The Bang-Bang Club (30 page)

Read The Bang-Bang Club Online

Authors: Greg Marinovich

Below:

An Afghan man carries his fatally wounded son into the hospital in Kabul after an artillery attack on their residential neighbourhood, 1994. (Joao Silva)

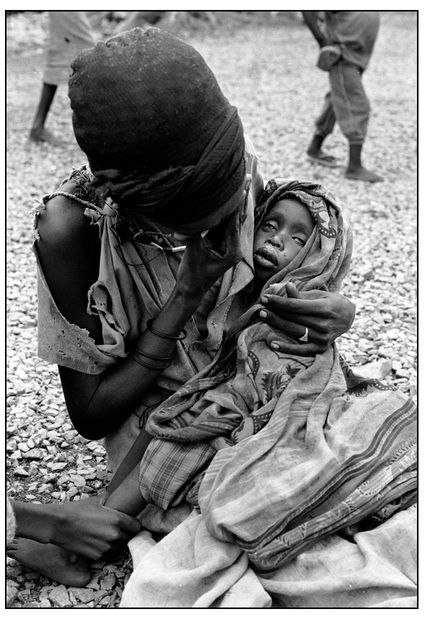

Right:

A Somali woman weeps as her child dies in her arms at an NGO centre in the town of Baidoa where thousands died of a war-induced famine in 1992. (Joao Silva)

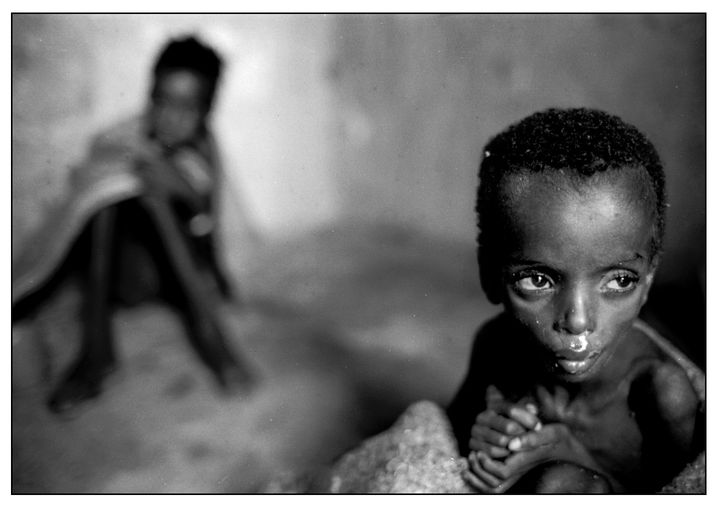

Below:

A starving and ill Somali child waits to die in an NGO centre in Baidoa. This room was for children who were too far gone for the aid workers to waste precious food and medicines on them. (Greg Marinovich)

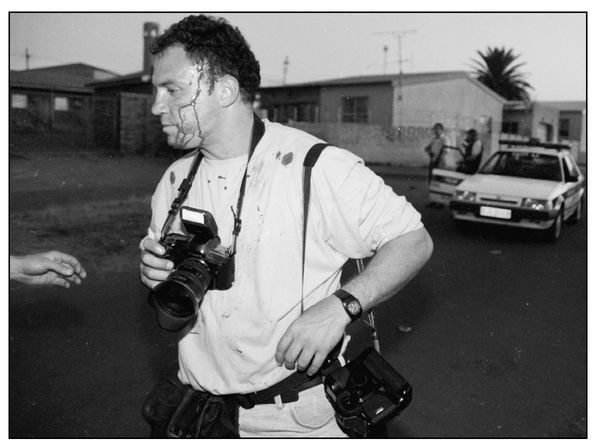

A colleague reaches to assist Greg Marinovich, wounded by police during confrontations between police and ‘coloured’ residents of Westbury, Johannesburg, who were protesting alleged discrimination by the newly elected majority black government, September 1994. (Joao Silva)

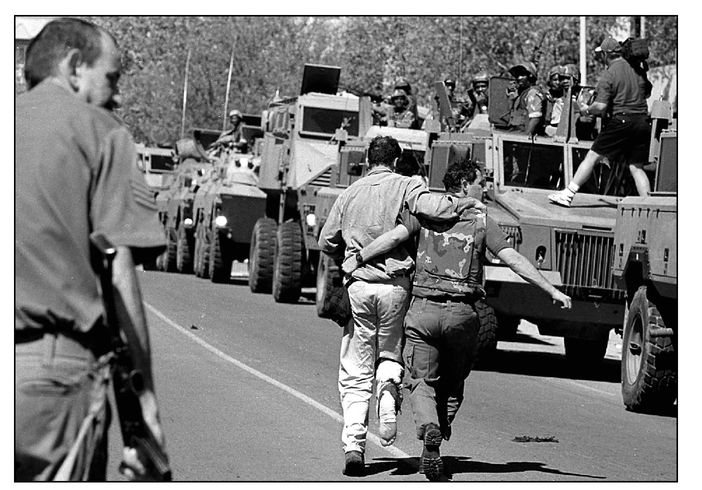

Greg Marinovich being assisted to a South African armoured vehicle after being shot in Lesotho, September 1998, when the South African forces went in to quell a coup, and met stiff resistance from BaSotho troops. (Joao Silva)

