The Battle for Gotham (55 page)

Read The Battle for Gotham Online

Authors: Roberta Brandes Gratz

Tags: #History, #United States, #20th Century

Economist Edward L. Glaeser agrees. “The defining characteristic of Mumbai is not crime or Bollywood, but entrepreneurship even in the city’s slums,” he wrote in the

New York Times

Economix Blog, on May 26, 2009. Dharavi, he noted, “is a place of remarkable economic energy where poor people are managing to eke out a living as entrepreneurs.”

Willets Point is also all about resourcefulness. It looks like sheer chaos but has its own economic rationale. And like Willets Point, the Indian government is preparing to flatten Dharavi and build high-rise towers and business parks, à la Robert Moses, in the mistaken notion that building an economy on real estate instead of entrepreneurship works.

10.6 Rahul and Matias loved the license plate.

Rahul Srivastava

.

On their trip to New York last year, I took Matias and Rahul to Willets Point. They were stunned at the similarities with Dharavi, the big difference being that in Dharavi, people live where they work as well. The same lack of infrastructure exists, as does the creative patching together of small buildings with corrugated tin and other materials. Residents role up their mattresses each morning and get to work.

“Here is a slice of urban life that connected New York to other cities around the world in which raw economic necessity and a tougher set of choices shaped the landscape more than the luxury of planned architectural interventions that is otherwise New York’s signature,” they wrote in a blog report of their visit. “From the outside,” they also observed, “you would never guess the immense ferment going on beneath.”

Effectively, at Willets Point—like Dharavi—over many decades, poor businesses have congregated for mutual support and networking. This is a fundamental and critical component of genuine economic development, in contrast to a publicly subsidized, developer-driven construction project. What evolved on Willets Point is totally self-organized, cannot be “developed” or “planned for,” and is invariably overlooked entirely and undervalued by professionals. Many longtime establishments have been doing very well and serve a low-income community while providing jobs for a mostly Spanish-speaking workforce from nearby Corona. Many workers walk to work. Firms here “provide a wide range of auto-related services, have longstanding linkages with one another, and both compete and cooperate with one another,” noted the Hunter College study.

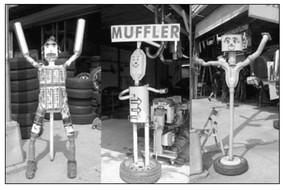

10.7 Artistry and ingenuity not just reserved for cars.

Norman Mintz.

In effect, this is a classic agglomeration, a natural concentration of interrelated businesses that cluster organically to gain strength from proximity to each other. New York’s fur district, jewelry district, garment district, flower district, financial district, gallery district, computer alley, and meatpacking district are all examples of a similar urban economic process. Such agglomerations cannot be relocated. They only happen naturally. Thus, the impact of dispersal would economically weaken the full network and probably some of the individual components fatally.

It is too easy to dismiss the unglamorous existence of scrap-metal yards, auto-body shops, and other messy concerns (41 percent of the total), as happens usually in the press and official descriptions. But this unappealing description masks an assortment of specialized individual auto businesses, including parts, body, glass, tires, muffler, salvage, sales, and one parts supplier specializing in antique cars. There are even brokers who will direct you to the exact business that specializes in your problem. This is a more complex network of businesses than meets the eye, with a wide range of specializations. And, as the Hunter report notes, “auto parts suppliers in the area make access to parts economical and relatively swift.” This is real economic efficiency, the organic urban kind. The report adds: “The relations among the operators of auto-related businesses are often cooperative and mutually supportive, and they form a network that strengthens the attractiveness of the area as a specialized district.”

One anomaly exists at Willets Point that happens to be the largest employer. House of Spices is the largest manufacturer and distributor of Indian foods in the country, with one hundred full-time employees. But there is even more diversity that includes a number of businesses that manufacture or distribute steel products, oil and grease absorbents, utility pipes, safety and surveillance equipment, bakery supplies, and ethnic foods.

Willets Point has served as a classic incubator of new businesses. Many here started small and even with a different business mix. Tully Construction Company, for example, has grown from its 1988 start as a highway contractor into a diverse engineering and construction firm handling a wide range of infrastructure, waste management, and environmental projects in the city.

If one understands the essential, though often hidden, natural process of a vibrant urban economy, one understands why Willets Point businesses are resistant to leaving. Replicating the physical conditions that nourish this increasingly rare and vital network is difficult, if not impossible, as discussed in chapter 6.

Aside from questioning the wisdom of wiping out such an economic concentration, one might also question if the city needs yet another combination of housing, offices, restaurants, shops (i.e., malls), a school, a park, a convention center, and a seven-hundred-room hotel. And, to boot, this is in the flight path of La Guardia Airport! How desirable is it to live under low-flying planes? And because of the highways that encircle the area and serve as barriers now, any new development is going to be auto dependent. One thing is for sure. The city will spend endless public funds now, but the site will remain unbuilt and unproductive until the economy rebounds, or longer. Or the area closest to Citi Field will get force-fed new development to create the pretty face officials want visitors to see.

