The Ball (24 page)

Authors: John Fox

What is, therefore, in the English game a matter of considerable chance is “cut-and-dried” in the American game; and the element of chance being eliminated, opportunity is given for the display in the latter game of far more skill in the development of brilliant plays and carefully planned manoeuvres.

Camp was a pragmatist and knew all too well that the new rule would be meaningless if it wasn't enforcedâif there wasn't a stiff penalty for breaking it. The line of scrimmage secured a firm hold the following year when the rules committee assigned an “offside” penalty for crossing it too early. The first or second time a team was offside, the snap would be replayed. If it occurred a third time, possession would turn over to the other team.

Of course, the danger of Camp and the IFA making the rules up as they went along is that each rule change brought with it unforeseen, and often unwelcome, consequences. While the scrimmage provided for possession of the ball, it failed to address the question of its surrender. Major problems with the new rule became clear when Princeton and Yale met in 1880 for a much anticipated matchup in two inches of wet snow at New York's Polo Grounds. As described by Parke Davis, the second half began with the Yale offense aggressively pressuring Princeton's goal. That's when Princeton's too-clever captain, seizing upon a loophole in the new rules, ordered his players to just hold the ballâno kicking, no passing. Princeton held possession for nearly the entire second half and the game ended with no score and 4,000 freezing cold and sorely disappointed spectators.

The “block game,” as this strategy was called, resulted in the most excruciating games in football history. One newspaper described the strategy as an “unmitigated evil.” Fans responded to the scoreless, plodding performances by throwing garbage on the field. Camp was as unhappy as anyone with the situation. One of his main complaints about early football had been what he deemed the “cowardly” team play that privileged defensive tactics over a strong offensive attack. The new abuses, he later wrote, “so disgusted spectators that it was absolutely necessary to make a change.”

The change cameânot a moment too soonâin the 1882 rules committee. Camp persuaded his colleagues to adopt a system of “downs” that required the team in possession to advance the ball in a limited number of attemptsâor relinquish possession. “If on three consecutive fairs and downs a team shall not have advanced the ball five yards or lost ten,” read the latest amendment, “they must give up the ball to the other side at the spot where the fourth down was made.” With the system of downs came the need for referees to measure the gain or loss of yardage. Camp then ignited fierce debate with his suggestion that the field be chalked with lines every five yards.

“But the field will look like a gridiron!” exclaimed the Princeton committee representative, E. C. Peace.

“Precisely,” responded Camp, and fields across the country got their familiar battle stripes.

After college, Camp took a job as a clerk at the New Haven Clock Company, a family business, where he worked for years while serving as the unpaid coach of the Yale football team. When his day job made him late for practice, which frequently happened, he'd send his wife Alice ahead to take notes that he'd review at home. Rising in the company to the position of president, Camp applied the familiar order and regimen of the production line to his coaching method and to the game he set about shaping.

As Mark Bernstein has pointed out, it's no coincidence that American football was the first major sport to be played against a clock. When Princeton met Rutgers in that first intercollegiate game, the team that scored six points first won the match. By the 1880s, when the United States first standardized time zones, game periods were being timed and referees were armed with stopwatches. Ever since then, the outcome of game after game has been decided by minutes and seconds. It's impossible now to imagine a football game where time is not the most unforgiving opponent on the field.

Having deftly crafted the chessboard and the rules of engagement, Camp next set about developing the unique capabilities of each piece arranged on it. “Division of labor,” he wrote, “has been so thoroughly and effectively carried out on the football field that a player nowadays must train for a particular position.” The “quarter-back,” he wrote in his groundbreaking manual,

American Football

, is a “position in which a small man can be used to great advantage.” Halfbacks and backs require “dash and fire,” while for the center, or snap-back as it was called, “brain and brawn are here at their highest premium.” In those early days of organized athletics, training was still a novel concept. Players showed up on campus in the fall, fat, tan, and happy, and started playing ball. But soon scientific regimens were introduced and preseason training became standard protocol.

In his manual, Camp dedicated several appendices to evaluating the merits of various training systems and diets. Following the “J. B. O'Reilly” system, for example, an athlete should rise at 7:00

AM

, “get a good dry-rubbing, and then sponge his body with cold water.” His breakfast “need not always consist of a broiled mutton-chop or cutlet,” which, to my taste at least, leaves the door open to a wide array of possibilities. Dinner served at 1:00

PM

was ideal, and “any kind of butcher's meat” with vegetables was fine as long as there was no pastry served. Water was the only drink to be allowed the American athlete, though English athletes were forgiven in this area due to the fact that “the climate and the custom in England favor the drinking of beer or claret.” A light supper at 6:00

PM

was great so long as it didn't “consist of slops or gruel.” The athlete's day should end with lights out at 10:00

PM

in a room with an open window, with a “draught . . . if possible, though not across the bed.”

He even had opinions as to the level of table service required for an athlete in training. When asked by another coach to diagnose a team situation in which several star players were “manifestly out of sorts,” Camp sat down to dinner with them and quickly pinpointed the problem. “The beefâand an excellent roast it was, tooâwas literally served in junks, such as one might throw to a dog.” Some boys were accustomed to a certain level of dining, he asserted, and their appetite and physical condition could suffer from poor table service.

In Camp's vision of football, nothing could be left to the vagaries of chance. And all the fresh air, mutton chops, and fancy flatware paid off. In his eight-year career as head coach, first at Yale and then at Stanford, Camp lost only five games. In 1888, his first year as Yale head coach, the Bulldogs outscored their opponents a staggering 698â0.

