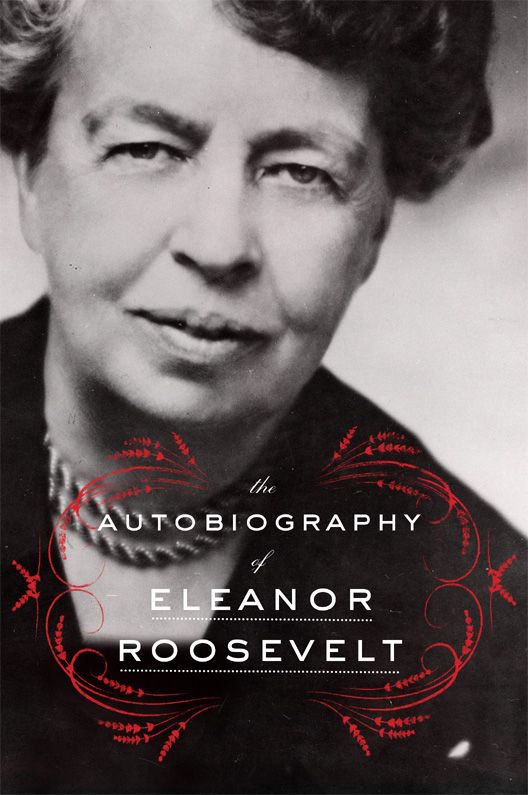

The Autobiography of Eleanor Roosevelt

Read The Autobiography of Eleanor Roosevelt Online

Authors: Eleanor Roosevelt

I

DEDICATE THIS BOOK

to all those who will be spared reading the three volumes of my autobiography and who may find this easier and pleasanter to read.

As I look through it, I think it gives some insight into the life and times in which my husband and I lived, and anything which adds to future understanding I hope will have value.

E.R.

Contents

Four

: Early Days of Our Marriage

Six

: My Introduction to Politics

Eleven

: The 1920 Campaign and Back to New York

Thirteen

: The Private Lives of Public Servants

Fourteen

: Private Interlude: 1921-1927

Fifteen

: The Governorship Years: 1928-1932

Sixteen

: I Learn to Be a President’s Wife

Seventeen

: The First Year: 1933

Eighteen

: The Peaceful Years: 1934-1936

Nineteen

: Second Term: 1936-1937

Twenty-one

: Second Term: 1939-1940

Twenty-two

: The Coming of War: 1941

Twenty-three

: Visit to England

Twenty-four

: Getting on with the War: 1943

Twenty-five

: Visit to the Pacific

Twenty-six

: Teheran and the Caribbean

Twenty-seven

: The Last Term: 1944-1945

Twenty-eight

: An End and a Beginning

Twenty-nine

: Not Many Dull Minutes

Thirty

: Learning the Ropes in the UN

Thirty-one

: I Learn about Soviet Tactics

Thirty-two

: The Human Rights Commission

Thirty-four

: The Long Way Home

Thirty-five

: Campaigning for Stevenson

Thirty-seven

: In the Land of the Soviets

Thirty-eight

: A Challenge for the West

P

ART IV

: The Search for Understanding

Thirty-nine

: Second Visit to Russia

Forty-two

: The Democratic Convention of 1960

Forty-three

: Unfinished Business

AFTERWORD

: Nancy Roosevelt Ireland

I

WANT TO SAY IN THIS BOOK

a special word of thanks to Miss Elinore Denniston. I could not have done, alone, the long and tedious job of cutting that was necessary to abbreviate the three volumes into one nor have added the parts which seemed necessary for a better understanding and for bringing the volume up to date.

Miss Denniston is a most patient, capable, and helpful co-worker. Without her this volume could never have been produced. I thank her warmly and express here my deep appreciation and pleasure in working with her at all times.

E.R.

THIS IS BOTH

an abbreviated and an augmented edition of my autobiography. Abbreviated because, as far as possible, material of only passing interest has been eliminated; augmented by the addition of new material that brings the book up to date. When I first embarked on the story of my life the chief problem I faced was to decide what to put in. Now, in preparing this shorter version, I have had to decide what to leave out. In both cases, the major difficulty lay in trying to see myself and my activities and what happened to me within the framework of a larger picture. It is not easy to attain this kind of perspective because, for me, as for almost everyone, I think, the things that mattered most have not been the big important things but the small personal things.

No one, it seems to me, can really see his own life clearly any more than he can see himself, as his friends or enemies can, from all sides. It is a moral as well as a physical impossibility. The most one can achieve is to try to be as honest as possible.

What my purpose has been I indicated at the end of

This Is My Story.

It occurs to me to wonder why anyone should have the courage or, as so many people probably think, the vanity to write an autobiography.

In analyzing my own reasons I think I had two objectives: One was to give a picture, if possible, of the world in which I grew up and which today is changed in many ways. The other, to give as truthful a picture as possible of a human being. A real picture of any human being is interesting in itself, and it is especially interesting when we can follow the play of other personalities upon that human being and perhaps get a picture of a group of people and of the influence on them of the period in which they lived. The great difference between the world of the 1880’s and today seems to me to be in the extraordinary speeding up of our physical surroundings.

