The Battle for Gotham (9 page)

Read The Battle for Gotham Online

Authors: Roberta Brandes Gratz

Tags: #History, #United States, #20th Century

At the same time, I reported on housing, urban renewal, and community battles for survival, on small successes and large failures, on historic preservation and neighborhood revitalization. I saw government policies repeat the mistakes of the past because vested interests, misguided analyses, and wrongheaded plans stood in the way of appropriate urban change. And I saw neighborhoods rebuild themselves despite government-created impediments. What I learned about the dynamic of cities I learned first in the neighborhoods of New York and from the people who fought to save and renew their turf. Residents and business owners in any place, the essential users, instinctively know what is needed and not needed to keep their community healthy or to make it better.

I covered the fight to build low-income housing in middle-income neighborhoods and wrote with colleagues Anthony Mancini and Pamela Howard a six-part series, “The Great Apartment House Crisis.” I worked on another six-part series, this one about the newly opened Co-op City and its impact on the South Bronx, especially the Grand Concourse from which many of the residents had moved. I was stunned to observe such massive relocation out of one neighborhood into another. Later, I investigated shady landlords and cheating nursing home operators, covered hot zoning battles and ongoing urban renewal clearance projects, and investigated Forty-second Street property owners purposely renting to illicit uses to make a case for city condemnation and payout for their properties.

THE APPEAL OF HISTORIC PRESERVATION

Historic preservation grabbed me most of all, probably because so much of the city was threatened by demolition and I was so impressed by the local people I met in the neighborhoods fighting to save their communities and the things that made them special. Sometimes the battle was to save a building, other times to get a traffic light in front of a school or to prevent a rezoning that would permit an out-of-scale new project to intrude on a neighborhood.

Most of these grassroots warriors did not know the difference between architects H. H. Richardson and Philip Johnson, but they knew what the local church, school, library, or firehouse meant as an anchor to their neighborhood. They saw the row houses and modest apartment houses dating from the lost eras of quality and care being replaced by dreary, barrackslike structures or excessive scale, projects that undermined the fragile economic and social ecosystem on which any community rests. They knew what inappropriate new development could do. Planners, city officials, academics, and other experts either dismissed or ignored the common wisdom. Worse, many of them didn’t even know how to hear it.

At the same time, some grassroots community rebuilding efforts were mobilizing to reclaim solid but abandoned buildings, trying to create affordable housing for people being displaced by demolition-style rebuilding all over the city. These efforts grew into the significant community-based redevelopment efforts that laid the groundwork for the renewed city, an observable truth ignored or minimized by most contemporary histories of the city. The Cooper Square Committee on the Lower East Side. The People’s Firehouse. UHAB (Urban Homesteading Assistance Board) on the Upper West Side. The People’s Development Corporation and Banana Kelly in the South Bronx. Bedford-Stuyvesant Restoration in Brooklyn.

These groups didn’t oppose development; there was no development to oppose. They created community-based housing organizations and renovated eighty thousand units, setting the stage for the private investment that followed. Collectively, they pushed for changes in the insurance laws that did more to discourage landlord-sponsored arson than any public policies. They developed new ways to finance the rehabilitation of housing, pushed for tenant protection, devised preservation strategies, and developed new and renovated units all over the city that helped stem the tide of abandonment and pave the way for new investment. Over the years, they advanced more redevelopment than for-profit developers did. “More importantly,” notes Ron Shiffman, former director of the Pratt Center for Community Development and longtime adviser to many community efforts around the city, “they have enabled many places to retain their genetic footprint, the form that gave the distinctiveness and unique character to that particular community. They helped spawn the environmental justice and industrial retention movements. And they spurred greater attention to sustainable planning practices and green building approachers.”

I watched these citizen-based efforts rebuild a city in ways officials despaired to understand. To this day, too many “experts” and public leaders fail to recognize the continued validity of this process, in New York City or elsewhere. These citizens all resisted official plans reflecting how experts said things

should

work and how people

should

live but not reflecting how people actually lived or that added to the vibrancy of urban life. These citizen groups were planning from the bottom up, and step by small step they were slowly adding up to big change. I was fascinated by these groups, and I learned from them. I didn’t appreciate then that I was witnessing the precursors of the regeneration of the larger city.

The only way to understand any city or any part of it is to walk the streets, talk to people who live and work in the neighborhoods, look at what works or doesn’t work, and ask why, how, who. Direct observation, not theory. Instinct over expertise. That is the journalist’s habit or should be. It was not the habit of many professionals who claim to know best the interests of the city.

THE 1960S

In many ways, the city in the 1960s and 1970s seemed no different from the New York of my childhood. But in so many ways it

was

different. The World Trade Center and Battery Park City were not yet built. Lincoln Center was in construction. The Metropolitan Opera and the McKim, Mead, and White Pennsylvania Station still stood. The New York City Landmarks Law—one of the earliest in the country—did not exist.

New York Magazine

was yet to be born, first as a supplement to the

Herald Tribune

. Passenger liners graced West Side piers. The Twentieth Century Limited still went from Grand Central to Chicago. Yankee Stadium had not been renovated the first time, and Shea Stadium was in construction.

Suburban malls had not yet made an impact. All the department stores were in their rightful places along Fifth Avenue—Bonwit-Teller, Bergdorf-Goodman, Saks, Lord & Taylor, Best & Co. Fifth Avenue was “the Avenue,” and Thirty-fourth Street was still the preeminent “pedestrian” shopping street. B. Altman’s was at the Fifth Avenue end of Thirty-fourth, Macy’s and Gimbels at the Sixth Avenue end. Ohrbach’s was in between, along with dozens of small shops, both chains and locals. Soon, malls would vacuum the heart out of many American Main Streets. But while malls killed much of downtown America, they only partially injured New York City. The density of this city guaranteed a less dramatic impact than the shell shocks that crippled so many other cities.

