Read The Balanced Scorecard: Translating Strategy Into Action Online

Authors: Robert S. Kaplan,David P. Norton

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Business

The Balanced Scorecard: Translating Strategy Into Action (32 page)

Once targets for financial, customer, internal process, and learning and growth measures have been established, managers can assess whether current initiatives will help achieve these ambitious targets, or whether new initiatives are required. Currently, many organizations have a myriad of initiatives under way—for example, total quality management, time-based competition, employee empowerment, and reengineering.

Unfortunately, these initiatives are frequently not linked to achieving targeted improvement for strategic objectives. Thus, the efforts are managed independently, sponsored by different champions, and compete with each other for scarce resources, including the scarcest resource of all, senior management time and attention. When the Balanced Scorecard is used as the cornerstone of a company’s management system, the various initiatives

can be focused on achieving the organizational objectives, measures, and targets.

While the formulation and mobilization of initiatives to achieve stretch performance targets is largely a creative process, there are three ways in which a planning process, based on the Balanced Scorecard, can improve and channel this creativity:

- The “missing measurement” program

- Continuous improvement programs linked to rate-of-change metrics

- Strategic initiatives, such as reengineering and transformation programs, linked to radical improvement in key performance drivers

The first set of opportunities for performance improvement occurs immediately after the design of a Balanced Scorecard. We invariably discover that data are not available for at least 20% of the measures on the scorecard. Recall the discussion in

Chapter 6

on the paucity of measures for employee development and reskilling. Here too, missing measurements are generally not a data problem. They reveal a management problem: “If you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it.” If data do not exist to support a measure, the management process for a key strategic objective is likely to be inadequate or nonexistent.

As specific examples, the missing measures at National Insurance included such items as regulatory compliance, claims effectiveness, policyholder satisfaction, and competency levels. The missing measures at Metro Bank included deposit service cost, share of target market segment, service error rate, and competency levels. The missing measures at Pioneer Petroleum included customer retention, dealer quality, service quality, and technical competency. For each of these organizations, the missing measures indicated that managers were not currently able to manage several critical processes, now considered essential for strategic success.

For example, Metro’s inability to measure deposit service cost meant that marketing managers could not determine if a customer relationship was profitable. The development of this measure led to extending its activity-based costing model from just measuring only product costs to measuring customer profitability. This initiative ultimately enabled Metro to restructure its prices and service offerings to more targeted market segments. National

Insurance’s inability to measure claims effectiveness meant that it could not tailor its claims management process for the specialist niches in which it intended to operate. The lack of a customized claims management process was a barrier to National’s entire strategy. To correct this gap, the company developed a new claims management approach that could be tailored to individual niches. Pioneer’s inability to measure customer retention meant that its marketing managers could not effectively manage the market segmentation program. In developing the program to obtain this measure, Pioneer’s managers also obtained mechanisms for collecting information about and monitoring targeted consumers’ preferences.

In each of these cases, the missing measure was just the tip of the iceberg. Instituting a process to collect data for the measure led the organization to develop strategic initiatives that would not only gather relevant information but also facilitate better management of a critical internal process. Both factors are essential to superior performance.

Managers must determine whether their stretch targets can be achieved by continuous improvement, such as a total quality management approach to business processes, or whether they require discontinuous improvement, such as a reengineering or transformation program. The TQM approach works within existing processes and applies systematic problem solving to reduce and eventually eliminate defects in the processes (such as late deliveries, non-value-added time within the process cycle, defective products, process errors, and unskilled employees). A discontinuous or reengineering approach develops an entirely new method for accomplishing a process. It assumes that the existing process is flawed in a fundamental way, and requires an entire redesign to fix it.

If a continuous improvement approach is adopted, a rate-of-improvement metric should be used to track whether near-term efforts are on the right trajectory to achieve the ambitious long-term target. One example is the half-life metric developed at Analog Devices (see

Chapter 6

). The half-life measures how many months are required to reduce process defects by 50%. The metric assumes that when TQM teams are successfully applying formal quality improvement processes, they should be able to reduce defects at a constant rate (each 50% reduction in defects takes about the same

number of months). By establishing the rate at which they expect defects to be eliminated from the system, managers can validate whether they are on a continuous improvement trajectory that will yield the desired performance over the specified time period.

One company, a producer of industrial commodities, used the half-life concept to develop an innovative measure. The continuous improvement index was based on eight, strategically important business process measures, including such items as:

- Customer complaint frequency

- Problem resolution period

- Safety incident rate

- Waste levels

- Not right first time percentage

For each factor, the company established a targeted rate-of-improvement, using the half-life philosophy, as well as action initiatives to achieve these improvements. The continuous improvement index measured the percentage of the eight strategic measures that were meeting or exceeding their targets for rates-of-improvement.

