The Anthologist (16 page)

Authors: Nicholson Baker

Tags: #Literary, #Poets, #Man-woman relationships, #Humorous, #Modern & contemporary fiction (post c 1945), #General, #Fiction - General, #General & Literary Fiction, #American Contemporary Fiction - Individual Authors +, #Fiction

But Vachel Lindsay, in his day, was big. He went around doing a kind of vaudeville act using poetry. A one-man minstrel show. He was famous for it.

And one day on one of his tours he came to St. Louis, and there he met Sara Teasdale.

Sara Teasdale was a much better poet than Vachel Lindsay was, and he recognized that, and he fell in love with her and chanted his poems to her and beat his drum for her, and later he dedicated a book to her. And eventually he proposed to her.

She didn't marry him, because basically she saw that he was a lunatic. Very unstable and he had seizures from time to time. But they corresponded for years. And as his fame dimmed and people forgot about him, he got crazier, and he began to threaten his wife--he'd married a young teacher-- and he began to have paranoid thoughts that her father was after him. His wife became terrified of him. They had very little money. And when he would go onstage at some provincial women's club, they always wanted him to do his old stuff. "Do the stuff where you bang the drum and sing about Bryant and the Big Black Bucks. Not the new stuff. We don't want the new stuff." And one night back at home he had a fit of rage, and then he calmed down and went down to the basement. His wife called down, "Are you all right, darling?" And he said, "Yes, honey, I'm quite well, thank you--I'll be up shortly."

And then in a little while she heard a sound,

blump.

And she sat up: something is not right. She rushed downstairs and there was Vachel staggering up from the basement, going

erp orp erp.

Obviously in extremis. And she said, "Darling, what's happening?"

And he said, "I drank a bottle of Lysol."

Seriously. He died of it, in agony. And it was good that he died because he could feel that he was getting violent. His time was over. He had contributed what he had to contribute. He could sense that. His kind of poetry, which was so performable and so immediately graspable, had fallen out of favor. People like Ezra Pound--who was even crazier than Vachel Lindsay was, and who also, by the way, beat a drum sometimes when he gave readings--were laughing at him. They thought he was a joke. Modernism was winning its battle with rhyme, and he didn't want to be around when Pound and Williams did their victory dance. So he left the scene.

W

ELL, WHEN

S

ARA

T

EASDALE

found out that Vachel Lindsay had died, she was unhappy, as you can imagine, because in some ways she'd always loved him. She was one of those love-at-a-distance kind of people. She'd loved several men at a distance. And women, too. His death hit her hard, and she was not a healthy woman--she was very very touchy and moody, and sensitive, and hypochondriacal, and a really fine practitioner of the four-beat line.

O shaken flowers, o shimmering trees,

O sunlit white and blue,

Wound me, that I, through endless sleep,

May bear the scar of you.

But she also wrote dirty limericks and then destroyed them. People who read them said they were some of the most incredible dirty limericks they'd ever encountered. Why, why, why did she destroy them? Why? I can hardly bear to think of this loss. Sometimes she suffered from what she called

"imeros"

--a word from Sappho that meant a kind of almost sexual craving for romance. A lust for love.

One day she hit her head on the ceiling of a taxi while it was driving over a pothole in New York, and afterward she said her brain hurt and she dropped into a funk and eventually she took morphine in the bath and died. And not long after that her friend Orrick Johns--who was also from St. Louis and also a poet, who wrote about the whiteness of plum blossoms at night--he killed himself, too. And later Edna St. Vincent Millay fell down the stairs. So the rhymers all began dying out. All except for Robert Frost. Two vast and trunkless legs of Robert Frost stood in the desert.

I'

M NOT A NATURAL RHYMER

. This is the great disappointment of my life. I've got a decent metrical ear--let me just say that right out--and some of my early dirty love poems rhymed because I still believed then that I could force them to, and some of those poems were anthologized in a few places. So I got a reputation as a bad-boy formalist. But these days when I try to write rhyming poetry it's terrible. I mean it's just really embarrassing--it sucks. So I write plums. Chopped garbage. I've gotten away with it for years. And I sometimes feel that maybe if I'd been born in a different time--say, 1883--and hadn't been taught haiku and free verse but real poetry, my own rhyming self would have flowered more fully.

