The Battle of Hastings (31 page)

Read The Battle of Hastings Online

Authors: Jim Bradbury

The change in the Church, if not so drastic as the changes in the nobility in terms of method, was as complete in terms of effect for the greater prelates. In the words of Barlow, ‘the English Church had come under new management’. English bishops were allowed to continue, but on their deaths were replaced by a continental group. By 1073 the bishops included eight Normans, four Lotharingians, one Italian and only two Englishmen; by 1087 there were eleven Normans and one Englishman. The change in the abbeys was not quite so drastic, but a similar process was observed in most of the greater houses, continental abbots replacing English predecessors.

Stigand was permitted to hang on until 1070, partly because of his submission. But in 1070 he was removed and replaced by Lanfranc as Archbishop of Canterbury. Lanfranc was not Norman, but he had received preferment in the Norman Church before the Conquest. He was a leading figure in the Church, a thinker, writer, teacher and reformer and a great Archbishop of Canterbury. But he was a whole-hearted supporter of the Conqueror’s regime.

Lanfranc also introduced Church reforms, with which he was already associated on the continent, into England. Such changes would no doubt have come into England without the Conquest in time, and we need not disparage the state of the Old English church. But as events turned, a number of significant reforms were introduced through the new episcopate and under the aegis of the new king.

It was also an age of great church building, and somewhat accidental that hundreds of the new stone churches either replaced older English buildings, or survived better than they did. There was also a centralising policy for episcopal sees. Where existing centres were in small and remote places they were often moved to a more urban and central position: Elmham to Thetford, Selsey to Chichester, Lichfield to Chester. This was a trend which had begun before the Conquest.

Leading churchmen played a major role in the Conqueror’s administration, and it is not surprising that they should keep their continental ways. This must be one reason that the documentation of government, in particular the charters, reverted to Latin from Old English. Again, one need not attack the state of English government, it is simply that the Conquest brought certain changes with it. Both England and Normandy had reasonable systems before 1066, and both contributed something to the Anglo-Norman state which emerged. But one cannot deny that the Conquest brought change which would not otherwise have occurred in the form it did.

Thus shires and hundreds and many other English institutions survived, but would there, for example, ever have been a Domesday Book had there not been a Norman Conquest? The answer is surely no. The English system could have produced such a work, and its contents owed a great deal to existing English practice and methods, but there would have been no need for quite such a document without the Conquest and no driving force behind it without the Conqueror. Thus we possess one of the great records from the eleventh century, an absolute godsend to historians, a fund of all sorts of information.

In conclusion, we may ask what were the main political effects of the Conquest? They are mostly obvious but this does not make them any the less important. For a start, there was a new king and this would soon be seen as the beginning of a new dynasty – to such an extent that a thirteenth-century king would be known as Edward I, disregarding the rule of the Old English monarchs of that name. The Conqueror made some claims about his right by descent, but it was right by force which everyone recognised.

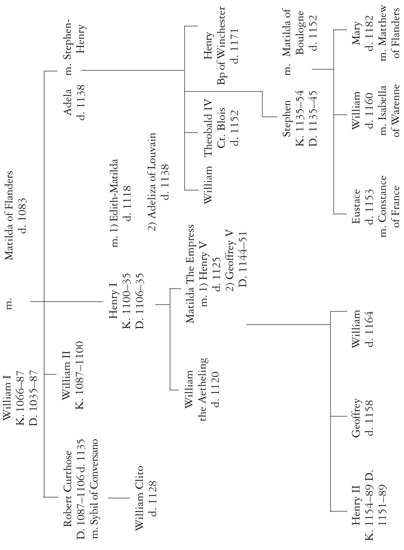

The Conquest had brought a new line to the throne. And for centuries, in some ways even till now, that has meant a king (or queen) of England who would not have been on the throne but for the events of 1066. More immediately, William’s reign in England was followed by that of his two sons, William II Rufus (1087–1100) and Henry I (1100–35); then by his grandson, Stephen (1135–54) and his great-grandson, Henry II (1154–89). For all the changes and problems of succession which the period 1066 to 1189 covered, it is still true that William’s line ruled in England, and of course would continue so to do.

Kings of England and Dukes of Normandy.

