The Battle for Gotham (20 page)

Read The Battle for Gotham Online

Authors: Roberta Brandes Gratz

Tags: #History, #United States, #20th Century

THE WEST VILLAGE

While NYU clearly dominates the east side of Greenwich Village, it has had no visible impact on the West Village. Cross Sixth Avenue and you feel transplanted back into the historical Village of small stores, one-of-a-kind boutiques, walk-up apartments, restaurants, cafés, and unpredictable happenings. The West Village, with its textbook array of historic architecture, misses the aesthetic unity of scores of the city’s historic residential and industrial districts. It does, however, have a different sort of unity. Here, the art of architecture is found in the treasured old, not the fashionable new. Housing costs have skyrocketed, but the resident population remains diverse in all ways. The content of the diversity is not the same—no longshoremen, more blacks—but varied nonetheless.

“The West Village has done very well,” Jane observed on a visit in 2004. “If other city neighborhoods had done as well there would not be as much trouble in many cities. There are too few neighborhoods as successful right now so that the supply doesn’t nearly meet the demand. So they are just gentrifying in the most ridiculous way. They are crowding out everybody except people with exorbitant amounts of money, which is a symptom that demand for such a neighborhood outstrips the supply by far.”

One of the most interesting sites is right on the corner of Sixth Avenue and Third Street. Until 1927 Sixth Avenue ran from Central Park West to a short distance north of here at Carmine Street. In that year, the city blasted away tenements to continue Sixth Avenue south. A few little wedge-shaped pieces of empty space remained, such as a small asphalt lot enclosed by a chain-link fence with several handball and basketball courts that daily host some of the most serious competitions in the city. Not just anyone gets to play there, and sport scouts reportedly come by looking for talent. This is one of those serendipitous urban activities that spring up where space just allows it to happen—never organized, never formalized, but eventually institutionalized in its own urban way. A busy subway entrance sits on this corner. I pass there frequently, but I never go by that a large crowd is not gathered to watch.

Throughout the West Village, small change continues to unfold but sometimes with large impacts. The stretch of Bleecker Street west of Seventh Avenue, during the recent economic boom, was transformed into chic and upscale retail. It has long been fashionable, but somehow the presence of national retailers seems to many people to be more dramatic. But nothing has been torn down to make this happen, and the talked-about transformation may be more of a perception than a reality. The large retail chains can’t dominate. Landmarks and zoning limits deny demolition of walls between buildings for expansion of the ground floor to create the huge spaces that supersize national chains require. Most important, when each phase passes, as it inevitably does, the historic fabric will house the next wave of retail chic that is always looking for modest, affordable street-level space. Natural urban shifts unfold this way.

For the most part, small businesses—particularly family-owned ones—do well there because the tiny store sizes work well for them and because Village residents are especially appreciative of the convenience of having them and can be very loyal customers.

EIGHTH STREET

Bleecker Street has long been the most interesting and probably best-known commercial street, but Eighth Street, from Sixth Avenue to Fifth Avenue, was the location for more of life’s essentials when I was growing up: the grocery store, pharmacy, delicatessen, butcher, and my father’s dry-cleaning store. Comfortably mixed in was a second-generation family-owned jeweler, a leather crafter of citywide renown, a jewelry designer, and an art store. Eighth Street was a center as well of Village artistic and intellectual life. The Washington Square Book Shop was a literary beacon. The Eighth Street Playhouse staged cutting-edge plays and later became an art-film house. The Whitney Museum was founded on this street in 1931 and stayed until it moved uptown in 1948. The Studio School with Hans Hoffmann at the helm was also an important art center. Many artists lived above the stores along Eighth Street or nearby. The street was the epicenter for the New York School of artists in the 1950s.

By the 1960s, drugs and fast-paced tourism took their toll. By the 1970s, most of the individually owned stores and cultural sites had closed, and the local character was completely gone. Eighth Street continued to get worse. Cheap shoe stores, head shops, and low-end clothing invaded like locusts and endured right up to the turn of the new century. The Eighth Street Playhouse, its facade gone, is now a cheap dollar store.

