The battle for Spain: the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939 (51 page)

Read The battle for Spain: the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939 Online

Authors: Antony Beevor

Tags: #Europe, #Revolutionary, #Spain & Portugal, #General, #Other, #Military, #Spain - History - Civil War; 1936-1939, #Spain, #History

Colonel Wolfram von Richthofen (centre right looking at camera) with nationalist and Condor Legion officers.

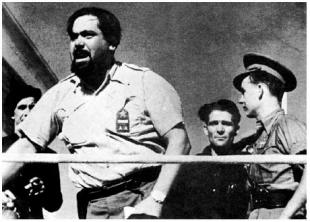

El Campesino making a speech.

Juan García Oliver broadcasts an appeal for calm during the May events in Catalonia.

6 May 1937. Assault guards brought in to restore order marching through Barcelona.

General Pozas and communist officers take over the Catalan council of defence, May 1937.

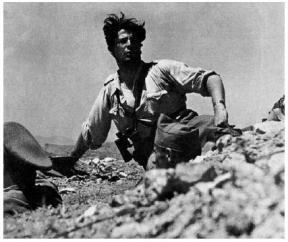

The Battle of Brunete, July 1937. Juan Modesto, the communist commander of V Corps.

Republican wounded at Brunete with T-26 tanks in the background.

The Falange, the Carlists, the Alfonsine monarchist

Renovacíon Española

and the remnants of other right-wing groups, like the CEDA’s Popular Action, were amalgamated by decree into one party under his direct orders.

4

The party was to be called the

Falange Española Tradicionalista y de las JONS

(Traditionalist Spanish Falange and the National Syndicalist Offensive Juntas). As the choice of name indicated, the Carlists came off worst in this forced union, with a programme based on 26 out of José Antonio’s 27 points.

5

But, as Franco had calculated, the Carlists were more obedient and less politically minded. The new uniform consisted of the Falangist blue shirt and the Carlist red beret. The fascist salute was officially adopted and the movement’s slogan was to be ‘

Por el Imperio hacia Dios

’ (For the Empire towards God). The Caudillo was proclaimed chief of the new party and his brother-in-law, Ramón Serrano Súñer, was appointed executive head. (This produced a new Spanish word,

cuñadismo

, meaning ‘brother-in-lawism’, as a variant on nepotism.) Serrano Súñer, an intelligent and ambitious lawyer who had been a friend of José Antonio, had become a vice-president of the CEDA, then moved towards the Falange in the spring of 1936. He was captured in Madrid after the rising and held in the Model Prison, where he witnessed the killings in revenge for the news of Badajoz. This experience and the death of his two brothers made him one of the most intransigent advocates of the

limpieza

after he escaped from hospital (in circumstances which have never been satisfactorily explained) and reached nationalist territory in February 1937.

6

The suddenness of Franco’s coup increased its effect. By the time the announcement had been fully appreciated, anyone who wanted to object only exposed himself to the charge of treachery towards the nationalist movement. Hedilla, somewhat unimaginatively, believed that he could maintain a position of power as the head of the Falange and guarantee its independence. He refused to join the council of the new party and tried to mobilize his supporters. He was arrested on 25 April, and condemned to death a month later for ‘a manifest act of indiscipline and subversion against the single command of nationalist Spain’.

7

On ˜er’s advice, however, the sentence was commuted to life imprisonment. In fact, he served only four years, but it was enough to remove him from any position of influence during a critical period. The new puppet council appointed by Franco was no longer challenged, after the rest of the Falange was rapidly brought into line by dismissals and about 80 prison sentences.

As commander of the most important formation in the nationalist army, the Army of Africa, Franco had started his climb to leadership from an advanced position. He had no effective rival and the very nature of the nationalist movement begged a single, disciplined command. As a result he had achieved supreme power in two well-timed stages: September 1936 and April 1937. With the first he became de jure leader; with the second, suppressing all potential opposition, de facto dictator. Now he was in position to tackle a long war and to construct his idea of what Spain should be.

