The Baking Answer Book (38 page)

Read The Baking Answer Book Online

Authors: Lauren Chattman

Tags: #Cooking, #Methods, #Baking, #Reference

Q

Does mincemeat pie really have meat in it?

A

Mincemeat pie originated in the Middle Ages, as an effort to preserve meat by mixing it with alcohol, fruit, and spices. It is still occasionally made with beef suet and beef in England, Ireland, Brittany, and Canada. Along with plum pudding, mincemeat pie is an essential item on the holiday table in Great Britain.

Most of today’s mincemeat pies, especially in the United States, eschew meat and suet for a mixture of apples, dried fruits, spices, and either butter or vegetable shortening. In spite of their name, they do not have a meaty flavor. The rich filling is more like a spicy and moist fruitcake, and is long-keeping like a fruitcake.

Q

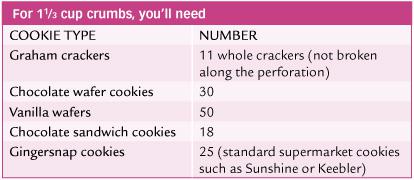

I often see recipes for crumb crusts that give only volume quantities for crumbs. How many graham crackers or wafer cookies make a cup of crumbs?

A

Packaged graham cracker and chocolate cookie crumbs are now sold in the baking aisle of many supermarkets, which is probably why some recipes give quantities in cups rather than in crackers or cookies. But it is always better to take

a few extra minutes to crush cookies into crumbs. Whole cookies stay fresh longer than packaged crumbs, so chances are that a crust made with crumbs from whole cookies will taste fresher than one made with precrushed cookies. Packaged crumbs tend to be crushed almost into a powder or dust. With freshly crushed cookies, your crust will have a chewier, more interesting texture. In my own icebox pie recipes, I generally use about 1 cups of crumbs for a 9-inch crust.

cups of crumbs for a 9-inch crust.

Q

My fruit crisp topping comes out of the oven rather pale, and becomes just plain soggy as it sits on top of the warm fruit. Any suggestions?

A

Recently I’ve seen a few fruit crisp recipes that address this complaint. They call for crisping the topping on a baking sheet in the oven before proceeding. In various versions, the precrisped topping is either sprinkled on the fruit before it is baked, or the fruit is baked separately and the topping is sprinkled on just before serving.

Q

I want to make a cobbler, but it’s the middle of the winter and fresh local fruit is scarce. Is it better to use fresh fruit imported from South America or frozen fruit?

A

In addition to saving money, you will also wind up with a tastier cobbler (or crisp or crumble) by using frozen fruit. Individually quick frozen (IQF) fruit is picked at its peak, when it’s sweetest. Fresh imported fruit, in contrast, is picked early so it can make it to distant supermarkets before spoiling. So, out of season, frozen fruit is preferable to fresh.

Don’t thaw the fruit before you begin making your dessert. Just toss it with sugar, cornstarch, and whatever other filling ingredients are called for in the recipe and proceed, adding 5 to 10 minutes to the baking time.

Q

Is canned fruit any good in cobblers, crisps, etc.?

A

There are a lot of recipes that call for canned fruit, but I much prefer frozen fruit if fresh isn’t available. Canned fruit is already very soft from processing and from sitting in liquid. When baked for a significant amount of time under a heavy layer of biscuit or piecrust, it can get mushy. Frozen fruit, in contrast, maintains its shape during baking.

The exception is canned fruit used on fruit tarts that call for poached fruit. Poaching fresh fruit is time-consuming. In addition, unless your fruit is at a perfect stage of ripeness,

it can start to fall apart when it is cooled and cut, making it impossible to achieve the neat pastry shop look. Canned fruit, in contrast, just needs to be drained, patted dry, and arranged in a pretty pattern before baking. Of course, with any tart that calls for uncooked fruit, only fresh will do.

Q

I’ve made two cherry pies and we’ve eaten only one. Can I freeze it and then thaw it to serve later?

A

It’s possible to freeze a baked and cooled fruit pie, thaw it, and reheat it to crisp the crust, but it will lose a lot of its fresh-baked flavor in the freezer. Next time, if you have any idea that you won’t be needing the second pie, a better option is to assemble the pie and wrap it in a double layer of plastic and then a layer of heavy-duty aluminum foil (to guard against freezer burn) and freeze it unbaked. You can put it in the oven directly from the freezer (make sure your pie plate is safe to go from freezer to oven), adding 10 to 20 minutes of additional baking time.

Pies with baked custard fillings, such as pumpkin or pecan, cannot be frozen this way. If you’d like to do some work ahead of time, make and freeze the pie shells. They will be good for up to two months, tightly wrapped in plastic and foil.

PIE AND TART STORAGE

Most pies and tarts are best eaten soon after they are baked. Ice cream pies and many other icebox pies are exceptions. Here are answers to the questions, “How should I store my pie?” and “How long will it keep?”

Fruit pies.

Cover loosely with plastic wrap and keep at room temperature for up to one day. Some fruit pies, may be edible for another day or two, but the crust will quickly soften and lose its appeal after 24 hours.

Mincemeat pie.

Traditional mincemeat pie, made with beef suet, will keep, covered with plastic wrap and refrigerated, for several weeks. Newer styles of mincemeat pie, made with butter, will last only for several days in the refrigerator.

Nut pies.

These pies, filled with a rich mixture of nuts and eggs, should be stored in the refrigerator, loosely covered in plastic wrap, for up to one day.

