The Bang-Bang Club (19 page)

Read The Bang-Bang Club Online

Authors: Greg Marinovich

March 1993

Kevin’s eyes could not be misinterpreted when Joao told him that he was prepared to go to Sudan. Kevin wanted to go too, it was his chance to escape the web of problems he felt trapped in.

For Kevin, the war in Sudan - said to be a genocide of the Christian Dinka and Nuer tribes by the Islamic government - was a chance to free himself of his crazy infatuation. So one-sided was the relationship that a desperate love letter he had dropped off at the woman’s house was read out to the guests at a dinner party she was giving, leaving them uncomfortably amused. He also wanted to get off the white pipe. Sudan seemed to present the possibility of making everything right and revitalizing his career, which seemed to have come to a dead-end at the cash-strapped

Weekly Mail

. The newspaper had not been interested in the Sudan trip and insisted he take leave if he wanted to go.

Weekly Mail

. The newspaper had not been interested in the Sudan trip and insisted he take leave if he wanted to go.

Kevin approached various people for whom he had freelanced in the past. Paul Velasco, then owner of the South African photo-agency

SouthLight (now renamed as PictureNet Africa), advanced him some money, as did Denis Farrell at the AP; he also borrowed some from me. Combined with his salary, this was enough to cover the air ticket and hotel accommodation while still meeting his commitments back home.

SouthLight (now renamed as PictureNet Africa), advanced him some money, as did Denis Farrell at the AP; he also borrowed some from me. Combined with his salary, this was enough to cover the air ticket and hotel accommodation while still meeting his commitments back home.

Kevin was on a high, motivated and enthusiastic about the trip. He was on the rebound from his spectacularly unsuccessful relationship when he met Kathy Davidson at a party. A good-looking, intelligent and pleasant school teacher - the perfect antidote to his usual choice of hard-edged women. Kathy found him intriguing and attractive, and let him have her telephone number.

For Joao, the excursion was a chance to expand his career. He was still working at

The Star

when a former photographer, Rob Hadley, who had taken a job with the United Nations’ Operation Lifeline Sudan project, had offered him and Kevin the chance to get into southern Sudan with the rebels. Joao had jumped at the offer, and began making the arrangements.

Newsweek Magazine

had promised money-a guarantee to secure a first look at the pictures. When Joao approached Ken to get leave for the trip, Ken instead secured Joao an assignment from

The Star

’s foreign news service. If his pictures from Sudan were as strong as those from his self-funded trip to Somalia the previous year, it could lead to other assignments with major international magazines. His dream of being a war-photographer beyond the borders of South Africa had begun to materialize.

The Star

when a former photographer, Rob Hadley, who had taken a job with the United Nations’ Operation Lifeline Sudan project, had offered him and Kevin the chance to get into southern Sudan with the rebels. Joao had jumped at the offer, and began making the arrangements.

Newsweek Magazine

had promised money-a guarantee to secure a first look at the pictures. When Joao approached Ken to get leave for the trip, Ken instead secured Joao an assignment from

The Star

’s foreign news service. If his pictures from Sudan were as strong as those from his self-funded trip to Somalia the previous year, it could lead to other assignments with major international magazines. His dream of being a war-photographer beyond the borders of South Africa had begun to materialize.

Fax messages from Rob stressed the latest downturn in Sudan - the major rebel factions had split into tribally based groupings with the result that entire villages had been massacred by opposing tribal militia, and the government had seized the opportunity to launch a massive offensive against the divided rebels. The part of southern Sudan that Joao and Kevin wanted to get to was an especially vulnerable area in the remote hinterland dubbed the ‘the Famine Triangle’ by aid workers.

The Southern tribes of Sudan are Christian or animist and had been grouped together under the rebel umbrella group, the Sudanese People’s Liberation Army (SPLA). They had been fighting for

autonomy from the Khartoum government, which had been dominated by Islamic northerners ever since independence in 1956. The low-key war had been spurred to new intensity in the 80s by the government’s adoption of Islamic Sharia Law. The story which Joao and Kevin hoped to cover was the recent bloody split in the SPLA. Sudan is a notoriously difficult country to work in, with a government that refuses journalists entry to the south, and rebels that are either pressshy or expert at manipulating the prying eyes of outsiders. The breaking and forging of alliances makes it difficult to predict the situation from one week to the next, and aid organizations have great difficulty in getting food aid in with any regularity.

autonomy from the Khartoum government, which had been dominated by Islamic northerners ever since independence in 1956. The low-key war had been spurred to new intensity in the 80s by the government’s adoption of Islamic Sharia Law. The story which Joao and Kevin hoped to cover was the recent bloody split in the SPLA. Sudan is a notoriously difficult country to work in, with a government that refuses journalists entry to the south, and rebels that are either pressshy or expert at manipulating the prying eyes of outsiders. The breaking and forging of alliances makes it difficult to predict the situation from one week to the next, and aid organizations have great difficulty in getting food aid in with any regularity.