A power struggle had also begun in republican territory during the winter of 1936 and the spring of 1937, although the winners, the communists, were never to achieve the same degree of power as Franco. They started from a very restricted base and their policies to centralize power were resisted by one of the major components of the republican alliance, the anarchists. At the same time the Valencia government was exasperated at its lack of control over independent regions, especially Catalonia and Aragón.

In December 1936 the central committee of the Comintern had met on several occasions to analyse the course of events in Spain and the position of the Spanish Communist Party. On 21 December Stalin sent a letter, counter-signed by Molotov and Voroshilov, to Largo Caballero. Stalin first of all underlined the fact that the republican government had asked for Soviet advisers to help them, and that the officers sent to Spain had been told ‘that they should always remember that, in spite of the great solidarity which now exists between the Spanish people and the peoples of the USSR, a Soviet specialist, being a foreigner in Spain, can be really useful only if he stays strictly within the limits of an adviser and adviser only’.

8

He then went on to emphasize the Comintern line that Soviet aid to republican Spain was to safeguard democracy and insisted that the government followed the popular front strategy, which helped landowning peasants and attracted the middle classes. In fact, Stalin was interested in avoiding any embarrassments to his foreign policy, which on one hand wanted to evade provoking Nazi Germany, and on the other to seek a rapprochement with Britain and France. A parliamentary republic should Serrano Su ´n be maintained ‘to prevent the enemies of Spain seeing her as “a communist republic”’.

Comintern agents were meanwhile instructed to construct a disciplined army, with a single command, to develop the war industries and achieve united action among all political groups. Codovilla was to convince Largo Caballero to bring forward this programme, a difficult task considering how bad relations were after the communists had taken over the Socialist Youth. The fall of Málaga and the arrival in Spain of the Bulgarian Comintern agent Stoyán Minéevich (‘Stepánov) were to put an end to such optimism. On 17 March Stepánov informed Moscow that the person ultimately responsible for the fall of Málaga was Largo Caballero because of his connivance with traitors on the general staff. The Comintern convinced Stalin that it was essential to remove Largo Caballero from the ministry of war and told the Spanish Communist Party to do everything necessary to ensure that “Spaak” [Largo Caballero] remained only as head of the government’.

9

The communist tactic was to block ministers from exercising control over the People’s Army. This they regarded as essential both in the interests of winning the war and in order to increase their own power. But the anarchists from the beginning had warned clearly that any attempt to impose non-anarchist officers on their troops would be met by force. Faced with such resistance, the communists solicited the support of regular officers. They approached the most ambitious, presenting themselves as the true believers in iron discipline and good organization. Experts in the manipulation of bureaucracy, they infiltrated their own members into key positions. They managed to place Lieutenant-Colonel Antonio Cordón as head of the technical secretariat of the ministry of war, where he controlled pay, promotion, discipline, supplies and personnel. They also removed Lieutenant-Colonel Segismundo Casado from the post of chief of operations on the general staff because he had denounced their machinations and they replaced him with a member of their own party. A report to Moscow in March 1937 reveals that 27 out of the 38 key commands of the Central Front were held by communists and three more by sympathizers.

10

Another report claimed later that ‘the Party therefore now has hegemony in the army, and this hegemony is developing and becoming firmly established more and more each day both in the front and in rear units’.

11

The communists set out to remove General Asensio Torrado, whom they called the ‘general of defeats’, accusing him of incompetence and treason. The most prominent attack came from the Soviet ambassador, Marcel Rosenberg. Since January 1937, Rosenberg had been behaving like ‘a Russian viceroy in Spain’, continually harassing Largo Caballero, telling him what to do and what not to do. On one occasion the old trade unionist had thrown him out of his office. The irony of the affair was that on 21 February, while the communists were still calling for Asensio Torrado to be shot, Rosenberg was recalled to Moscow, where he was executed soon afterwards in the purges. Although Rosenberg’s successor, Gaikins, played a less dominant role, he continued to urge the fusion of the socialist and communist parties, a step to which Largo Caballero was now completely opposed. Strong-arm tactics became less necessary at such a high level, because the Party controlled most of the bureaucracy.