On Forty-second Street, stores sold foreign newspapers, hats, costumes, and a great variety of entertainment-related goods. The sparkling marquees of great first-run movie houses were lined up one after another along that still quintessential street. A mix of low-end entertainment outlets, holdovers from the 1920s, gave the street its seedy feel. A few grind houses could be visited. Hubert’s Museum, a Coney Island-style sideshow, had a flea circus, snake charmer, belly dancer, and wild man of Borneo. The pornography was soft core with hard core soon to come in the late 1960s. As newspaper exposés revealed, disreputable property owners welcomed the degenerate uses as tenants to strengthen their push for a publicly funded city renewal scheme and generous bailouts that would handsomely enrich them. Contrived or accelerated deterioration has long been a property owner’s excuse for seeking financial concessions from the city. This pattern was common elsewhere in the city but most glaringly at the time on Forty-second Street.

Beneath its glittering gaudiness, the Times Square district overflowed with great original musicals (

Fiddler on the Roof

,

Funny Girl

,

Cabaret

,

Hello, Dolly

) and dramas (

Golden Boy

,

Tiny Alice

,

The Subject Was Roses

). The regal Astor Hotel had not yet been replaced by a die-stamped, glass-walled office tower. The Astor replacement was the first of many similarly banal ones that followed.

Until the bulldozer of urban renewal and misguided city-planning policies took their toll, the city’s neighborhoods often had their own thriving entertainment centers with at least one movie house, local restaurants, and neighborhood retail to keep many residents happy. Times Square, Broadway theater, and Manhattan nightspots were for the Big Nights on the town and first-run films. By the 1970s, little of that was left, and the days were numbered for what remained. Times Square was New York’s epicenter, and even that was in decline, and not an entirely natural decline at that.

The Upper West Side was like the set for the long-running musical

West Side Story

(opened in 1957), and years away from becoming chic.

4

Run-down brownstones, their high quality intact, lined the side streets. Neglected but elegant apartment towers dominated Central Park West. I loved my first one-bedroom apartment in that small building overlooking Central Park, but walking the side streets was something one did quite cautiously. Nighttime crime in the park was a constant.

The Upper East Side was then the enclave of the rich and the famous. And Brooklyn was another world. Visits to Coney Island and relatives were about the limit of my Brooklyn experience until then. When we lived in the Village, my grandfather occasionally came from Brooklyn for Sunday breakfast, bringing pickled herring, white fish, lox, and bagels from Brooklyn’s Avenue J. When I returned to New York as an adult, he would meet me at the Horn & Hardart on Forty-second Street for a Sunday meal. He was intimidated by Manhattan and knew only the one subway stop at Forty-second Street from Brooklyn. The Bronx was out of my consciousness—except for the zoo and Botanical Garden—though I used to visit relatives there too as a child. Queens I hardly knew, and Staten Island I don’t remember even having visited.

THE 1970S

New York hit bottom in the late 1960s and ’70s, and even optimists could not foresee the rebound that has occurred. Crippling events and conditions scarred the decade. Crime, drugs, police corruption, municipal strikes, litter, housing abandonment—anything that could go wrong did. Even a cable on the Brooklyn Bridge snapped in the mid-1970s.

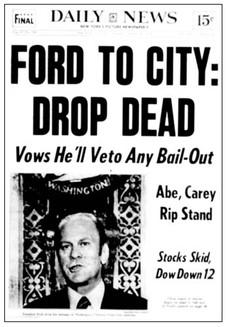

1.3 “Ford to City: Drop Dead” was the

New York Daily News

front page that summed up the state of the city.

New York Daily News

.

The famous headlines are the stuff of legend. “Ford to City: Drop Dead” screamed the front page of the

New York Daily News

on October 30, 1975, when the president refused to help bail out the city’s near bankruptcy. A few days later, he reversed the decision and loaned the city $500 million. In 1979, when Chrysler seemed destined for bankruptcy, the federal government easily extended $1.2 billion in loan guarantees. The same benefit had not been offered ailing New York City. The “fiscal crisis,” as it was appropriately called, had reached the point when the city could no longer sell the bonds it needed to fund its budget. Sympathy from around the country was nonexistent. In the 1970s, New York was probably the most unloved city in the country.

“There it is, ladies and gentlemen, the Bronx is burning,” noted Howard Cosell as he looked up during a game at Yankee Stadium in 1977 and noticed a building on fire. “The Bronx is burning” became the catch-phrase of the day. Arson—both landlord and tenant initiated—was rampant in poor neighborhoods, not just in the Bronx. Few saw a bright future for the city. The South Bronx served as the poster child for the collapse of the country’s inner cities. The worst conditions were visible there. The movie

Fort Apache

, starring Paul Newman, took place in the South Bronx and highlighted the grim reality of uncontrolled crime. That movie wasn’t made until 1981 and kept the worst image alive. Tom Wolf’s

Bonfire of the Vanities

, also set in the Bronx at its worst, was published in 1987. A big hit, it, too, kept the worst images alive.

And then there was a whole year of the serial killer Son of Sam, who preyed on young women and couples, increasing the city’s unease from anxiety to full-blown fear. The media heyday culminated in “CAUGHT,” the

Post’

s dramatic 1977 headline at his capture. And while feeling a sense of relief, the elevated anxiety level of the city did not diminish. Son of Sam seemed to symbolize the crime wave the public feared, a condition common in all American cities in the ’70s. High crime rates depressed everything. Revelations of systematic police corruption did not help public confidence in the era of high crime.