The Ball (14 page)

Authors: John Fox

A Mazatlán businessman and longtime supporter of the game, Jesús Gómez, has taken the lead in the search for an answer, and the Ulama Project's researchers have teamed up with members of the Mazatlán Historical Society to experiment with commercial latex imported from as far away as New York City. “If we can't get natural rubber,” said Gómez, “we need to find another way. Otherwise,

ulama

will not survive. It's that simple.”

So far, though, artificial rubber has failed to replicate the look or feel and, most important, the remarkable bouncing properties of traditional balls. “Look at this,” said Chuy after the game at Los Llanitos. He dropped a lumpy white blob of low-grade latex, the result of Gómez's latest experiments, and watched it bounce erratically off his patio.

“This doesn't work,” he exclaimed with visible disgust. “It's not natural rubber!”

As the owner of the town's lone regulation ball, Gómez suggested, Chuy may have a vested interest in making sure no substitute is found. “Unfortunately, the ball has come to symbolize control of the game.” And for Chuy and his teammates, debates about the ball and the game seem to feed their sense of competition: Who's going to decide the future of

ulama

âthe players who remain or some well-meaning but meddlesome academics and outsiders?

As I expressed my thanks to the players and their families who had hosted me in Los Llanitos and got ready to head back to Mazatlán, Chuy pulled me away from the other visitors and project members and cornered me with his prized ball in hand, determined to have the final word.

“This ball is special. It's made from a process that's thousands of years old.”

He dropped the smooth, heavy mass into my hands. “This ball,” he said, as if holding it were the only way to really understand, “is not of these times.”

The Creator's Game

There are two times of the year that stir the blood:

In the fall, for the hunt, and now for lacrosse.

Oren Lyons Jr., faithkeeper of the Onondaga Nation

I

t's May 22, 2009, at the New England Patriots' stadium in Foxborough, Massachusetts, and another, much older contest has taken over the gridiron: the NCAA lacrosse championship. Two powerhouses, Syracuse and Cornell, have been pushed to “sudden victory” overtime by an improbable fusillade of goals by the Orange in the final minutes of regulation. Cornell wins the face-off and gets it to one of their top scorers. Syracuse defenseman Sid Smith checks him hard, strips him of the ball, and works it quickly down field to his best friend, attack man Cody Jamieson. Jamieson winds up with a left-hand shot so perfect, so routine, that he never had to look back to know it went in.

Having just clinched the championship, Jamieson, a Mohawk Indian, turns and charges 80 yards upfield, stick over his head and a trail of white-and-orange jerseys in jubilant pursuit, to embrace Sid, a Cayuga Indian whom he'd grown up with on the Six Nations of the Grand River Reserve in Ontario.

It was a moment that, by all reasonable odds, should never have taken place. That Syracuse should pull off its 10th NCAA championship win was historic but not surprising. What defied the odds was that an American Indian game banned by early missionaries as “sorcery” should have hung on through four centuries of disease, genocide, and warfare. Lacrosse, which had patiently infiltrated the white culture that nearly extinguished it, had now arrived at the point where it could be played live on ESPN in front of 68,000 fans: this was truly remarkable. Decades after their great-grandfathers had been barred from playing their game, two young men of the Wolf Clan of the Iroquois League shared a victory that, save the efforts of their determined ancestors, could quite easily never have occurred.

But lacrosse is a survivor.

B

y

AD

800

ulama

had worked its way across the Rio Grande, influencing the development of a short-lived rubber ball game in ancient towns throughout Arizona and New Mexico. The long-distance running Tarahumara people played a kick-ball game, called

rarajipari

, across the deserts and canyons of northern Mexico. Shinny, a popular stick-and-ball game similar to women's field hockey, brought women and men out to play in villages from California to Virginia. And many Indian tribes, from the Inuit of Alaska to those encountered by the first Pilgrims, had their own versions of football. The game of

pasuckuakohowog

, played by 17th-century New England tribes, for example, involved hundreds of villagers kicking an inflated bladder across a narrow, mile-long field. It was not all that different, the Pilgrims noted, from their own football.

Few of these games are still played, and some are remembered only by archaeologists and museum curators. Some live on in tribal legend or traditionâpreserved and reenacted but long divorced from their vitality and cultural relevance. Then there's lacrosse, one of the fastest-growing sports in the world.

