhaps that Kennedy would be the last Irish-Catholic president he would see in his lifetime. When I was older, I was struck by the irony in this, because I have always believed that the Beatles’ stupendous success in America was directly related to JFK’s death. I remember reading this theory years and years after the fact and thinking, “Yes. Here is one theory about pop culture that is not stupid or obvious.”

The Beatles helped heal America. Or at least young America. Or at least most of young America, because there were still plenty of people in Dixie who were more than happy to see JFK go. Healing is what music does best. It stops the bleeding. The Beatles did not stop the bleeding all by themselves; the Supremes, the Miracles, the Temptations and the Four Tops pitched in too. But the Beatles got the process started. Some musicians heal ethnic groups. Some musicians heal nations. The Beatles healed an entire planet.

People love to romanticize the 1960s, but the only part of it you could actually enjoy was the music. Everything else was hell. Lynchings. Assassinations. Vietnam. George Wallace. Nixon. Jersey Boys. At least that is my take on it.

The first song I ever paid the slightest bit of attention to was “She Loves You.” I heard it right around Christmastime in 1963. I was thirteen years old. It was the first time in my life I heard a song that seemed to speak directly to me and not to adults. To this day, as much as I love “Honky-Tonk Woman” and “Purple Haze” and “White Rabbit,” I still think that “She Loves You” is the greatest song ever written. For me, it is and always will be the song that changed the world. I love that song. I absolutely love it. And with a love like that, you know you should be glad.

Greil Marcus, rock critic

ONE THING

I

will never forget about being a student [at the University of California, Berkeley] was reading in the

San Francisco Chronicle

that this British rock ’n’ roll group was going to be on

The

Ed Sullivan Show

. And I thought that sounded funny: I didn’t know they had rock ’n’ roll in England. So I went down to the commons room of my dorm to watch it and I figured there’d be an argument over what to watch. But instead there were 200 people there, and everybody had turned up to see

The

Ed Sullivan Show

. “Where did all these people come from?” I didn’t know people cared about rock ’n’ roll. I thought it was quite odd. . . .

. . . I go back to my dorm room and all you’re hearing is the Beatles, either on record or coming out of the radio. I sit down with this guy who’s older than me—he’s a senior, I’m a sophomore—and he was this very pompous kind of guy, but I’ll never forget his words. It was late at night and he said, “Could be that just as our generation was brought together by Elvis Presley, it may be that we will be brought together again by the Beatles.” What a bizarre thing to say! But of course he was right. Later that week I went down to Palo Alto—I had grown up there and in Menlo Park, on the Peninsula—and there was this one outpost of bohemianism, a coffeehouse called Saint Michael’s Alley, where they only played folk music. But that night they were only playing

Meet the Beatles

. And it just sounded like the spookiest stuff I’d ever heard. Particularly “Don’t Bother Me,” the George Harrison song. So the spring of ’64 was all Beatles. But the fall [when the Free Speech Movement erupted on the Berkeley campus] was something else.

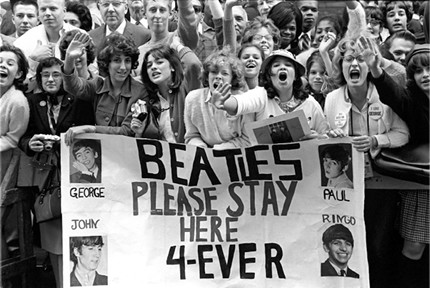

We Saw Them Standing There

by Amanda Vaill

IN

FEBRUARY OF

1964 I was a boarding student at Madeira, a girls’ school on the Potomac River, west of Washington, D.C. A bookish, rather nerdy adolescent from New York City, I’d grown up the only child of two increasingly estranged parents. As a minority of one I necessarily absorbed my parents’ tastes because, at home at least, there was little to set against them. I knew virtually nothing about popular music, or the culture that spawned it. I would rather listen to Ravel than the Ronettes; and while I wished like anything that I could have been on a barge in the Thames to hear the original performance of Handel’s “Water Music” back in the eighteenth century, I had absolutely no experience of (and professed to have less interest in) the dating rituals described in Lesley Gore’s hit single “Judy’s Turn to Cry.” When my classmates listened in rapture to Frankie Valli and Bobby Vinton, I gritted my teeth; I hated these teen heartthrobs’ amped-up accompaniments and melismatic vocalizing.

Back in November, though, thumbing through a copy of

Time

magazine during study hall instead of doing my Latin declensions, I’d read about a group of young rockers from Liverpool who were convulsing Great Britain, and had just played for the Queen Mother and Princess Margaret at the Royal Variety Performance, where their lead singer, John Lennon, had had the audacity to crack a joke: “For our last number,” he’d said, with a Liverpudlian burr, “I’d like to ask your help. The people in the cheaper seats clap your hands. And the rest of you, if you’d just rattle your jewelry.” I thought that was pretty cheeky and pretty classy at the same time. And in their photographs, this group, who called themselves the Beatles, looked both those things, with their modishly mod close-fitting jackets, their dark skinny ties and sharp white shirts, their mops of long but well-groomed, squeaky-clean hair (no Vitalis-slicked pompadours for them). It didn’t hurt that they were English, too—I was the worst sort of snotty Anglophile, able to name all the English kings from William the Conqueror on, but wobbly on the American presidents.