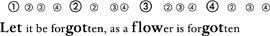

But you know, probably not. Probably my brain just isn't arranged properly. Because think: right now we're in a time in which rhyming is going on constantly. All the rhyming in pop music. There's a lust for it. Kids have hundreds of lines of four-stress verses memorized, they just don't call it four-stress verse. They call it "the words to the songs." They call it Coldplay or Green Day or Rickie Lee Jones or the Red Hot Chili Peppers. "Now in the morning I sleep alone, / Sweep the streets I used to own," says Coldplay. "California rest in peace / Simultaneous release," say the Red Hot Chili Peppers. Four-beat lines. Sometimes the rhymes are trite and sometimes not, and it doesn't matter because the music is the main thing. And I'm sure there will be a geniune adept who strides into our midst in five or ten years. The way Frost did. Sat up in the middle of that spring pool, with the weeds and the bugs all over him. He found the water that nobody knew was there. And that will happen again. All the dry rivulets will flow, and everyone will understand that new things were possible all along. And we'll forget almost all of the unrhymers that have been so big a part of the last fifty years. We'll forget about the wacky Charles Olson, for instance, who was once so big. My poems will definitely be forgotten. They are forgettable. They're simply not memorable. Except maybe for one or two. Maybe people will remember part of "How I Keep from Laughing." People seem to remember that one, sometimes. Garrison Keillor read it on the radio once.

N

EVER MIND THAT

. I soaked my skin graft in saltwater, which wasn't a good idea, but now it's healing nicely. And here's what amazes me. Howard Moss was writing poems at the same time that Allen Ginsberg was. They're so different. Sometimes it's very hard to recapture simultaneity--because even to the people living at the time it didn't feel simultaneous. At the time it felt as if Ginsberg was over here, going "first thought best thought, first thought best thought," and Howard Moss was over here, quietly watching the sun go down through his ice cubes after a day at the office writing a letter accepting a poem sent in by Elizabeth Bishop.

Ginsberg had a poem in

The New Yorker,

too. In the sixties, Moss accepted one of Ginsberg's poems. It's a good one, too. Very long. It spreads out over parts of two pages. It begins ambitiously: "When I Die." Ginsberg's father, Louis Ginsberg, also had poems in

The New Yorker.

His poems rhymed and scanned in the old-fashioned way. But his son Allen was smitten by Walt Whitman's preacherly ampersands and he never recovered.

And one day Ginsberg was giving a talk at the Naropa Institute, where he taught, and somebody asked him what the real rhythm of his poetry was. He was in the middle of saying how bad it was for children to be taught traditional meters--the kind his father used--how the bad iambic rhythm warped their little pure Buddha minds. And somebody at the Naropa Institute said, Well then, tell us, Allen. What is the real rhythm of poetry? And Ginsberg replied that the rhythm of poetry was the rhythm of the body. He said that it was, quote, "jacking off under bridges."

And everyone went, Oh ho, chortle, provocative, ho. Because Ginsberg's referring to jacking off under bridges and that's humorous. And it is, frankly. In fact I really like that Ginsberg would say that. It's the kind of refreshing thing that only he and some of the Beats were able to say.

So yes. Except that it isn't true. Because--try it. Just try to imagine standing under a bridge somewhere, holding a copy of

Howl.

Paperback copy.

You're under a bridge and you're holding your copy of

Howl,

and you read: "I saw the best minds of my generation zonked out on angry Koolaid in the junky slums of West 83rd street, dah dah dah dah dah dah dah dah--" Help! You can't get anywhere with that. Nobody can.

T

HE REAL RHYTHM

of poetry is a strolling rhythm. Or a dancing rhythm. A gavotte, a minuet, a waltz. Remember those inner quadruplets I mentioned? When each beat is divided into four little pulses? Sixteenth notes, they're called, in music. Not duplets, not triplets, but quadruplets. Tetrasyllables. Some meter people call this the paeonic foot, after Aristotle. There's a useless term for you. But listen to the way they can sound:

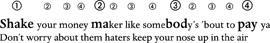

Love has gone and left me and I don't know what to do

That's Edna St. Vincent Millay. Still four beats, but each beat has four inner fuzz-bursts of phonemic energy.

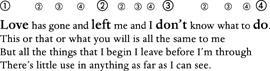

Sara Teasdale did quadruplets, too:

Sara Teasdale did quadruplets, too:

Hear it? People always say that this quadruplet rhythm is for light verse. It doesn't have to be, but it can be. Listen to this four-beater.

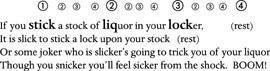

That's light verse by Mr. Newman Levy. One of the lesser Algonquinites. Wrote a number of poems about alcohol, as befits a poet of the Prohibition, using that same quadruplet rhythm. Notice there's no rest on the third line, just as in a traditional ballad. W. S. Gilbert, of Gilbert and Sullivan fame, also uses it--"He's a modern major-general." And A. A. Milne:

When the War is over and the sword at last we sheathe,

I'm going to keep a jelly-fish and listen to it breathe.

And Thomas Bailey Aldrich: "And the heavy-branched banana never yields its creamy fruit." Vachel Lindsay used it: "Where is McKinley, that respectable McKinley"--hear the sixteenth notes in "respectable McKinley"? T. S. Eliot used it, under Vachel Lindsay's influence. "Macavity Macavity there's no one like Macavity." Rappers use it a lot--