The imposition of a French nobility also had its effects. The new lords of England belonged to families which mainly held considerable lands across the sea. For some time, this would cause a new situation in English politics, and obviously affected the English nobility’s attitude to continental affairs. Out of this, as well as out of succession disputes, came an interweaving of affairs in kingdom and duchy. The two stayed tied in political matters for centuries. William as duke of Normandy conquered England in 1066; his son Henry I as king of England conquered Normandy in 1106.

It is probably true that the Conquest had some influence on the greater unity of England and on the dominance of England over its British neighbours. But both developments had begun before, and neither had dramatic improvement at once. It has reasonably been argued that despite the harrying, indeed partly because of it, the north was not truly ruled from the south for many years to come.

65

Northern separatism remained a factor in English politics long after William’s death. But it is probably true that the English magnates lost something of their powers relative to the king. No Anglo-Norman earl would quite equate in status to, say, Godwin of Wessex. The powers of earls diminished somewhat and the powers of royal authority within the earldoms increased.

The link between England and Normandy brought even more dramatic enlargement to the rulers of England in time. Henry of Anjou, son of the Empress Matilda, inherited Anjou from his father; Normandy from his mother, but made possible by his father’s conquest of it; and soon England. By various means he became lord of all western France, and what we know as the Angevin Empire was born. Out of that came inevitable conflict with the Capetian kings of France: the losses under King John, the revival in the later Middle Ages in the first stages of the Hundred Years’ War. Not until the fifteenth century was this conflict truly determined, so that France as we know it would emerge, and the English crown would be shorn of nearly all its hold on continental lands.

In some sense, all of this came about because of Hastings and the Norman Conquest. Indeed, it would not be untrue to suggest that English history from 1066 until now is a consequence of the battle of Hastings. It would not otherwise have been as it has been. It truly was a great and significant battle: it changed a crown, it changed a nation, and it deserves its reputation as one of the few occasions and dates which everyone remembers. If I decided the dates of national holidays, 14 October would be one of them.

Notes

1

. William of Poitiers, ed. Foreville, p. 210; N. Hooper, ‘Edgar the Aetheling: Anglo-Saxon prince, rebel and crusader’,

Anglo-Saxon England

, xiv, 1985, pp. 197–214.

2

.

Bayeux Tapestry

, pl. 71–2.

3

. William of Poitiers, ed. Foreville, p. 210.

4

. Thorpe (ed.),

The Bayeux Tapestry

, p. 54.

5

. Orderic Vitalis, ed. Chibnall, ii, p. 178.

6

. William of Poitiers, ed. Foreville, p. 204; Thorpe (ed.),

The Bayeux Tapestry

, p. 54.

7

. Swanton,

Three Lives of the Last Englishmen

, p. 13.

8

. Orderic Vitalis, ed. Chibnall, ii, p. 180.

9

. Orderic Vitalis, ed. Chibnall, ii, p. 180.

10

. William of Poitiers, ed. Foreville, p. 212: ‘

ad Fractam Turrim

’.

11

. Orderic Vitalis, ed. Chibnall, ii, p. 180.

12

. Whitelock

et al.

(eds),

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

, p. 144; Cubbins (ed.),

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

, p. 80.

13

. Orderic Vitalis, ed. Chibnall, ii, p. 182.

14

. J. Beeler,

Warfare in England, 1066–1189

, New York, 1966, pp. 25–33.

15

. F.H. Baring, ‘The Conqueror’s footprints in Domesday’,

EHR

, xiii, 1898, pp. 17–25; Baring,

Domesday Tables

; G.H. Fowler, ‘The devastation of Bedfordshire and the neighbouring counties in 1065 and 1066’,

Archaeologia

, lxxii, 1922, pp. 41–50; D. Butler,

1066: the Story of a Year

, London, 1966; A.M. Davies, ‘Eleventh century Buckinghamshire’,

Records of Buckinghamshire

, x, 1916, pp. 69–74; and J. Bradbury, ‘An introduction to the Buckinghamshire Domesday’, in A. Williams and R.W.H. Erskine (eds),

The Buckinghamshire Domesday

, London, 1988, p. 32. The idea goes back beyond Baring in origin, see J.J.N. Palmer, ‘The Conqueror’s footprints’. Palmer puts damaging questions against the Baring thesis, but does not draw the full conclusions, and has missed my 1988 comments.