Kevin and Joao prepared carefully for the trip. The day before they left for the Kenyan capital of Nairobi - the best transit point for trips to southern Sudan - they met at Kevin’s rented house in the Johannesburg suburb of Troyeville. Kevin’s entire bedroom was covered by numerous packets and bags. Ken had accompanied Kevin on a shopping trip for everything from mosquito nets to dehydrated food - they did not know what they might need. Joao and Kevin sat on the bed, laughing and excited, and shared a joint. Ken was drawn into their excitement, and took a picture, then left them to finish their packing.

The next day, after a five-hour flight north, Kevin and Joao arrived in Nairobi and went to the Parkview Hotel, one of the cheaper, rather dingy, hotels that cater to backpackers and other budget travellers. To economize, they shared a room that enjoyed a view of a muddy alley. The telephone only reached as far as the lethargic receptionist and there was no television.

It was a Sunday in Nairobi and deathly quiet. They went for a walk, Kevin hyper-active, striding and talking fast. They ended up drinking beer on the colonial Oaktree Hotel’s veranda, watching the tropical sun set over the city. Kevin was excited and happy to be in Nairobi, and they were both looking forward to getting to Sudan.

The next day things started going wrong. Kevin tried to change a 100-dollar bill and the bank rejected it - it was a counterfeit. They contacted Rob at the Operation Lifeline Sudan headquarters at Girgiri

on the outskirts of Nairobi, but further disappointment was in store for them. The plan had been that they would fly in on a food drop, and spend about a week on the ground before being picked up on the next food delivery, but an upsurge in fighting meant it was unsafe for the planes to land, and the aid flights had been suspended. Their trip was put on hold - indefinitely.

on the outskirts of Nairobi, but further disappointment was in store for them. The plan had been that they would fly in on a food drop, and spend about a week on the ground before being picked up on the next food delivery, but an upsurge in fighting meant it was unsafe for the planes to land, and the aid flights had been suspended. Their trip was put on hold - indefinitely.

Every day they went out to the UN compound to see if the situation had changed, but for five days they got the same negative answer. The disappointment built up in the tiny hotel room. Joao was furious, unhappy. All his careful planning was going down the toilet. Time passed slowly and painfully; they spent sparingly and ate in increasingly cheap restaurants. They did the rounds of the aid agencies, to see if any of the other organizations were flying in, despite the fighting. They abandoned the more expensive personal taxis and began using matatus - the colourful local minibus taxis which pack in up to 20 passengers. The drivers seemed to be in competition as to who could fit the largest disco speakers in their vehicles. When the buses were very full, the speakers would serve as seats, and on one such crammed trip Kevin had to sit on a speaker. The reggae that blared out of the speaker was too loud for anyone to speak and be heard, so Kevin sat back with an amused look of contentment, and took the occasional picture through the window with his cherished old Leica M3.

In spite of their lack of progress, Kevin was having a good time. All he could talk about was how this trip was going to work out and how everything was going to be great. He made plans to resign from the

Weekly Mail

, go freelance and pursue a relationship with Kathy - get some stability in his life. Joao, on the other hand, was uptight. The pressure was getting to him, he had sold the trip to

The Star

and

Newsweek

on the strength of combat images, and there he was, stuck in Nairobi with little hope of getting near the fighting any time soon.

Weekly Mail

, go freelance and pursue a relationship with Kathy - get some stability in his life. Joao, on the other hand, was uptight. The pressure was getting to him, he had sold the trip to

The Star

and

Newsweek

on the strength of combat images, and there he was, stuck in Nairobi with little hope of getting near the fighting any time soon.