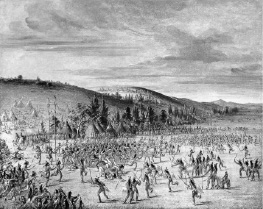

At the time of European colonization, lacrosse was played in one form or another from the western Great Plains to the eastern woodlands and as far south as Georgia and Florida. Despite variation from one region to the next the game was everywhere essentially the same. Teams of up to several hundred men would face off across an open field, often oriented to the cardinal directions, which could stretch for a mile or more in any direction. The only boundaries recognized were natural onesâa rocky outcrop, a stream, a dense stand of trees. Using carved wooden sticks terminating in a pocket made from either wood or woven strips of leather or animal gut, players competed over a stuffed animal-skin ball or one carved from the charred knot of a tree. Through a run-and-pass game they would attempt to score points by hitting a single large post or passing it through a goal formed by two upright posts. Games were known to last for hours or days depending on their purpose and importance.

Three types of sticks were used, representing three different regional traditions, each with its own rules and techniques. The Ojibwe, the Menominee, and other tribes of the Great Lakes and upper Mississippi played with a three-foot stick that had a small, enclosed wooden pocket. In the southeast, the Cherokee, Choctaw, Creek, and Chickasaw played a variation of the game using a pair of small sticks with enclosed webbed pockets with which they trapped the ball. In the Northeast, the tribes of New England and the Iroquois Confederacy played with a four-foot stick whose crook-shaped head formed a large webbed pocket.

This crook-shaped stick was first encountered in the early 17th century by French Jesuit missionaries living and spreading the Gospel among the Huron Indians, who lived in palisaded villages just 100 miles or so north of where Cody and Sid grew up. The “Black Robes,” as the clerics were known to the Indians, called the stick

la crosse

, using a term that the French of the time seem to have associated with any game played with a curved stick. As early as 1374, in fact, a document refers to a stick-and-ball game played in the French countryside called

shouler à la crosse

. In

The Jesuit Relations

, a series of field reports the priests sent back to their superiors, Father Jean de Brébeuf provides the first written account of the game, describing with obvious displeasure the association of this stickball game with ritual healing: “There is a poor sick man, fevered of body and almost dying, and a miserable Sorcerer will order for him, as a cooling remedy, a game of crosse.”

A more detailed description of early Indian lacrosse comes from Baron de Lahontan, a French explorer who in the 1680s was given command of Fort Joseph, a military outpost on the south shore of Lake Huron. Like many other tennis-crazed European explorers of the time, he couldn't help but compare this very different team racket game with the one he had quite likely played back in Paris:

They have a third play with a ball not unlike our tennis, but the balls are very large, and the rackets resemble ours save that the handle is at least 3 feet long. The savages, who commonly play it in large companies of three or four hundred at a time, fix two sticks at 500 or 600 paces distant from each other. They divide into two equal parties, and toss up the ball about halfway between the two sticks. Each party endeavors to toss the ball to their side; some run to the ball, and the rest keep at a little distance on both sides to assist on all quarters. In fine, this game is so violent that they tear their skins and break their legs very often in striving to raise the ball.

Brébeuf and his fellow clerics sought to understand the Indian culture, games included, so they could spread a native form of Catholicism. Although they shared with their earlier Spanish counterparts in Mexico an unwavering mission to convert the “heathen” Indians, the French had a kinder, gentler, and more laissez-faire approach to colonization. As the 19th-century historian Francis Parkman characterized the difference, “Spanish civilization crushed the Indian; English civilization scorned and neglected him; French civilization embraced and cherished him.” The French, whose interests in the New World were largely commercial and centered on the lucrative fur trade, were more likely than the English or Spanish to establish cooperative trade relations and military alliances with the Indians and to recognize tribal rights.

For the Iroquois, Creek, Cherokee, and other tribes, lacrosse was a surrogate for warâ“little brother of war” as some Indians called itâand shared much of the same symbolism. Lacrosse sticks and even players' bodies were sometimes painted with red war paint before important games. In a Creek legend uncovered by historian Thomas Vennum, a father hands his son a war club and sends him into battle, saying, “Now you must play a ball game with your two elder brothers.” Ball games not only served as an important proving ground for young warriors training for battle, but, as lacrosse historian Donald Fisher points out, also provided a diplomatic means of building alliances and avoiding war with neighbors. Ceremonial games brought tribes together to mend political bonds and settle disputes, shoring up tribal confederacies that might otherwise have fallen apart over time. In this way, the Iroquois Confederacy used lacrosse to help establish itself as a dominant military power in the eastern United States and Canada in the late 17th and early 18th centuries.