16

. R. Welldon Finn,

The Norman Conquest and its Effects upon the Economy

, London, 1971, p. 19.

17

. William of Poitiers, ed. Foreville, p. 220.

18

. J. Nelson, ‘The rites of the conqueror’,

ANS

, 1981.

19

. Orderic Vitalis, ed. Chibnall, ii, p. 182–4.

20

. William of Poitiers, ed. Foreville, p. 230.

21

. Orderic Vitalis, ed. Chibnall, ii, p. 194.

22

. Orderic Vitalis, ed. Chibnall, ii, p. 218.

23

. Orderic Vitalis, ed. Chibnall, ii, p. 196.

24

. Baudri de Bourgueil, ed. Abrahams, p. 196.

25

. Orderic Vitalis, ed. Chibnall, ii, p. 196.

26

. William of Poitiers, ed. Foreville, p. 264.

27

. William of Poitiers, ed. Foreville, p. 266.

28

. Orderic Vitalis, ed. Chibnall, ii, p. 204–6.

29

. William of Poitiers, ed. Foreville, pp. 268–70.

30

. Orderic Vitalis, ed. Chibnall, ii, p. 208 has the last information clearly derived from Poitiers’ surviving manuscript, from then on we may expect material from Poitiers but only surviving in Orderic. This is made practically certain by Orderic’s comment, p. 258: ‘William of Poitiers has brought his history up to this point’: i.e. Orderic, pp. 208–58, must make use of the lost end section of Poitiers.

31

. William of Jumièges, ed. van Houts, ii, p. 178.

32

. Williams,

The Norman Conquest

, p. 24.

33

. Orderic Vitalis, ed. Chibnall, ii, p. 212.

34

. Orderic Vitalis, ed. Chibnall, ii, p. 216.

35

. Whitelock

et al.

(eds),

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

, p. 150.

36

. Kapelle,

The Norman Conquest

, p. 112.

37

. Whitelock

et al.

(eds),

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

, p. 150; Symeon of Durham in Stevenson, p. 550; Cubbins (ed.),

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

, p. 84.

38

. Symeon of Durham in Stevenson, p. 551.

39

. Orderic Vitalis, ed. Chibnall, ii, pp. 222, 230.

40

. Orderic Vitalis, ed. Chibnall, ii, p. 234.

41

. Symeon of Durham in Stevenson, p. 551.

42

. Orderic Vitalis, ed. Chibnall, ii, pp. 230–2.

43

. Whitelock

et al.

(eds),

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

, pp. 148–9, D and John of Worcester, eds Darlington amd McGurk, give sixty-four ships; Orderic Vitalis, ed. Chibnall, ii, p. 224 has sixty-six.

44

. William of Jumièges, ed. van Houts, ii, p. 182.

45

. It is not certain when she went, it may have been before the second raid, since John of Worcester has 1068. Orderic says she went to France, Worcester has Flanders – which seems more likely.

46

. Williams,

The Norman Conquest

, pp. 35, 49–50 and n. 21.

47

. Whitelock

et al.

(eds),

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

, p. 154.

48

. Orderic Vitalis, ed. Chibnall, ii, p. 258.

49

. Whitelock

et al.

(eds),

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

, p. 158.

50

. Orderic Vitalis, ed. Chibnall, ii, p. 318.

51

. Whitelock

et al.

(eds),

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

, p. 157; Cubbins (ed.),

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

, p. 87: ‘

wreide hine sylfne, 7 bæd forgyfenysse, 7 bead gærsuman

’.

52

. William of Malmesbury, ed. Stubbs, ii, pp. 313–14.

53

. Orderic Vitalis, ed. Chibnall, ii, p. 322; Symeon of Durham in Stevenson, p. 563, has an axe.

54

. Orderic Vitalis, ed. Chibnall, ii, p. 266.

55

. R.H.C. Davis,

The Normans and their Myth

, London, 1976; G. Loud, ‘The

Gens Normannorum

– myth or reality’,

PBA

, iv, 1981, pp. 104–16; M. Bennett, ‘Stereotype Normans in Old French vernacular literature’,

ANS

, ix, 1986, pp. 25–42. Searle,

Predatory Kinship

, suggests there was some reality to the ideas of a Scandinavian inheritance.