Custard pies.

Pies with creamy custard fillings should be loosely covered with plastic wrap and kept in the refrigerator for up to one day.

Cream pies and cakes (including Boston cream and banana cream).

Loosely cover with plastic and refrigerate for up to one day before topping with whipped cream and serving. Once the whipped cream is added, the pies must be eaten.

Meringue pies.

The meringue will quickly begin to break down after the pie cools, so keep this one at room temperature, uncovered, for no more than 3 or 4 hours before serving.

Fruit tarts.

Simple tarts made by topping pastry with fruit and baking can be held at room temperature for up to 6 hours, loosely covered with plastic wrap, before serving.

Icebox pies.

Icebox pies made with crumb crusts generally keep longer than pastry crust pies. If your icebox pie is filled with ice cream, wrap it tightly in a double layer of plastic wrap and freeze it for up to 2 weeks before serving. Cheesecake pies will keep for up to a week, loosely wrapped and refrigerated. Pies filled with mousse or custard will keep for up to 2 days, loosely wrapped in plastic, in the refrigerator. Pudding pies, such as black bottom pie, will keep for up to 2 days. Pies topped with fresh, uncooked fruit should be refrigerated for no longer than a day before serving.

Frangipane tarts.

Frangipane, a kind of cakey nut batter that is spread on top of tart dough before fruit is added, absorbs moisture from the fruit, thus keeping the crust from becoming soggy as quickly as a plain fruit tart. Loosely cover frangipane tarts and keep them at room temperature for up to one day before serving.

Pastry cream tarts.

You can prebake your tart shell several days in advance and keep it wrapped in plastic at room temperature. Similarly, you can make your pastry cream several days in advance and store it, plastic wrap pressed to the surface, until ready to use. But once you assemble the tart, you should serve it within 1 or 2 hours.

Tarte tatin.

This one is best served warm no more than 3 or 4 hours after it comes out of the oven.

Cobblers, crisps, and crumbles.

These desserts lose their charm after several hours out of the oven, so eat them while they’re hot, or at warm room temperature. You can reheat leftovers in a 350°F (180°C) oven for 10 minutes the next day to crisp up the topping.

A BAKED FRUIT DESSERT GLOSSARY

To clear up any confusion about the difference between a brown Betty and a buckle, here is a list of fruit dessert definitions.

Brown Betty.

One of the simplest fruit desserts, a brown Betty is simply a sweet fruit mixture sprinkled with buttered bread crumbs and baked until the topping is crisp.

Buckle.

A buckle is slightly more complicated than some of these other desserts, consisting of a cakelike batter mixed with fruit (most often blueberries), topped with streusel or crumbs.

Clafouti.

A French-style dessert, for which fruit is topped with a custardlike batter and baked.

Cobbler.

Although there are many variations, a basic cobbler is made by topping sweetened fruit with biscuit or cookie dough.

Crisp or Crumble.

Both desserts have a crumb or streusel topping covering the fruit.

Deep-dish pie.

A fruit pie with no bottom crust.

Grunt.

Similar to a cobbler, with fruit on the bottom and biscuit dough on top, a grunt is different in that it is steamed, not baked.

Pandowdy.

A pandowdy is made by covering sweetened fruit with pastry dough. But in contrast to a deep-dish pie, the pastry dough is cut into pieces either before or after baking, and the bubbling juices are allowed to flow over the pastry pieces, which soak them up.

Plate cake.

An upside-down cobbler, in which fruit is topped with rolled biscuit dough and baked; then turned upside down onto a plate (thus the name), so the biscuit becomes a bottom crust.

Slump.

Another word for a grunt.

CHAPTER 9

Layered Pastry Doughs

The pastry doughs discussed in this chapter — puff pastry, croissant, brioche, Danish dough, choux paste, phyllo dough, and strudel — are generally less familiar to American home bakers than the pie and tart doughs from

chapter 8

or the bread doughs in

chapter 10

.

Even people who’ve mastered buttermilk biscuits, layer cakes, and lattice-top pies have likely not attempted from-scratch croissants or brioche. If most of your knowledge comes from sampling napoleons from a French pastry shop, then making anything from puff pastry might seem overly ambitious.

But these items really are no more difficult to produce than American-style baked goods once you understand the techniques. This chapter will answer questions about how these doughs are made and how they are used to create dozens of delicious treats.

Q

Can you describe how to form the butter slab? I’ve never made pastry dough and I’m having trouble picturing it.

A

The tricky and important thing about the butter that you are going to place inside the dough is that it has to be well-chilled but also very soft and malleable so it can be rolled out thin once placed inside the dough, folded, and rolled again without melting or poking holes in the pastry. To get chilled butter to the state where it is both cold and malleable, you must soften it manually by pounding it with a rolling pin. Most recipes will instruct you to sprinkle the counter with flour, place the chilled sticks of butter (usually between two and four depending on how much dough you are making) on the counter, and sprinkle more flour on top of the butter. Then, start to pound the butter, turning it often and sprinkling it with more flour, until it comes together into a smooth mass. What you don’t want is crumbly or crackly butter. It should look like a soft, doughy square when you are through. If at any time while you are pounding the butter gets sticky or begins to melt, wrap it loosely in plastic and refrigerate it until it is cool, and continue until the butter slab is the right consistency — a cool, plastic mass. Then you can roll out your dough and place the butter slab in the center.