Then suddenly there was a UN trip to Juba-a besieged, government-held town in the south of Sudan. A barge carrying food aid had been travelling up the Nile and had finally made it to Juba. It was an ‘in-and-out’, a one-day affair. Since Kevin had the guarantee from

the AP, the UN put him on the plane flying in. There was no room for Joao, who had to stay behind. He was livid. Joao had done most of the preparatory work, set up the main part of the trip, and Kevin, who had mostly just followed his lead, was getting into Sudan while he cooled his heels. He assumed the worst: this was it - there would be no other chance to get to Sudan and he would return home without having shot a frame.

the AP, the UN put him on the plane flying in. There was no room for Joao, who had to stay behind. He was livid. Joao had done most of the preparatory work, set up the main part of the trip, and Kevin, who had mostly just followed his lead, was getting into Sudan while he cooled his heels. He assumed the worst: this was it - there would be no other chance to get to Sudan and he would return home without having shot a frame.

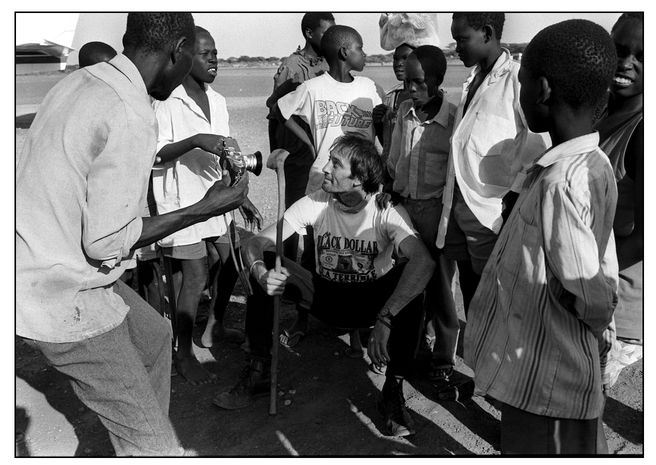

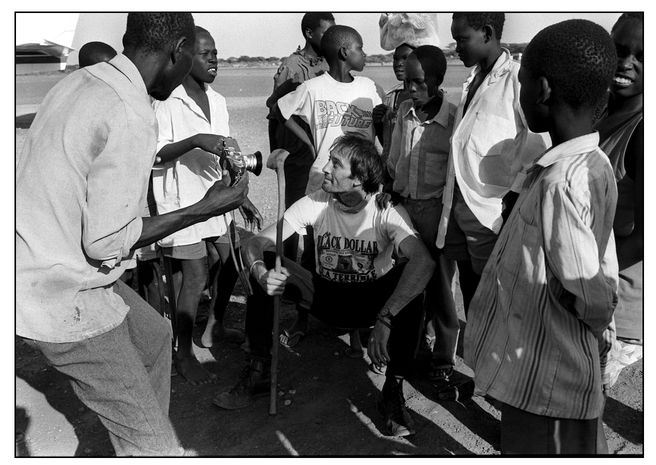

Kevin Carter plays with children as a local villager looks at his camera in the Kenyan border settlement of Lokichokio, March 1993. (Joao Silva)