Frequently, managers conclude that local problem solving to continuously improve critical processes will not enable the three-to five-year stretch targets to be achieved. This gap signals the need to develop and deploy entirely new ways of accomplishing these processes. Thus, the scorecard approach provides the front-end justification and focus for organizational reengineering and transformation. Rather than just apply fundamental process redesign to any local process, where gains might be easily obtained, managers develop or reengineer processes that will be critical for the organization’s strategic success. And unlike conventional reengineering programs, where the objective is massive cost cutting (the slash and bum rationale), the objective for a reengineering or transformation program need not be measured by dollars saved. The targets for the strategic initiative can be dramatic time reductions in order fulfillment cycles, shorter time-to-market

in product development processes, and enhanced employee capabilities. These nonfinancial targets can be used to justify and monitor strategic initiatives since the Balanced Scorecard has established the linkage of these measures to dramatic improvements in future financial performance.

Most important, when the power of the scorecard is used to drive reengineering and transformation programs, the organization can focus on the issues that create growth, not just those that reduce costs and increase efficiency. Again, the key ingredient for setting priorities for reengineering programs is the cause-and-effect relationships embedded in the Balanced Scorecard. Recall the example of National Insurance (described in

Chapter 7

), which developed a scorecard to clarify its new vision of becoming a specialist insurer. The Balanced Scorecard became the point of departure for reengineering the underwriting, claims management, and agency-management business processes.

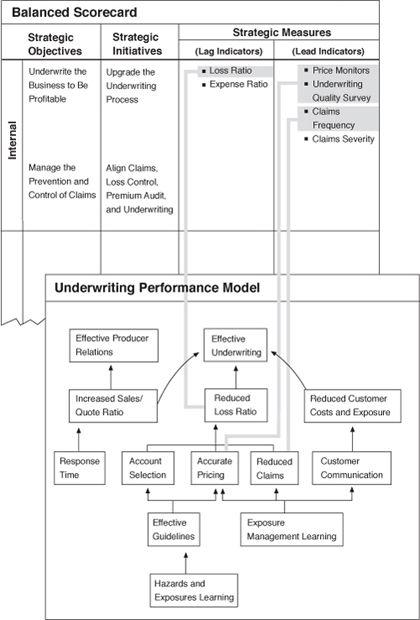

Figure 10-3 illustrates how high-level scorecard measures led to developing a more detailed performance model for the underwriting process. The Underwriting Performance Model identified the factors in the underwriting process that contributed most heavily to the results desired on the Balanced Scorecard. For example, the scorecard outcome measure, loss ratio, was driven by three factors: account selection, accurate pricing, and reduced claims. These factors, in turn, were driven by whether the organization had the capabilities to learn about specific hazards and exposures. As illustrated in Figure 10-4, the Underwriting Performance Model generated the foundation of a Desktop System designed to support the underwriter in the field. Each outcome identified in the performance model generated specifications for the design of an information and work support system. The design specifications identified the more detailed knowledge and experience sharing that was fundamental to the new process design. The performance model, linked to the Balanced Scorecard, allowed the development of an information technology platform that was focused on the strategic objective—improve the underwriting process. The scorecard objective enabled National’s executive team to invest in the long-term drivers, including significant investments in data acquisition and information technology, that would ultimately create financial success for the organization.

Conversely, companies should also review all their current initiatives to determine whether they are contributing to achievement of one or more scorecard objectives. For instance, shortly after the merger that created it, Metro Bank had launched more than 70 different action programs. Each was intended to produce a more competitive and successful institution, but none was integrated into an overall strategy. When building its Balanced Scorecard, Metro executives dropped or consolidated many of these action programs. For example, a marketing effort directed at very high net worth individuals was dropped as was a sales force operational improvement program aimed at enhancing existing low-level selling skills. Managers replaced the latter with a major reskilling program more aligned with the strategic objective to transform salespersons into trusted financial advisers, capable of cross-selling a broad range of newly introduced products.

Figure 10-3

National Insurance’s Performance Measures Reflect Complex Underlying Business Processes

Figure 10-4

National Insurance’s Business Transformation through a Structured Design Process

Obviously, organizations should also link their investment decisions to their strategic plans. While this goal seems obvious and is part of the rhetoric of most strategic planning exercises, many organizations do not, in practice, link their investments to long-term strategic priorities.

