The Ancient Alien Question (29 page)

Read The Ancient Alien Question Online

Authors: Philip Coppens

The Goldflyer is one of a series of scale models produced by a team of German enthusiasts who demonstrated that the “bees” found in the gold collections of many museums were actually planes, as von Däniken alleged.

The standoff between archaeologists and Ancient Alien researchers did not break until 1994, when three Germans, Algund Eenboom, Peter Belting, and Conrad Lübbers, decided to create a scale model of the Colombian “airplane.” They wanted to experiment with its flight capabilities. At the same time, they began to draw parallels between the features of this artifact and similar artifacts, which were indeed likely to be bees and insects.

A key point in the debate is that all insects have their wings on the tops of their bodies. However, there were some golden artifacts, like the one from Colombia, that had the wings underneath the body—anatomically incorrect, but valid for an airplane, as we can see on any airport runway, where Boeings and Airbuses all have under-fuselage wings.

The German trio soon realized that the people of South America were able to depict insects and other flying animals anatomically correctly, so if this gold artifact was indeed an insect, then it was an anomaly, and a serious mistake at that. Eenboom, Beltung, and Lübbers therefore concluded that it could not be an insect. Their drawings showed that the design of the artifact corresponded perfectly with the design of a modern jet-engine aircraft—such as the space shuttle and the supersonic Concorde.

In 1996, they were allowed to photograph all of the “golden airplane” specimens on display at the Bremen Overseas Museum in Germany. They were also allowed to measure them and even make impressions of the originals. That same year, Peter Belting created his first scale model—an area he was well-versed in. In fact, it was his interest in the field of scale models that had led to his decision to study the Colombian artifact in the first place. The scale model was baptized “Goldflyer I.” Built at a scale of 16:1, the plane measured 35 inches long, with a wingspan of approximately 3 feet. It weighed 1.5 pounds. A propeller was added to the nose of the plane and the wings were equipped with the necessary flaps and rolls, so that it could take off and land. Early test flights were a success: The plane had a stable flight path and was able to make accurate and comfortable landings. In short, the artifact behaved as a plane was meant to behave, and this was the first demonstrable evidence that the “bee” was a plane.

Next in the development line was the Goldflyer II. This model had the same dimensions as the first, but was equipped with landing gear and a jet engine. The engine itself was a “Fun jet,” able to make 20,000 rotations per minute. The modification from a propeller to a jet engine was made because the original gold artifact did not have a propeller. (If it had, it would have been quite a task for established scientists to have labeled the artifact an insect!)

The problem to overcome was where the jet engine should be placed. On modern airplanes, the jet engines are on the wings (as on modern Boeings and Airbuses) or at the back of the fuselage

(as on the Fokker); the space shuttle has them at the very back of the craft, but its takeoff and flight are vastly different from traditional airplanes, as its flight is aided by booster rockets. In the end, Goldflyer II’s jet engine was positioned at the back of the aircraft, in an unusual position when it comes to what we know from modern aviation, but it was the only position the original gold artifact allowed for such an engine. The insertion of the jet engine in that position was not only a novelty, but also a risk: The air flow into the engine would be different from the accepted standards as used in the airline industry. Subsequent test flights revealed that the plane continued to behave impeccably: Takeoffs and landings were perfect, and its flight path was stable. In short, the insertion of an engine at the back of a plane could be perfectly achieved in modern aviation—the team had just shown modern aviation a novel approach, based on ancient technology!

During the Ancient Astronaut Society World Conference in Orlando, Florida, in August 1997, Belting and Eenboom gave a demonstration of the object in flight. I was a speaker at this conference, which was interrupted at one point so that attendees could go outside and watch the takeoff of the space shuttle from Cape Canaveral, which could be seen on the horizon. But going out to watch the Goldflyer II in action that afternoon was truly one of the most memorable events of my life. I saw how Goldflyer II behaved impeccably during takeoff and flying, and its landing was a thing of beauty.

In 1998, Belting and Eenboom presented at the annual conference of the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Luft and Raumfahrt, where the majority of scientists displayed a positive and open-minded attitude toward their ideas. The notion that the bee was an aircraft was beginning to be accepted, for Belting and Eenboom, along with Lübbers, had already demonstrated that the object could fly. Professor Apel of the Technical University of Bremen, Germany, even concluded, “Anyone who understands

even a little bit about aerodynamics will be able to make one single prognostication: those approximately 1,500-year-old amulets from the pre-Columbian region have such perfect aerodynamic characteristics that they simply have to fly, and very well at that.”

5

It is impressive to see enthusiasts take this approach and demonstrate their case; no one can argue with the flight capabilities of the “insect” as it is. This is what the model looks like, and this is how it flies. In my opinion, Belting, Eenboom, and Lübbers have been able to demonstrate that the artifact is not an insect. At the moment, they have only been able to prove it is an anomaly, an “item” that has all the characteristics of an airplane. But is it an airplane? Or is it something else? Only new evidence, or comparisons with other findings of a similar nature, might give us the final answer.