The bottom line for Willets Point is no different from that for Atlantic Yards and Columbia. This should not be an all-or-nothing Moses-style plan. The wisest strategy, if legitimate urban growth is the goal, would be to install the infrastructure and let the real estate market take care of itself.

First of all, the city’s public investment would be a fraction of the cost of buying out all these landowners at great public cost

and

putting in the infrastructure

and

preparing the site (probably toxic) for a private developer. Current annual tax payments and critical jobs would not be lost in the meantime. Owners could sell and move or stay, as they see fit, and decide what is best for the future of their businesses. What new development would then occur would not be the force-fed kind heavily subsidized by the city; it would be the kind that responds to both local and larger city market demands. Logically, with infrastructure installed, this could be a desirable relocation site for some of the small manufacturing businesses pushed out from other areas of the city where upzonings are taking their toll. “This eagerness to build anew, however, brings with it an impatience to clear away impediments or, as Moses infamously put it, ‘hack your way with a meat ax,’” wrote Karrie Jacobs in a

Metropolis Magazine

Cityside column, “Demolition Man.” She was referring to then Governor Pataki’s willingness to “tear down whatever is in the way” of developers’ plans and to use eminent domain to clear the way. She pointed out how New York is one of the states most willing to use that power meant for a public purpose to advance a private plan.

Clearly, the redevelopment plan is what Jane Jacobs would call a “manicuring job.” The image of the auto-parts store with hubcaps, tires, and decorative items covering the facade is considered an “iconic American image” when embalmed in a Walker Evans photograph (

Cherokee Parts Store—Garage Work

, for one) taken in the South during the Depression. But it is another story when it is real and of today.

As this book goes to press, deals are being struck with the landowners closest to Citi Field, the area of primary official attention. Chances are that land will be rapidly cleared and left empty. At the same time, deals are being struck for businesses, like House of Spices, at the back end of the site to remain, reasonably visually removed from the stadium, or to leave with a generous buyout. How transparent is that?

Lost Precursors

Atlantic Yards, Columbia’s new campus, and Willets Point all exemplify the remaining strength of the Moses legacy and the continuing loss of precursors to urban regeneration. In each case, precursors of regeneration went unrecognized, devalued, and destroyed. City officials may argue, as always is done, that all Willets Point businesses, for example, will be relocated. Assuming that promise is even partially fulfilled, scattering such businesses near and far always destroys the efficacy of their clustering location and diminishes their numbers, productivity, and economic contribution to the city, something New York cannot afford to keep losing.

No chance exists in a Moses strategy to demolish selectively. This was the pattern during Urban Renewal and why I argue the city lost so much more under Robert Moses than is yet understood. The Moses approach still prevails too often, even if fewer homes and businesses are being demolished with each project. The many productive individual initiators visible around the city, whether Jacobs inspired or not, get considerable attention and distract the public from the impact of the Moses-style projects. It can be deceptive, seducing people to believe Jacobs’s precepts prevail.

The fundamental flaw in the Moses approach is its simplicity. It is a formula-based doctrine that oversimplifies what it takes to create enduring places, requires a clean slate, and ascribes no value to what came before. A city is much too complex, too multilayered, too filled with interwoven threads to be sustained by singular, simplistic, self-contained, homogenizing projects. And while many of Moses’s parks and swimming pools were beautifully designed and are much admired today even when totally deteriorated and closed, they are inseparable pieces of a whole Moses vision and strategy that sees the city as a series of physical projects rather than the economic, environmental, historical, social,

and

physical system that it is.

Nor is it correct to say that a Moses is needed to achieve public infrastructure and amenities, since countless cities, including New York, boast similarly important achievements not “done” by him. And many more big ones are currently under construction, as we’ve seen, without a construction czar to move them forward. Not only has this book shown that big things do get done, but it has also shown that many of the projects that don’t get done shouldn’t.

The idea of Moses as a model for implementation is a scary one as well. That, too, has simplicity at its core. Top-down, take-no-prisoners, my-way-or-the-highway—this is no way for things to get done in a democratic city.

And while there may be no point replaying the battles of Moses and Jacobs, I would call on the wisdom of former Salt Lake City planning director Stephen A. Goldsmith, who argued instead that “replaying the lessons learned from those battles will serve the public discourse very well indeed. More importantly, these lessons will advance the ideas Jane Jacobs placed in front of us and hopefully save many places from repeating old mistakes.”

Throughout this book, we have seen where modest-scale initiatives are making big change citywide. Some are citizen initiated; some are initiated by city officials. There is nothing simple about any of them, other than that they work. They reflect Jacobs’s principles even though initiated by people who may never have heard of her. The authentic city changes and grows slowly; it resists acceleration. Authenticity is the common thread of the stories in this book.

Gregory O’Connell’s innovative development in Red Hook, David Sweeney’s rescue and rehabilitation of former factories for new industrial start-ups and small manufactures, Janette Sadik-Khan’s transformation of the streets of the city, Eddie Bautista’s leadership in transforming how the city disposes of solid waste, the citywide landmark preservation movement’s impact on both designated landmarks and undesignated but recyclable buildings and resultant revitalization spur—all is vintage Jane,

all

big change in small incremental steps.