As Beatlemania had become an entrenched phenomenon and a signifier of hipness, some of my more enterprising schoolmates had managed to acquire copies of the first Beatles single to appear in the United States; and when we came back from Christmas vacation the dormitory hallways throbbed with the sound of Ringo Starr’s drums and John Lennon, Paul McCartney, and George Harrison protesting that they wanted to hold our hand. The sound was nothing like any of the American rock ’n’ roll I had heard, despite the electric guitars and the 4/4 beat. The harmonies were bright and fresh, the drum track as filigreed as a Bach fugue, and the sound was direct, unfussy, unengineered. I, who had had no use for Elvis or the Kingsmen or the Crystals, became infatuated.

Maybe it had something to do with the fact that most of their songs seemed so forthrightly joyful, and we all—certainly my schoolmates and I—needed a little joy just then. It had been only a little more than two months since we’d been stunned by the news, on a bright autumn Friday, of John F. Kennedy’s assassination in Dallas. The whole nation was in shock, but the blow hit particularly hard at Madeira, where so many girls were the daughters of congressmen, senators, and diplomats. We’d heard about it in midafternoon, and in the early evening a few of us gathered in the Wing Library, a gracious paneled room whose windows overlooked the twilit river, to talk and comfort one another. At one point we became aware of the quiet snarl of an airplane in the distance, the sound growing louder as it passed overhead, then diminishing as it flew over the river to Maryland. All air traffic around the capital had been shut down in the uncertainty following the assassination, so there was only one plane it could be: Air Force One, carrying two presidents, one alive and one dead, back to Washington. Suddenly no one wanted to talk any more.

Just over two months later, on Sunday, February 9th, clad in the pastel shirtwaist dresses and Pappagallo flats we wore for dinner and for Sunday vespers, we crowded into that same room, where a small television set was tuned to

The Ed Sullivan Show

. Sullivan, a former gossip columnist with brilliantined hair and the mournful eyes of a funeral director, had become a household word—had even inspired a song in the Broadway musical

Bye-Bye Birdie

—by retooling the vaudeville variety-show format into a conduit that delivered the performing arts into more than fifty million living rooms across America. Every Sunday night at 8 p.m., from coast to coast, in a bonding ritual that helped to define popular culture in mid-century, Americans shared the experience of watching the opera divas, circus acrobats, Shakespearian actors, magicians, ballet dancers, pop singers, and standup comics that Sullivan deemed worthy of headlining his show. And tonight, in addition to a number by the zaftig British comedienne Tessie O’Shea and an excerpt from Lionel Bart’s musical

Oliver!

, Sullivan was introducing the Beatles, who had flown across the Atlantic for the purpose, to America.

When the broadcast studio’s pale damask curtains parted to reveal the “youngsters from Liverpool,” standing on a stark set composed of cutout arrows, Sullivan’s audience began to screech like a pack of gulls wheeling over a clam roll. “One, two, three, four!” came the count-in, and then the Beatles launched into the jaunty “All My Loving.” They shook their glossy hair—uncannily like that of the English moppets who had just performed “I’d Do Anything” from

Oliver!

—and the studio audience shrieked again. My pastel-clad peers and I looked at the screen as the TV cameras panned over the auditorium, normally full of people who looked like our parents, and what we saw was ourselves reflected back at us: teenaged girls and young women, dressed in proper little wool jumpers or tidy tailored suits with circle pins on the collar, all gasping and clutching their faces in paroxysms of innocent desire, primal but somehow not prurient.

The Beatles went on to perform “Till There Was You,” with a sweet, straight-up solo by Paul McCartney (naturally I had to be the one to point out that the Beatles hadn’t actually written that song—it was from the 1959 Tony-winning Broadway show

The Music Man

); then rocked into “She Loves You.” And that was the point when we all (me included) were truly transformed, singing along, shaking our hair, just like our sisters on the screen, as if we were caught up in something bigger than ourselves, a kind of movement, and this music was our anthem.

Sullivan’s show ended at nine o’clock, which happened to be when the bell sounded signaling it was time for us to return to our dormitories. This was not done by some rude electronic klaxon: instead a uniformed personage known as the Bell Maid, who normally sat behind the school’s 1930s switchboard, came out from her post, crossed the corridor, and tugged on a rope connected to a bell in the cupola high above. She was ringing her peal as we emerged from the Wing Library. We certainly didn’t think of it then, but in some ways, she was ringing a funeral knell for one era, our parents’, and ushering in a new one, which for better or worse belonged to us.

A Newspaper Article

by Gay Talese

Other books

Her Immortal Love by Diana Castle

Unfinished Dreams by McIntyre, Amanda

01 - Battlestar Galactica by Jeffrey A. Carver - (ebook by Undead)

On Every Street by Halle, Karina

Swallow the Moon by K A Jordan

English Horse by Bonnie Bryant

Swallow (Kindred Book 2) by Scarlett Finn

The Discovery, A Novel by Walsh, Dan

Playing With Fire by C.J. Archer

Fangboy by Jeff Strand