With relentless attention to detail, in the smoke-filled huddle of IFA committee meetings, Camp and his fellow rule makers regulated football into existence, converting it in less than a decade from a raucous free-for-all into an obsessively methodical sport. Rules were enacted and put to the test on the field, then brought back to the scrutiny of the committee to be fine-tuned or thrown out. The snap of the scrimmage replaced the scramble of the scrum. Random pasture gave way to the calculated geometry of the gridiron. Time became the most ruthless player on the field, forcing decisiveness and action. Specialization turned the passions of the mob into the precision of the machine, with each man selected and trained to play his part. Plays were called, signals devised, and the quarterback assumed his starring role as “director of the game,” opening a door for the Tom Bradys and Peyton Mannings of the future to step through.

Rule by rule, committee by committee, Camp's grand vision of order unfolded on the gridiron. But as the game became more open, methodical, and scientific, it also, ironically, became more violent. The 1880s saw running games unlike any that have been seen since. In 1884, Wyllys Terry of Yale ran 115 yards for a touchdown against Wesleyan, setting a record that will stand forever thanks to the field being shortened soon after. And in an effort to discourage blocking and prevent neck injuries in what was becoming an increasingly physical game, Camp pushed through a proposal in 1888 to allow tackling below the waist for the first time.

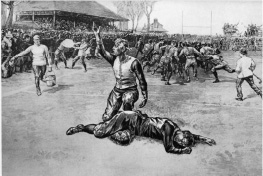

It was Harvard football adviser and avid chess expert Lorin Deland who in 1892 conceived one of the most brutal plays to ever appear on the field. Deland, who had never played football and only witnessed his first game two years earlier, turned to the history booksâand to Napoleon's military tactics in particularâto devise his take-no-prisoners play known as the “flying wedge.” “One of the chief points brought out by the great French general,” Deland noted, “was that if he could mass a large proportion of his troops and throw them against a weak point of the enemy, he could easily defeat that portion, and gaining their rear, create havoc with the rest.”

In the second half of the annual Harvard-Yale game, Deland lined up his squad in a unique V formation stretching 25 yards behind the ball. At the time, there was no requirement at kickoff to kick the ball a certain distance, so the kicker lightly tapped the ball, then scooped it up and ran with it. Nine other players formed a protective wedge around the runner and bore down on one of Yale's weakest defensemen, trampling him to the ground in what was known as a “mass momentum” play. Deland's strategically violent play, described at the time as “half a ton of bone and muscle coming into collision with a man weighing 160 or 170 pounds,” kicked open a hornet's nest of controversy around football that wouldn't subside for another 20 yearsâand has never really gone away. Amos Alonzo Stagg, on his way to becoming a coaching legend at the University of Chicago, called the play “the most spectacular single formation ever.” “It was a play,” wrote a reporter for the

Boston Herald

, “that sent the football men who were spectators into raptures.”

The standard-issue equipment of the time offered victims little protection from the crushing impact of the flying wedge. To protect their heads, players wore only a knit cap, a strap-on nose guard, and, for a brief spell, fashionably long hair. Rubber cleats were tacked onto street shoes, and the earlier canvas “smock” was replaced by tougher moleskin trousers with sewn-in padding. Coaches and players experimented with new forms of protection as the game became more physical. The first padded leather “head harness” appeared in 1896, and patents were filed soon after for variations on the theme, including a pneumatic helmet that borrowed from ball design by encasing the head in a rubber sack inflated with a hand pump. Among Deland's many innovations was a one-piece leather suit that made it harder to grip and tackle his players. One particularly industrious halfback of the era showed up on the field for a championship game greased from shoulder to knee, prompting the creation of a rule that lasted in the books for years that “No sticky or greasy substance shall be used on the persons or clothing of the players.”

As the bloodied bodies of 20-year-old men were dragged off the field, public opinion quickly turned against the game. Rugby had always been a rough, even occasionally brutal sport, and controversy had dogged it from day one. But in the Progressive era of the late 19th century, when muckraking journalists and social activists were busy reforming social ills and political corruption wherever they could find them, football was a ripe target for reform. The game was exploding in popularity on college campuses across the country and becoming as integral to the celebration of Thanksgiving as church and turkey. By the 1890s, an estimated 5,000 games involving 110,000 participants were being played on Thanksgiving in every corner of the United States. The holiday, lamented one writer, “is no longer a solemn festival to God for mercies given. It is a holiday granted by the State and the nation to see a football game.” Weekend games and tailgate parties were already entrenched fixtures of the college experience. And yet, in its “evolved” form, football presented society with an uncomfortable paradox: a game that was more violent in its modern form than it had been before: a game that had been scientifically, if unwittingly, engineered to be more deadly. New training methods made for stronger, bulkier, and more specialized players. New helmets padded their confidence more than their heads as they hit harder, more precisely, and with greater coordination than before. The best coaches devised mass plays like the flying wedge to achieve maximum impact and damage. So much for progress.

A widely read

New York Times

editorial from December 1893 titled “Change the Football Rules: The Rugby Game as Played Now Is a Dangerous Pastime” called for reform, documenting story after story of players who'd been killed on the gridiron. Another

Times

editorial went so far as to compare football to lynching.

The Nation

, amid all the frantic editorial voices, was the game's staunchest critic, calling over and over again for nothing less than its complete abolition. In just one Saturday in November 1893, the magazine reported a host of injuries and deaths, referring to football as a “murderous game”:

Captain Frank Ranken of the Montauk football team had his leg broken in two places . . . Robert Christy of the Wooster University died from a kick in the stomach. . . . At the game at Springfield . . . Mackie punched his head into Stillman's stomach . . . Beard stepped “unconsciously” on Wrightman's head, and Acton hit Beard a smart blow on the chin.