A few good things have occurred, however, and indications point to a slow but sure turnaround, especially with new restaurants opening. Barnes & Noble replaced Nathan’s fast-food hot-dog chain. A few years ago, a merchant group organized a business improvement district. Store upgrades are concentrated on the east side of Fifth Avenue. But west of Fifth, the sidewalk is widened, traffic is calmed, new historic-style lampposts are installed, and various events promote the positive qualities of the street. The balance between pedestrian and car is better, and people feel less pushed aside. A Belgian sandwich shop with fresh baguettes, pastries, and coffee opened on the west corner of Fifth Avenue, the first new sign that upgrading is moving westward. An upscale restaurant opened next door to my father’s former store. Other new and better uses are sure to follow. Ironically, the current economic collapse has shuttered many more of the cheap shoe stores, leaving several vacancies. What will replace them when the economy turns around will be interesting to see.

For me, the Village has mostly been defined by the geography of my own experience growing up there and then attending NYU. And while Washington Square Park is central to all of it and NYU is the overarching presence, the Village is really an assortment of very distinct enclaves with a history and character different from each other.

As Jane Jacobs observed about Greenwich Village years ago in conversation, “It is not small. In fact, it is a pretty big district. Parts were always considered better than others and all different. The South Village was heavily Italian and before that I guess mainly Irish. That area was considered bad. Sullivan Street is considered very chic now, but I remember when it was just teeming with poor children and tenements, so I suppose it was considered bad.”

Jacobs had moved to the Village with her sister in 1934, selecting it because “she found so many people walking in such a purposeful way and so many interesting stores and activities to observe.” This iconic neighborhood became the incubator for her ideas. It was a study area, a laboratory. She observed the different elements that added up to vibrancy in city life. She recognized the same characteristics in other vibrant neighborhoods, large and small, and assembled them into a web of related precepts. “Of course, the West Village where I lived was considered bad,” Jacobs said. “We didn’t know it when we moved here, fortunately, but it had been designated a slum to be cleared first way back in the 1930s when Rexford Tugwell, who would become one of Roosevelt’s ‘brain trusters,’ was chairman of the Planning Commission.” But one official’s slum can be someone’s definition of a good neighborhood to live in. And the Village has always drawn a place-proud population.

WEST VILLAGE HOUSES: KNOWN AS THE JANE JACOBS HOUSES

Parallel to the Hudson along the West Side Highway and a few blocks inland are the West Village Houses built in the mid-1970s. This complex could serve as a national model of everything that was wrong in postwar development policies and everything that is right when community sensibilities prevail. A community fight there defeated the Robert Moses Urban Renewal Plan—apparently, the first defeat nationwide of an urban renewal plan—that would have wiped out the entire fourteen square blocks of historic urban fabric filled with owner-occupied, well-maintained one-and two-family houses, tenements, and individual buildings. All had been restored with private money. But it was designated a “slum,” a necessary official step to qualify for urban renewal money. Residents and businesses in the area knew it wasn’t a slum. They thought well enough of the area, in fact, even with its service and physical limitations, to remain there, open businesses, and invest money. “The people in the Village had watched urban renewal around the city with its waste and profiteering vandalism,” Jacobs recalled.

So much land was being taken, and so much was being lost. The West Village people understood the negative impact all these plans were having on the city.

The sin of the Village was that it had all these mixed uses. All the manufacturing buildings were to be demolished and replaced with high-rises. There would be a little enclave left of all the most expensive and aesthetically appealing houses. The rest would go. Now all those former manufacturing buildings are turned into the most expensive lofts in the city. These people, even the real estate experts, they didn’t know from nothing. They were so ignorant, not just about what they were destroying but what people would like.

The term

slum

is very subjective, differing according to who is using it. Poor conditions in an area may be due more to a lack of municipal services than anything else, as we will see throughout this book. A few buildings may be in need of repair or even in danger of imminent collapse. Some may be fire hazards, or abandoned and run-down. None of these individual conditions should qualify an entire area as a slum, especially when renovation and new infill options have not been explored. More than anything else, the terms

slum

or

blight

reflect the motivation of the people using them.