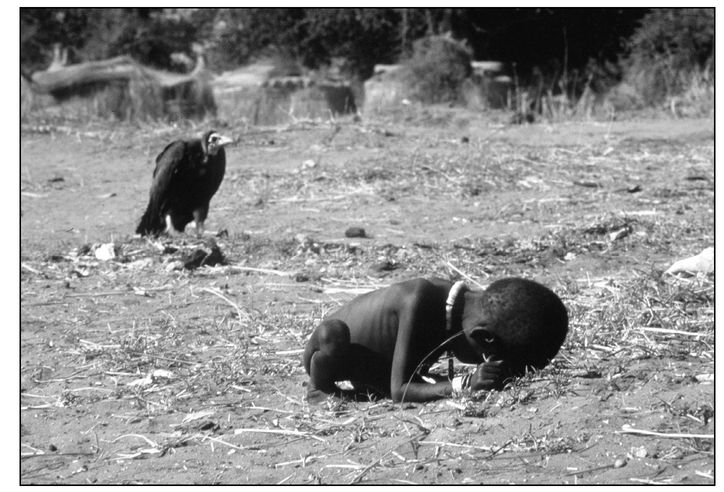

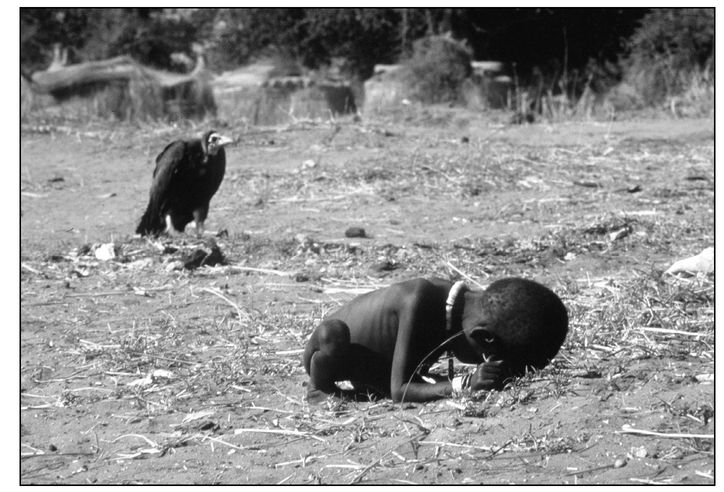

A vulture seems to stalk a starving child in the southern Sudanese hamlet of Ayod, March 1993. This picture would win Kevin Carter the Pulitzer Prize for Feature Photography. (Kevin Carter/Corbis Sygma)

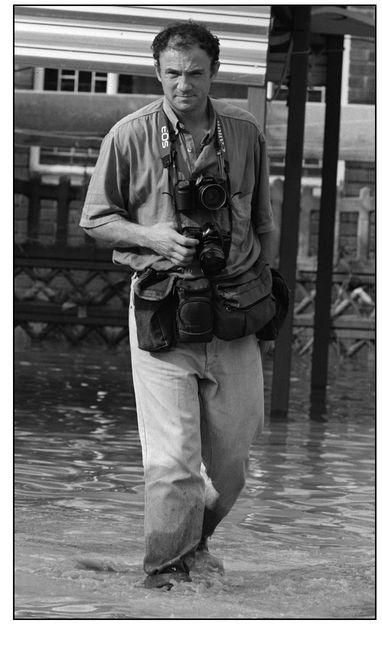

Left:

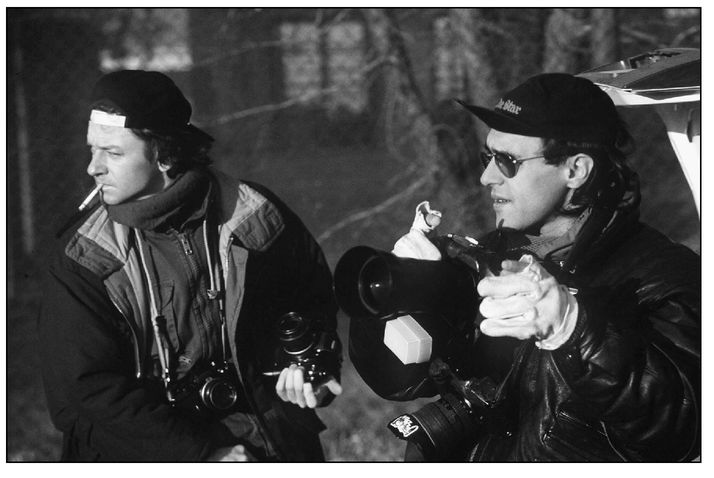

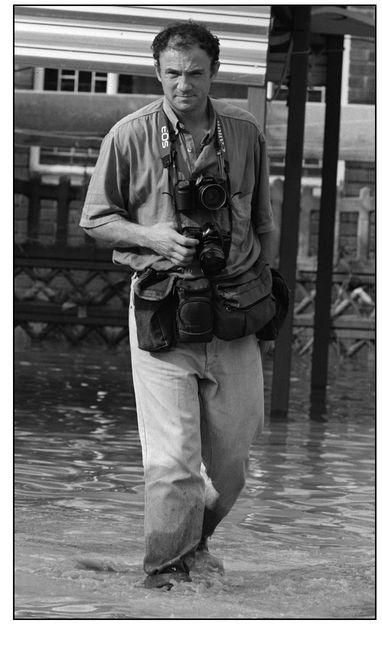

Greg Marinovich covering floods in the Kwa-Zulu Natal town of Ladysmith, 1996, shortly before he left to take up a post in Jerusalem for the Associated Press. (Joao Silva)