After two further operations I was finally able to move out of intensive care. The crisis to survive was over and I began to fret about missing the most important story of my life: Inkatha’s final inclusion in the electoral process, which required the last-minute application of stickers bearing the beaming face of Inkatha’s leader Mangosuthu Buthelezi and the Inkatha symbol on to the bottom of the lengthy ballot papers, a reminder of how close we had been to civil war. Inkatha’s participation had at length been secured by means of gerrymandering in their Zulu heartland, which would ensure them a majority there. It was a small price to pay to avert disaster, but the deal did not please those right-wing whites and security force elements who had thought that they could use Inkatha as part of their strategy to preserve white power. Every day, explosions reverberated through the Reef cities, a last attempt by the right-wing to derail the elections.

Every afternoon and evening my ward was a meeting place for dozens of photographers, journalists and friends. People started bringing food. When Joao and the others came to visit after a day in the townships, they would always find a crowd already there. It was like a subdued party to celebrate that we were still alive and to forget the sad times which surrounded us, if only for a while. Late one night I was already asleep when Ingrid Formaneck and Cynde Strand from CNN crept in, wearing blonde big-hair wigs. Soon we were giggling and laughing, and the night-sister, having taken one look at us, retreated without a word to her station.

One day Kevin visited. His face was mobile and his eyes would not meet mine for more than an instant. ‘I’ve got your cameras - I’ve borrowed them.’ I said fine, but I was surprised. I could not understand why he was acting so strangely - our friendship was such that he knew that I would have lent him the equipment without hesitation, as he would have lent me whatever I needed. Perhaps he had been in a rush when he told me, but he must have known how upset I was at not being able to shoot the elections I had waited so many years for - what it meant to me to be stuck in hospital while everyone else was out

shooting pictures. And here he was, taking the cameras I should have been using, without even a word of consideration. It was unusually insensitive of Kevin. I was also puzzled by the fact that he did not visit me as often as the others. Deep down, I had the feeling Kevin was avoiding me, but I couldn’t understand why.

shooting pictures. And here he was, taking the cameras I should have been using, without even a word of consideration. It was unusually insensitive of Kevin. I was also puzzled by the fact that he did not visit me as often as the others. Deep down, I had the feeling Kevin was avoiding me, but I couldn’t understand why.

In that period Kevin was confused and angry. In the space of just two weeks, he had been arrested for drunken driving, kicked out by his girlfriend, lost his job, won a Pulitzer, been reinstated in his job, only to have his best friend killed. Kevin - and the rest of us - were convinced that Reuters had only rehired him because of the Pulitzer. This was not Reuters’ version of events, but Kevin was deeply angry with them and the relationship was clearly poisoned. I suggested he try the AP and they readily agreed to take his pictures, even though his name was at that time associated with Reuters - the wire constantly needed to be fed pictures. So, just a few days before the election, Kevin resigned from Reuters, and did a couple of freelance jobs for the AP, but then Mikey got him a more regular gig with the French wire service Agence France Presse, and so it was for AFP that he covered the election.

But Kevin was struggling with more than just employment. I heard that he had started saying, ‘It should have been me instead of Ken who took the bullet,’ though he never said anything of the kind to me. In front of me, he seemed to be the least affected by Ken’s death, which was strange, as I knew that Kevin loved Ken like a twin brother. I knew too that he was a dramatic person, capable of intense emotion and of showing it.

I later understood Kevin’s distancing himself from me as a strange form of envy. To have suffered Ken’s fate would have been Kevin’s first choice. Apparently, Kevin constantly talked about getting killed during that time - he did not want to be shot and wounded; he wanted to be killed. He wanted to take the bullet that had killed his best friend. He resented me as I had won second prize. I was there and I took the second bullet, but had survived, so I had a special bond with Ken that nobody else could match.