I was for many years a sounding board for the teachings and influence of my immediate surroundings. The ability to think for myself did not develop until I was well on in life and therefore no real personality developed in my early youth. This will not be so of young people of today; they must become individuals responsible for themselves at a much earlier age because of the conditions in which they find themselves in their everyday lives. The world of my grandmother was a world of well-ordered custom and habit, more or less slow to change. The world of today accepts something new overnight and in two years it has become the old and established custom and we have almost forgotten it was ever new.

The reason that fiction is more interesting than any other form of literature to those of us who like to study people is that in fiction the author can really tell the truth without hurting anyone and without humiliating himself too much. He can reveal what he has learned through observation and experience of the inner workings of the souls of men. In an autobiography this is hard to do, try as you will. The more honest you are about yourself and others, however, the more valuable what you have written will be in the future as a picture of the people and their problems during the period covered by the autobiography.

Every individual as he goes through life has different problems and reacts differently to the same circumstances. Different individuals see and feel the same things in different ways, something in them colors the world and their lives. Their experiences and their lessons will be different in each individual case.

To me, who dreamed so much as a child, who made a dreamworld in which I was the heroine of an unending story, the lives of the people around me have continued to have a certain storybook quality. I learned something which has stood me in good stead many times—the most important thing in any relationship is not what you get but what you give.

My Hall family were typical, I think, of the early 1900’s. Somewhere in the background there were people who had worked with their hands and with their heads and worked hard, but the need was no longer there and at that time the material conditions of life seemed stable.

My grandfather Hall typified the group, in his generation, that had reached a goal. He was a gentleman of leisure and enjoyed using his brains. He liked to have the stimulation of intelligent companionship but he did not feel the need to work. In his children many of the qualities of the hardfisted, hardheaded ancestors had faded away, but their world was not so stable as they thought and their money began to slip through their fingers. Today, two generations later, the world has changed so much that many of the younger members of the family have to begin again at scratch and it is interesting to see that, with necessity, many of them develop the same abilities that existed in the working forebears.

This cycle, which I have watched in my family, is one reason why, in our country, it always amuses me when any one group of people take it for granted that, because they have been privileged for a generation or two, they are set apart in any way from the man or woman who is working in order to keep the wolf from the door. It is only luck and a little temporary veneer and before long the wheels may turn and one and all must fall back on whatever basic quality they have.

This idea would never have occurred to my grandmother, for to her the world seemed more or less permanently fixed, but to us today it is a mere platitude and our children and grandchildren accept it without turning a hair.

On the other side of my family, of course, many people whom I have mentioned will be described far better and more fully by other people, except in the case of my father, whose short and happy early life was so tragically ended. With him I have a curious feeling that as long as he remains to me the vivid, living person that he is, he will, after the manner of the people in

The Blue Bird

, be alive and continue to exert his influence, which was always a gentle, kindly one.

The more the world speeds up the more it seems necessary that we should learn to pick out of the past the things that we feel were important and beautiful then. One of these things was a quality of tranquillity in people, which you rarely meet today. Perhaps one must have certain periods of life lived in more or less tranquil surroundings in order to attain that particular quality. I read not long ago in David Grayson’s

The Countryman’s Year

these words: “Back of tranquillity lies always conquered unhappiness.” That may be so, but perhaps these grandparents of ours found it a little easier to conquer unhappiness because their lives were not lived at high tension so constantly. Certainly all of us must conquer some unhappiness in our lives.

Autobiographies are, after all, useful only as the lives you read about and analyze may suggest to you something that you may find useful in your own journey through life. I do not expect, of course, that anyone will find exactly the same experiences or the same mistakes or the same gratifications that I have found, but perhaps my very foolishness may be helpful! The mistakes I made when my children were young may give some help or some consolation to some troubled and groping mother. Because of one’s timidity one sometimes is more severe with the children, or more irritated at trifles, and one feels the necessity to prove one’s power over the only defenseless thing in sight.

We all of us owe, I imagine, far more than we realize to our friends as well as to the members of our family. I know that in my own case my friends are responsible for much that I have become and without them there are many things which would have remained closed books to me.

From the time of my marriage, the life I lived seems more closely allied with the life that all of us know today. It was colorful, active and interesting. The lessons learned were those of adaptability and adjustment and finally of self-reliance and developing into an individual as every human being must.

I have sketched briefly the short trip to Europe after World War I, and yet I think that trip had far-reaching consequences for me. I had known Europe and particularly France, with its neat and patterned countryside, fairly well. The picture of desolation fostered in me an undying hate of war which was not definitely formulated before that time. The conviction of the uselessness of war as a means of finding any final solution to international difficulties grew stronger and stronger as I listened to people talk. I said little about it at the time but the impression was so strong that instead of fading out of my memory it has become more deeply etched upon it year by year.