2

The justification for most capital investments remains tied to narrow financial measures, such as payback and discounted cash flow and these financial metrics are not necessarily linked to developing strategic capabilities, or even tactical improvements in nonfinancial variables, such as quality, customer satisfaction, and organizational and employee skills.

3

Senior executives deny that they rely exclusively on financial metrics for capital investment decisions. They contend that formal discounted cash flow analysis is only part of a more complex resource-allocation process. They claim to recognize that the impact of an investment on competitors, the organization, and the capital markets may exceed the importance of DCF calculations.

4

Yet most organizations continue to allocate resources using incremental, tactical capital-budgeting mechanisms that stress easily quantified financial measures of near-term cash flows. They do not formally incorporate the development of long-term capabilities into their resource allocation processes and decisions. The Balanced Scorecard overcomes this gap by providing executives with a mechanism to incorporate strategic considerations into the resource allocation process.

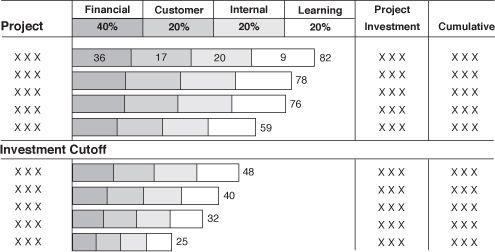

Chem-Pro, a manufacturer of polymer-based industrial products, used a variation of this approach to rationalize its strategic investments. Chem-Pro’s senior executives believed that investment opportunities should not be a series of independent, stand-alone projects that must be evaluated and justified one by one, using traditional financial criteria. Rather, they recognized that to achieve strategic objectives, several linked programs must be initiated, each focused on a different but related factor. Chem-Pro’s Balanced Scorecard identified five strategic initiatives necessary to execute its strategy (see Figure 10-6). For each initiative, the drivers of performance were made explicit. As shown in Figure 10-7, one strategic initiative—increase sales and marketing effectiveness—consisted of nine action programs, each one targeted at a particular driver to increase sales and marketing efficiency. A traditional capital budgeting approach would evaluate each program independently. Many might be considered discretionary expense programs that would require funding from current year operating budgets, not from a budget dedicated to achieving long-term strategic objectives. Managers, operating under a traditional evaluation process, would be unlikely to see the cumulative impact from investing in the entire package of linked initiatives, and, indeed, many of the individual programs would fail in the operating and capital budgeting review process.

Figure 10-5

The Capital Budgeting Process Using Balanced Scorecard Criteria

Figure 10-6

Chem-Pro’s Scorecard and Strategic Initiatives

The Mission

“

We will help our customers be the best by providing world-class services and we will use our expertise to help us win in the marketplace

.”

Figure 10-7

Chem-Pro’s Account Management/Selling Strategic Initiative

Strategic Initiative

:

Dramatically improve the sales and marketing process in order to achieve sales growth that exceeds market growth by 2% and adds 5 points of margin by 1998

The strategic initiative approach used by Chem-Pro ensured that the full complement of programs required to achieve dramatic improvements in future performance would be in place. As the first part of the planning process, all capital budgeting and discretionary expense programs were identified. Only those that supported a strategic initiative were approved. Chem-Pro managers had initially proposed many spending programs that were unrelated to achieving strategic objectives. This first screen eliminated more than 40% of these proposals. A second pass, evaluating the impact of the survivors on the strategic targets, eliminated another 10% of the spending programs. The process also revealed gaps, where no investment programs had been proposed to achieve the ambitious targets for some of

the Balanced Scorecard objectives. Identifying these gaps led to several new initiatives being funded. Chem-Pro used its scorecard as the focal point for all of its discretionary expense and capital investment decisions. After seeing this process function for the first time, one member of the executive committee said: “In the past, we had unfocused activities occurring everywhere. It was like ‘a thousand points of light’ The activities made us a little better off but a lot of effort was counterproductive and much of it was not cumulative. The Balanced Scorecard is like a prism through which all of our investments are focused. Instead of a thousand points of light, we now have a laser. All of our energies are directed at a critical few targets.”

Once the Balanced Scorecard has articulated the strategy and identified the drivers for accomplishing the strategy, companies can:

- identify new strategic initiatives;

- focus a multitude of strategic initiatives—continuous improvement, reengineering, and transformation programs; and

- align investment and discretionary spending programs

to close the gap between ambitious three-to five-year targets for critical scorecard measures and current performance levels. It is this process that most clearly mobilizes the scorecard to translate strategy into action.