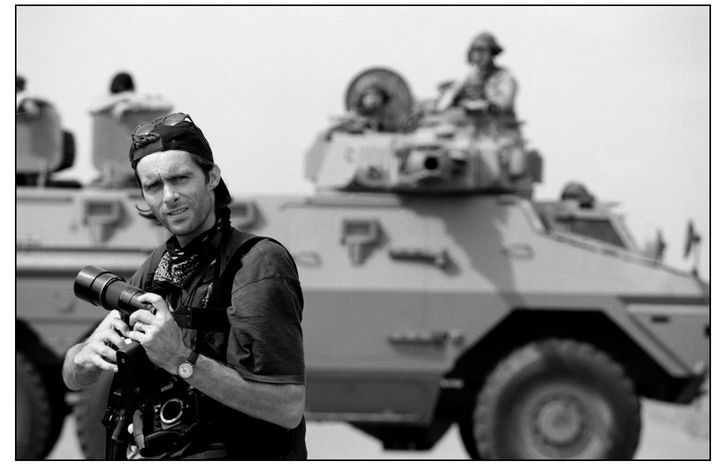

Below:

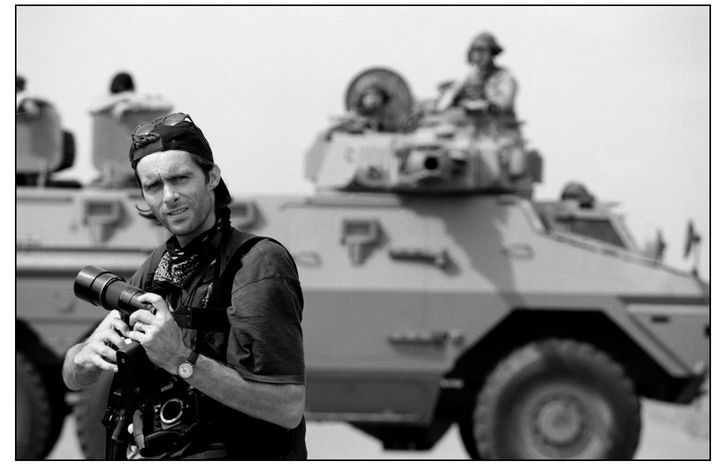

Ken Oosterbroek, with a South African Defence Force armoured vehicle behind him, during the fall of the homeland of Ciskei, February 1994. (Joao Silva)

Right:

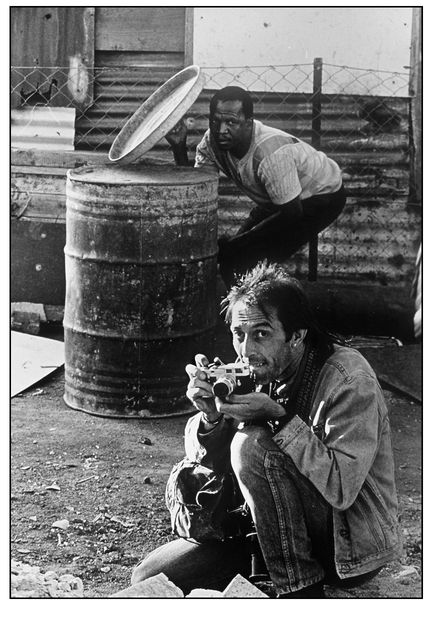

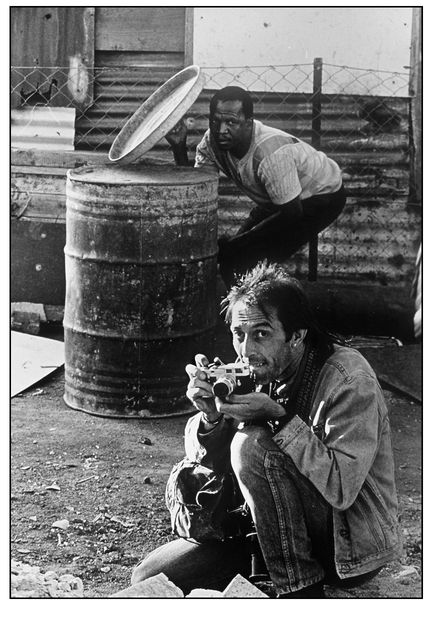

Kevin Carter crouches while covering clashes between the ANC and Inkatha in Alexandra township, Johannesburg. (Guy Adams)

Below:

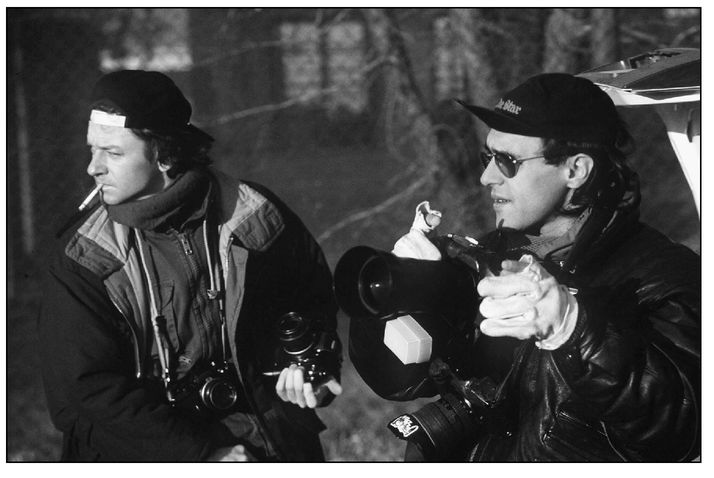

Gary Bernard, left, and Joao Silva on a winter morning in Soweto township, July 1994. (Greg Marinovich)

Three dead men lie in the street where they were gunned down during a battle between Inkatha and the ANC in Soweto’s Dobsonville suburb. The graffiti reads ‘Remember - Life owes you

nothing

- you owe everything to life!!!’ (Joao Silva)

nothing

- you owe everything to life!!!’ (Joao Silva)

Policemen load corpses into an open trailer after a night’s violence between ANC and IFP supporters in Thokoza, July 1993. Sixty people were killed in the township that weekend. (Joao Silva)

An Inkatha supporter lies dead amongst his traditional Zulu weapons after several hundred warriors tried to storm the ANC’s headquarters, Shell House, during a march in downtown Johannesburg, 1994. Several Zulus were killed, and it became known as the Shell House Massacre. (Greg Marinovich)

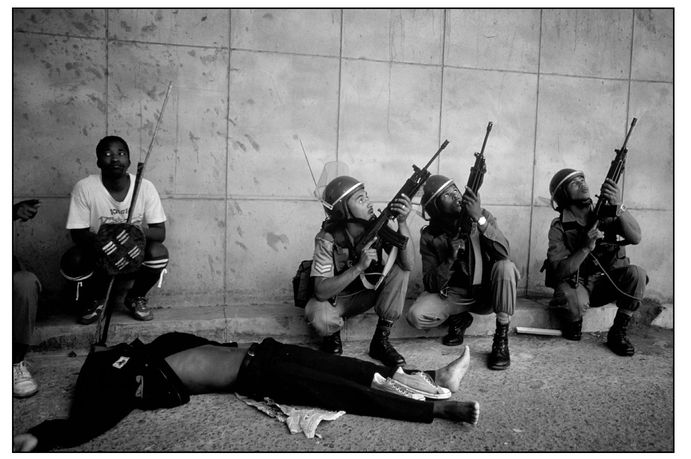

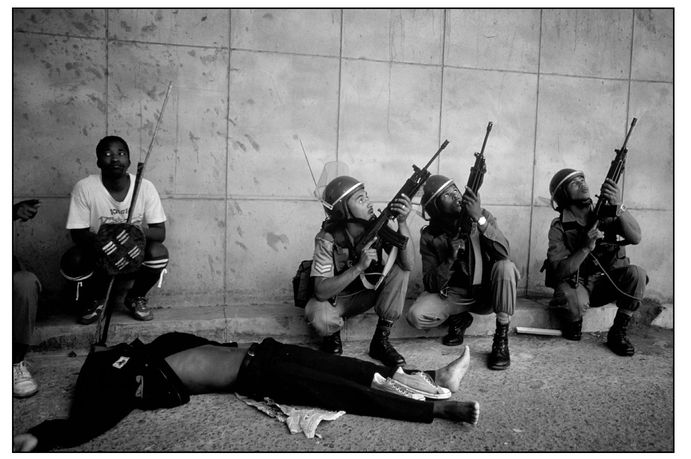

Another Inkatha supporter lies dead, with his shoes taken off for his journey to the next world, as soldiers look for the sniper who killed him during the Shell House Massacre. (Greg Marinovich)

Kevin Carter during a late night shift as disk jockey at the Johannesburg station, Radio 702. (Joao Silva)

Other books

Heels and Heroes by Tiffany Allee

The Fury Out of Time by Biggle Jr., Lloyd

Prince of Shadows: A Novel of Romeo and Juliet by Caine, Rachel

Hellion (Seven Brides for Seven Bastards, 7) by Jayne Fresina

A Decadent Way to Die by G.A. McKevett

A Reason to Believe by Governor Deval Patrick

The Heirs of Owain Glyndwr by Peter Murphy

Boelik by Amy Lehigh

My Misspent Youth by Meghan Daum

The Changeling by Christopher Shields