The battle for Spain: the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939 (75 page)

Read The battle for Spain: the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939 Online

Authors: Antony Beevor

Tags: #Europe, #Revolutionary, #Spain & Portugal, #General, #Other, #Military, #Spain - History - Civil War; 1936-1939, #Spain, #History

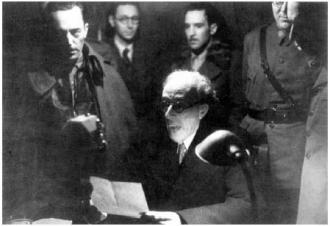

The anti-communist coup of March 1939, which ended the war. Colonel Casado (left) listens while Julián Besteiro broadcasts the manifesto of the National Council of Defence.

Republican refugees swarm across the French frontier in the Pyrenees, January 1939.

Republican prisoners in the French internment camp of Le Vernet.

19 May 1939. Condor Legion standard dipped in salute to Franco at the victory parade.

The indoctrination of republican orphans.

October 1940. Hitler and Franco meet at La Hendaye, a photo-montage after the event.

The Spanish Blue Division in Russia on the Leningrad front.

For the French government, which already had a bad conscience over the betrayal of Czechoslovakia, there was no choice. On 5 February it announced that the remains of the People’s Army could cross into France. Altogether, from 28 January around half a million people crossed the border. Another 60,000 did not arrive in time and fell into nationalist hands. Negrín witnessed the entry into France of the first units of the People’s Army. V and XV Corps crossed at Port-Bou; XVIII Corps at La Junquera; the 46th Division at Le Perthus; the 27th Division at La Vajol; and the 35th Division, which covered the withdrawal of the Army of the Ebro and XI Corps finally crossed the frontier near Puigcerdá, on 13 February.

The sight of these gaunt, shivering masses was often tragic and pitiful. But many observers noted that their manner was of men and women who still refused to admit defeat. Some republican units marched across and piled arms on French soil under the directions of the gendarmes while the colonial troops from Senegal stood with rifles at the ready, not understanding the situation. A

garde mobile

, in a scene now famous, prised open the fist of a refugee to make him drop the handful of Spanish earth which he had carried into exile.

36

The republican diaspora had begun.

The Collapse of the Republic

O

n 9 February, just as the nationalists completed their occupation of Catalonia, the republican government, forced from Barcelona into France, met briefly in Toulouse to discuss the possibility of continued resistance. At the end of the meeting Negrín received a message from General Miaja, who a few days earlier had been promoted and made commander of all three services, requesting authorization to start negotiations with the enemy to end the war.

1

Negrín made no reply.

Accompanied by álvarez del Vayo, he then managed to elude journalists before taking a chartered Air France plane to Alicante. On his arrival Negrín immediately had a meeting with Miaja, accompanied by Matallana who had taken over as commander of the armies in the remaining central and southern zone. Negrín wanted to know his reasons for starting negotiations. Only a few ministers, generals and senior officials returned to the remaining central-southern zone. Azaña was shortly to resign the presidency, when Great Britain and France recognized the Franquist regime, and his provisional successor, the leader of the Cortes, Martínez Barrio, refused to return to Spain.

Another meeting had taken place on 8 February in Paris. Mariano Vázquez, Juan García Oliver, Segundo Blanco, Eduardo Val and other CNT leaders had also come together to discuss the situation. For García Oliver, Negrín’s policies had been a resounding failure and in his opinion there was no alternative but to seek peace with the nationalists, although not at any price. It had to be an ‘honourable’ agreement and needed a new government to negotiate it. Eduardo Val, secretary of the defence committee of the central region, supported this, saying that Negrín had been telegraphing in code to his closest colleagues warning them to evacuate the republican zone. From this it appeared that Negrín was playing a dirty game. They unanimously decided to push for the formation of a new government from which Negrín would be excluded. On returning to Madrid, Eduardo Val, who did not have complete confidence in the determination of his comrades, decided to act on his own account.

2

During the first part of February the Comintern agent Stepánov tried to convince the cadres of the Spanish Communist Party in Madrid that the only course possible was a ‘revolutionary democratic dictatorship’.

3

He proposed to replace the government with a ‘special council of defence, work and security’, made up of two ministers and two soldiers, ‘reliable and energetic’,

4

not to make peace, but to continue the war and win it. The Madrid communists accepted this at their conference, which took place from 9 to 11 February.

La Pasionaria also declared her determination to win the war and came up with another of her slogans: ‘Spain will be the torch which will light the road of liberation for people subjugated by fascism.’

5

Palmiro Togliatti was dismayed. He tried to warn them of the divide between the leaders and the people, who were exhausted to the point of nausea by the war and only wanted to hear of peace.

6

Togliatti realized that the communists had lost support, largely because of the disastrous military strategy and because their methods had made them more enemies than friends. Officers, who had leaned towards the Party early in the war, now opposed them in secret. Many of them believed that the communists constituted the main barrier to peace. Above all, the commanders of the republican armies left in the centre had no illusions about their inability to resist any longer. The lack of armament was not as serious as in Catalonia, but they knew they had no chance against the crushing nationalist superiority in artillery, tanks and aircraft.

No assistance could be expected from the British. Chamberlain wanted the war to be finished as quickly as possible. On 7 February, with the collaboration of the nationalists, the British consul in Mallorca, Alan Hilgarth, arranged for the island’s surrender on board HMS

Devonshire

. The British simply wanted to make sure that the Balearic Islands remained Spanish, with no Italian presence.

7

On 12 February Negrín came to Madrid, where he summoned a council of ministers for the following day. During the session, Negrín called once again for the unity of the Popular Front and re-emphasized his decision to resist until the end: ‘Either we all save ourselves, or we all sink in extermination and dishonour.’

8

On the same day General Franco published in Burgos his Law of Political Responsibilities. Its first article declared ‘the political responsibility of those who from 1 October 1934 and before 18 July 1936 contributed to create or to aggravate the subversion of any sort which made Spain a victim, and all those who have opposed the nationalist movement with clear acts or grave passivity’. The law could thus apply to practically any republican, whether a combatant or not. The British consul in Burgos informed the Foreign Office that, in his opinion, the law gave not the slightest guarantee that those who had served in the republican army or been a member of a political party–which implied no criminal responsibility–would not be punished.

9