Ball play of the ChoctawâBall Up

, 1846â50, George Catlin.

In 1763, a group of Ojibwe and Sauk Indians staged a game for the British troops at Fort Michilimackinac in what is now the state of Michigan and succeeded in merging the sport almost seamlessly with war. With the defeat of the French in 1761, the outpost and trading depot had been handed over to the English, whose poor treatment of the Indians provoked the movement known as Pontiac's Rebellion. In honor of the king's birthday, the Indians offered to entertain the English with a game just outside the walls of the fort. The English were kicking back and enjoying the “savage” game, different as it was from their football or tennis, when one of the players fired the ball through the gates of the fort. The warriors rushed into the fort after the ball, traded their lacrosse sticks for weapons that their women had hidden under blankets, and proceeded to massacre the British troops inside. They seized the fort and held it for a year, using their position to extract demands from their new overseers.

As bad as English occupation was for the Iroquois and other eastern Indians, the American Revolution proved to be even worse. The Americans, intent on controlling and expanding their young republic, drove many Iroquois off their lands and into Canada, dividing the Confederacy and initiating a long period of rapid cultural decline. But lacrosse, stripped of some of its religious meaning and importance, hung on and gathered new fans among Canadians and Americans alike. In the years following the revolution, games of lacrosse were recorded in Ontario, played between relocated Mohawk and Seneca groups in an effort to build new alliances. In the 1830s, George Catlin exhibited his romanticized paintings of the “vanishing” Indian, which included depictions of Choctaw Indians playing lacrosse in Oklahoma. In 1844, the first game recorded between Indians and whites took place in Montreal. And just 25 years later, a mere century after the massacre at Michilimackinac, it had been reinvented as the national game of Canada.

O

nondaga is

the

place, I was told. I'd called tribal representatives and the heads of lacrosse programs at several of the other Iroquois nations. If I wanted to learn about the roots of lacrosse, they all told me, the Onondaga Nation is the place to go. “Lacrosse is practically a religion up there,” according to one Oneida Indian I spoke with.

Located just seven miles south of the Carrier Dome, home to the Syracuse Orange, 10-time NCAA Division One champions, Onondaga is a kind of spiritual center and pilgrimage site for anyone looking to worship at the altar of lacrosse. With a population of just 2,000 or so people, the nation has over the years contributed five players to the Canadian Hall of Fame and one to the U.S. Hall of Fame and has fielded more All-Americans per capita than any other community in North America.

For a month or so I'd traded phone calls and emails with Freeman Bucktooth, coach of the Onondaga Redhawks, the nation's team that competes in the Canadian-American box lacrosse association. Freeman played for Syracuse and was captain and lead scorer for the Redhawks for more than a decade. He's also raised and trained four lacrosse-playing sons, including two-time Syracuse All-American Brett Bucktooth. When we spoke, he was gearing up for a trip to Manchester, England, to assistant coach the Iroquois Nationals at the World Lacrosse Championships. The Nationals, an all-Iroquois field lacrosse team that includes seven Onondaga players, was ranked fourth in the world. This, said Freeman, was their year to challenge the U.S. and Canadian national teams for the world title. I wished him luck and told him I'd help him celebrate in a few weeks once they'd returned to Onondaga.

A week later, seated in an airport lounge, I looked up at the TV and there was Freeman being interviewed on CNN. The caption scrolled across the set, “We're lacrosse players, not terrorists.” The team had been prevented from boarding a plane at JFK bound for England because their Iroquois Leagueâissued passports did not meet post-9/11 security and technology requirements. They'd been traveling on these passports without trouble since 1977. Times had changed.

I shot an email to Freeman to show support. The response came back within minutes: “Thanks. It's not looking good.”

In the days that followed, the team made international headlines as they holed up in a Comfort Inn and played scrimmages with local New York City teams. Federation officials met behind closed doors with U.S. immigration officers. Film director James Cameron offered to donate $50,000 to help pay for extra travel expenses. Opposing teams already competing in Manchester expressed disappointment and outrage. “We're playing their game,” commented the American coach of Team Germany in an interview. “And our politics denied them the ability to participate in their game. Just terrible.”