The Assassins (22 page)

Authors: Bernard Lewis

Tags: #History, #World, #Political Science, #Terrorism, #Religion, #Islam, #Shi'A

Ismaili support could be most effectively mobilized and directed in rural and mountain areas. It was not, however, limited to such areas. Clearly, the Ismailis also had their followers in the towns, where they gave discreet help when needed to the men from the castles proceeding on their missions. Sometimes, as in Isfahan and Damascus, they were strong enough to come out into the open in the struggle for power.

It has usually been assumed that the urban supporters of Ismailism were drawn from the lower orders of society - the artisans, and below them the floating, restless rabble. This assumption is based on the occasional references to Ismaili activists of such social origin, and to the general lack of evidence on Ismaili sympathies among the better-off classes, even those that were at some disadvantage in the Seljuq Sunni order. There are many signs of shi'ite sympathies among the merchants and literati, for example - but they seem to have preferred the passive dissent of the Twelvers to the radical subversion of the Ismailis.

Inevitably, many of the leaders and teachers of the Ismailis were educated townsmen. Hasan-i Sabbah was from Rayy, and received a scribal education; Ibn Attash was a physician, as was the first emissary of Alamut in Syria. Sinan was a schoolmaster, and, according to his own statement, the son of a family of notables in Basra. Yet the New Preaching never seems to have had the seductive intellectual appeal that had tempted poets, philosophers and theologians in earlier times. From the ninth to the eleventh centuries Ismailism, in its various forms, had been a major intellectual force in Islam, a serious contender for the minds as well as the hearts of the believers, and had even gained the sympathy of such a towering intellect as the philosopher and scientist Avicenna (98o-Io37). In the twelfth and thirteenth centuries this is palpably no longer true. After Nasir-i Khusraw, who died some time after Io87, there is no major intellectual figure in Ismaili theology, and even his followers were limited to peasants and mountaineers in remote places. Under Hasan-i Sabbah and his successors, the Ismailis pose terrible political, military and social problems to Sunni Islam, but they no longer offer an intellectual challenge. More and more, their religion acquires the magical and emotional qualities, the redemptionist and millenarian hopes, associated with the cults of the dispossessed, the disprivileged and the unstable. Ismaili theology had ceased to be, and did not again become, a serious alternative to the new orthodoxy that was dominating the intellectual life of the Muslim cities - though Ismaili spiritual concepts and attitudes continued, in a disguised and indirect form, to influence Persian and Turkish mysticism and poetry, and elements of Ismailism may be discerned in such later outbreaks of revolutionary messianism as the dervish revolt in fifteenth-century Turkey and the Babi upheaval in ninteenth-century Persia.

There is one more question that the modern historian is impelled to ask - what does it mean? In religious terms, the New Preaching of the Ismailis can be seen as a resurgence of certain millenarian and antinomian trends, which are recurrent in Islam and which have parallels - and perhaps antecedents - in other religious traditions. But when modern man ceased to accord first place to religion in his own concerns, he also ceased to believe that other men, in other times, could ever truly have done so, and so he began to re-examine the great religious movements of the past in search of interests and motives acceptable to modem minds.

The first great theory on the `real' significance of Muslim heresy was launched by the Count de Gobineau, the father of modern racialism. For him, Shi`ism represented a reaction of the Indo-European Persians against Arab domination - against the constricting Semitism of Arab Islam. To nineteenth-century Europe, obsessed with the problems of national conflict and national freedom, such an explanation seemed reasonable and indeed obvious. The Shia stood for Persia, fighting first against Arab and later against Turkish domination. The Assassins represented a form of militant, nationalist extremism, like the terrorist secret societies of nineteenth-century Italy and Macedonia.

The advance of scholarship on the one hand, and changes in European circumstances on the other, led in the twentieth century to some modifications in this theory of racial or national conflict. Increased knowledge showed that Shi'ism in general, and Ismailism in particular, were by no means exclusively Persian. The sect had begun in Iraq; the Fatimid caliphate had achieved its major successes in Arabia, in North Africa and in Egypt - and even the reformed Ismailism of Hasan-i Sabbah, though launched in Persia and by Persians, had won an extensive following in Arab Syria and had even percolated among the Turcoman tribes that had migrated into the Middle East from Central Asia. And in any case, nationality was no longer regarded as a sufficient base for great historical movements.

In a series of studies the first of which appeared in 1911, a Russian scholar, V. V. Barthold, offered another explanation. In his view, the real meaning of the Assassin movement was a war of the castles against the cities - a last, and ultimately unsuccessful attempt by the rural Iranian aristocracy to resist the new, urban social order of Islam. Pre-Islamic Persia had been a knightly society, to which the city had come as an Islamic innovation. Like the barons - and robber-barons - of mediaeval Europe, the Persian land-owning knights, with the support of the village population, waged war from their castles against this alien and encroaching new order. The Assassins were a weapon in this war.