27 April 1994: Election Day

Before the shooting, I had been planning to spend election day with the Rapoo family. For me, that family was a symbol of courageous people overcoming what had befallen them. They had suffered greatly under the oppressive apartheid system and I wanted to share with them the moment when they voted. But I was in hospital, missing out on what generations of South Africans had been waiting, fighting and even dying for - the first non-racial, fully democratic election. I suggested to Joao that it might be a good idea if he spent the morning with the Rapoo family - the pictures could be really good, at least as good as anywhere else. He immediately understood that I wanted him to be my substitute. I was not sure if he thought it was a good idea for pictures, or if he was doing it for me, knowing how much I wanted to be with the Rapoos. ‘But what if shit goes down?’ he asked, referring to the possibility of violence, thinking about Thokoza. ‘It could go down anywhere,’ I replied, rather disingenuously. He and Gary agreed to go to Soweto for the first day of voting, while Kevin, Jim and the rest decided to go to Thokoza, where the potential for conflict was the highest. But, other than the right-wing bombing campaign, which continued in an attempt to disrupt the election, the level of violence had dropped right off - it had ceased the day after Ken was killed, when Buthelezi had cynically announced that Inkatha would, after all, participate in the election. Responding to the announcement in a press conference, Mandela had said that he hoped Ken would be the last person to die.

Joao and Gary arrived in Meadowlands, Soweto, at dawn, and then joined the Rapoos in their bus as they went to collect people from old age homes. Tarzan had planned to paint the vintage bus that they used to transport fellow church members to services in bright colours for election day, but its notorious gearbox had kept him busy most of the previous week and so they had to collect the pensioners with the bus in its drab sand-coloured paint. These were people who, as youngsters, had experienced the beginning of apartheid and had lived all their adult lives under its shadow - but they had now lived long enough to vote for its demise.

The day had begun hours earlier for the Rapoos. The old man, Boytjie, had had a restless night and got out of bed at four to make himself a pot of tea. While the water was boiling, he heard noises from the street. He went out into the yard and looked through the iron gates. A group of old men in coats were standing in the street. ‘What’s wrong?’ he called, worried that something had happened, that there had again been violence. ‘Nothing’s wrong. We’ve come to queue,’ they told him. The school in the Rapoos’ street was one of the designated polling-stations.

Boytjie invited them in for tea. For all of the old-timers, it was the dawn of the restoration of their civil rights which had been so unequivocally removed by volumes of discriminatory legislation. Thirtynine years before, the police had forcibly moved thousands of these urbanites to the empty veld that would become a part of sprawling Soweto. The matchbox house they were allocated had at first been the symbol of their loss of personal freedom, but in that house, at 1096a Bakwena Street, the cycles of life and death had permeated the very bricks of the house, making it a home. It was in that tiny kitchen, where his family had cooked thousands of meals, that Boytjie had been doused in petrol and awaited a fiery death as he helplessly watched his son Stanley being taken away for execution by hostel Zulus. It was in that kitchen that he had heard the news of his grandson Johannes’s death at the hands of the police. There were many memories to occupy Boytjie and his friends while they silently drank tea. As the break of day approached, the old men put on their heavy woollen coats and joined the lengthening line outside the primary school. The old folk wanted to vote quickly, just in case something happened to upset the miracle.

Tarzan was the next to rouse himself that chilly morning. It was barely five o’clock, but when he went to open the yard he saw a line of people stretching around the block. He rushed back in and shook his wife by the shoulder, ‘Maki, wake up, wake up! You said that since we were next to the school, we’d be first to vote. Have you seen the queue outside?’

This was the day on which decades of disempowerment would fall

away as people made their mark on the ballot - they could finally choose who would govern them. The four years of pain and sacrifice they had experienced living in one of the dead zones - ever since the unbanning of the ANC - had made them even more determined to vote for Nelson Mandela and the ANC. They had watched former State President F.W. de Klerk tour Soweto as his National Party attempted to buy black votes in a frantic campaign circus. But few could forget a half-century of the National Party’s apartheid for a free T-shirt and a boerewors roll.

away as people made their mark on the ballot - they could finally choose who would govern them. The four years of pain and sacrifice they had experienced living in one of the dead zones - ever since the unbanning of the ANC - had made them even more determined to vote for Nelson Mandela and the ANC. They had watched former State President F.W. de Klerk tour Soweto as his National Party attempted to buy black votes in a frantic campaign circus. But few could forget a half-century of the National Party’s apartheid for a free T-shirt and a boerewors roll.

Other books

The King's Marauder by Dewey Lambdin

Double Victory by Cheryl Mullenbach

Doom Star: Book 02 - Bio-Weapon by Vaughn Heppner

Yours in Black Lace by Mia Zachary

One Lucky Hero by Codi Gary

Under the Udala Trees by Chinelo Okparanta

Blue Plate Special by Kate Christensen

Dead South Rising (Book 2): Death Row by Lang, Sean Robert

Web of Lies by Brandilyn Collins

Blackwood Farm by Anne Rice