6

All of this was clear in the fight against the West Village Urban Renewal Plan.

A survey of the area, for example, revealed the presence of 1,765 residents, including 710 families, plus warehouses, truck depots, and mom-and-pop businesses. More than 80 businesses employed hundreds of people. In fact, this designation of “slum” was not too different from the designation applied to many other city neighborhoods declared “blighted” and cleared by Moses in the name of slum clearance. “We took Lester Eisner, regional administrator for the Federal Housing and Home Finance Agency, on a tour so he would learn what the community was really made of,” recalled Jacobs, who led the resistance.

7

“It convinced him this was not a slum. He was floored, couldn’t believe the great range of incomes. He said it was wonderful. But this is the secret he told us: Never tell anyone what you would like. As soon as you do, you will be judged a participating citizen. You’re hooked, trapped. They can ignore you. Eisner alerted us to this. People in New York never knew why we were only so negative. Wagner eventually decided the urban slum designation had to be lifted.”

One of the brilliant things about Jane but little acknowledged was that she believed in and followed smart tactics that she often learned from observing others. She came across as very confrontational and anticompromise, all of which had a purpose. But in this anecdote she reveals that the lesson learned from Eisner was to resist saying what you want until what you don’t want is defeated. Jacobs also believed that it was vital to cultivate your own constituency instead of trying to persuade opponents.

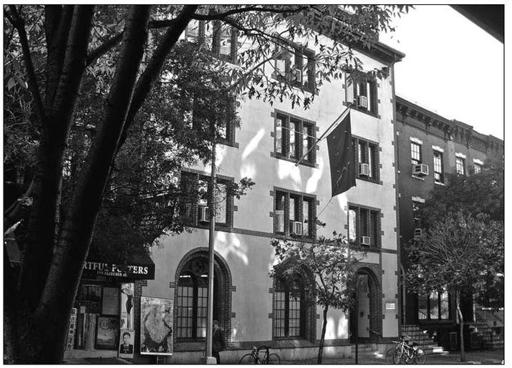

3.2 The Little Red Schoolhouse on Bleecker Street with the expansion into the smaller brick building next door. My elementary school and still a great one.

After the defeat of the Moses Urban Renewal Plan, the successful citizens group the West Village Committee, led by Jacobs, hired its own architect and promulgated its own plan and design for new housing. A basic, modest-scale apartment-house configuration was designed to flexibly fill in the district’s vacant lots, avoiding any demolition or displacement. “Not a single person—not a single sparrow—shall be displaced” was their slogan. The result is an assortment of plain redbrick five- and six-story walk-up apartment houses of different shapes and sizes and three different layouts with an occasional corner store on the ground floor.

8

The planning establishment hated this proposal because it was initiated by the community and left intact the organically evolved mixture of residential and commercial uses. “We hired Perkins and Will, not a New York City firm, so they wouldn’t be blackballed for working with us as all city architects feared,” Jacobs explained. “The West Village Committee was totally self-organized. Anything self-organized is inimical to planners who want control. The city was furious. We had an informant in the Planning Office who told us what was said: ‘If we let this neighborhood plan for itself, all will want to do it too.’ Planners always pick control over spontaneity. If one believes things can happen spontaneously and work well, it diminishes the importance of planners.”

City officials, especially then housing and development administrator Roger Starr, did everything possible to strip the design of appealing amenities. He succeeded, nibbling away at the design in every little way possible. It was twelve years of delays. Costs escalated. The result is bare-bones architecture. Yet a waiting list of potential renters existed from the day it opened. Architecture critic Michael Sorkin has written, “West Village Houses fits unobtrusively within the intimate weave of its surroundings. It’s a model piece of urbanism because of this careful integration; because its architectural expression is not treated as a big, determining deal; and because it grew out of the self-organizing impetus to provide new and better housing for people of modest means for whom the market had little empathy.”