Later Russian scholars revised and refined Barthold's attempt at an economic explanation of Ismailism. The Ismailis were not against the towns as such, in which they had their own supporters, but against certain dominant elements in the towns - the rulers and the military and civil notables, the new feudal lords and the officially favoured divines. Moreover the Ismailis could not simply be equated with the old nobility. They did not inherit their castles, but seized them, and their support came not so much from those who still owned their estates, as from those who had lost them to new owners - to the tax-farmers, officials and officers who had received grants of land and revenues from the new rulers at the expense of the gentry and peasantry. One view sees Ismailism as a reactionary ideology, devised by the great feudal magnates to defend their privileges against the equalitarianism of Sunni Islam; another as a response, varied according to circumstances, to the needs of the different groups which had suffered from the imposition of the Seljuq new order, and thus embracing both the deposed old ruling class and the discontented populace of the cities; yet another simply as a `popular' movement based on the artisans, the city poor, and the peasantry of mountain regions. According to this view, Hasan's proclamation of the Resurrection was a victory of the `popular' forces; his threats of punishment against those who still observed the Holy Law were directed against feudal elements in the Ismaili possessions, who were secretly faithful to Islamic orthodoxy and hostile to social equality.9

Like the earlier attempts at an ethnic explanation, these theories of economic determination have enriched our knowledge of Ismailism, by directing research into new and profitable directions; like earlier theologies, they have suffered from excessive dogmatism, which has stressed some aspects and neglected others - in particular the sociology of religion, of leadership, and of association. It is obvious that some extension of our knowledge of Islam and its sects, some refinement of our methods of enquiry, are needed before we can decide how significant was the economic element in Ismailism, and what precisely it was. In the meantime both the experience of events and the advance of scholarship in our own time may suggest that it is not so easy to disentangle national from economic factors, or either from psychic and social determinants, and that the distinction, so important to our immediate predecessors, between the radical right and the radical left may sometimes prove illusory.

vNo single, simple explanation can suffice to clarify the complex phenomenon of Ismailism, in the complex society of mediaeval Islam. The Ismaili religion evolved over a long period and a wide area, and meant different things at different times and places; the Ismaili states were territorial principalities, with their own internal differences and conflicts; the social and economic order of the Islamic Empire, as of other mediaeval societies, was an intricate and changing pattern of different elites, estates, and classes, of social, ethnic and religious groups - and neither the religion nor the society in which it appeared has yet been adequately explored.

Like other great historic creeds and movements, Ismailism drew on many sources, and served many needs. For some, it was a means of striking at a hated domination, whether to restore an old order or to create a new one; for others, the only way of achieving God's purpose on earth. For different rulers, it was a device to secure and maintain local independence against alien interference, or a road to the Empire of the world; a passion and a fulfilment, that brought dignity and meaning to drab and bitter lives, or a gospel of release and destruction; a return to ancestral truths - and a promise of future illumination.

Concerning the place of the Assassins in the history of Islam, four things may be said with reasonable assurance. The first is that their movement, whatever its driving force may have been, was regarded as a profound threat to the existing order, political, social and religious; the second is that they are no isolated phenomenon, but one of a long series of messianic movements, at once popular and obscure, impelled by deep-rooted anxieties, and from time to time exploding in outbreaks of revolutionary violence; the third is that Hasan-i Sabbah and his followers succeeded in reshaping and redirecting the vague desires, wild beliefs and aimless rage of the discontented into an ideology and an organization which, in cohesion, discipline and purposive violence, have no parallel in earlier or in later times. The fourth, and perhaps ultimately the most significant point, is their final and total failure. They did not overthrow the existing order; they did not even succeed in holding a single city of any size. Even their castle domains became no more than petty principalities, which in time were overwhelmed by conquest, and their followers have become small and peaceful communities of peasants and merchants - one sectarian minority among many.

Yet the undercurrent of messianic hope and revolutionary violence which had impelled them flowed on, and their ideals and methods found many imitators. For these, the great changes of our time have provided new causes for anger, new dreams of fulfilment, and new tools of attack.

Notes

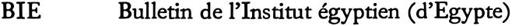

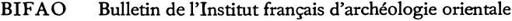

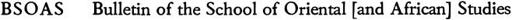

Abbreviations

Other books

My Lady Enslaved by Shirl Anders

Flinx's Folly by Alan Dean Foster

A Murder of Clones: A Retrieval Artist Universe Novel by Rusch, Kristine Kathryn

Robert B. Parker's Wonderland by Ace Atkins

The Lunenburg Werewolf by Steve Vernon

All of Us and Everything by Bridget Asher

Western Widows by Vanessa Vale

Strongest Conjuration by Skyler White

The Seahorse Who Loved the Wrong Lynx by Hyacinth, Scarlet

Strictly Confidential by Roxy Jacenko