The Piri Reis Map

Apart from tangible artifacts, knowledge can also be considered best evidence—Robert Temple argued as such in

The Sirius Mystery

, where he tried to demonstrate that the Dogon of Mali possessed knowledge that they simply could not have had. (Alas, in the final analysis, the evidence to support his claim is lacking.)

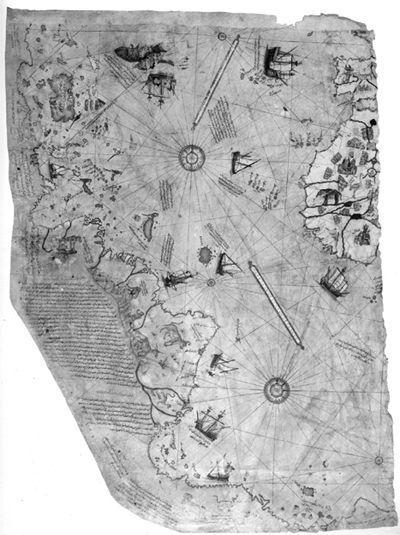

Most people can accept the idea that any advanced civilization would have a detailed understanding of geography and would also have detailed maps of their region. This knowledge leads us to the well-known Piri Reis map, a medieval map designed in 1513 by the Turkish admiral Piri Reis. It was discovered in 1929 in the old imperial Topkapi palace in Istanbul by German theologian Gustav Adolf Deissmann while cataloguing the Topkapi Sarayi library’s non-Islamic items. At the time, it was the only known 16th-century map that showed South America in its proper longitudinal position in relation to Africa. One of

the maps it was based on belonged to Christopher Columbus on his voyage to discover America. From the 1960s onward, largely due to the work of Charles H. Hapgood, who published

Maps of the Ancient Sea Kings

in 1966, the Piri Reis map has been seen as incorporating information that could likely only have been gathered through satellite photography. Thus, as our ancestors clearly are not credited with satellite technology, the map could constitute convincing evidence of an alien presence.

Though dating from 1513, the Piri Reis map is known to have been based on numerous older maps, most now lost. Researchers came to this conclusion because the “center” of the map is the intersection of the Meridian of Alexandria at 30 degrees East and the Tropic of Cancer at 23 degrees North—the old bailiwick of Ancient Egypt. But the part of the map most relevant for Ancient Alien proponents is the manner in which the coastline of Antarctica is depicted: It conforms to pre-glacial conditions of about 12,000 years ago, which suggests that the mapmaker either had a very accurate imagination or had maps at his disposal that dated back thousands of years, allowing him to map a continent that was officially not even known to the Ancient Egyptians—Antarctica was only discovered in 1819 by the American seal hunter Nathaniel Palmer.

There are even more interesting aspects to the Piri Reis map. For example, it shows a large inland lake in Brittany, as well as a large lake present in the Sahara. As mentioned, it is also the first map that showed the correct longitudinal position of Brazil in comparison to Africa—not an easy feat for anyone in 1513! The “other side” of the argument has maintained that more accurate maps of the world

were

created in the 16th century, including the Ribero maps of the 1520s and 1530s, the Ortelius map of 1570, and the Wright-Molyneux map of 1599. However, the idea that there were later, better maps is fine, but the real topic of intrigue with the Piri Reis map is precisely that it was the earliest, and had information on Brazil that was apparently only discovered in 1500.

The Piri Reis map is an early 16th-century map known to have been constructed by synthesizing several other maps. It shows correct longitudes for the Brazilian coastline, and some researchers even suggest that it shows the correct, pre-glacial coastline of Antarctica, a continent that would only be discovered three centuries later.

What about the coastline of Antarctica? Peter Kames and Nick Thorpe in

Ancient Mysteries

write that this mystery was “so shocking that professional archaeologists and historians could not bring themselves to discuss it.” Eventually, historian of cartography Gregory McIntosh did. He feels that the resemblance of the map’s Antarctican coastline to the actual coast of Antarctica is tenuous. He states that cartographers had depicted a massive landmass at the bottom of their maps for centuries before the actual discovery of Antarctica, and that Piri Reis merely followed in this tradition. He also believes that it is possible that the map’s “Antarctic coast” is actually the eastern coastline of South America, skewed to align east-west, for as simple a reason as getting it to fit on the page! There are even more solid concerns, such as the fact that if the landmass pictured is Antarctica, then 2,000 miles of South American coastline are missing from the map. So the map loses all of its accuracy when it comes to the southern half of South America, but picks up its accuracy in its display of Antarctica? Also, Hapgood relied on a seismic survey carried out in 1949 to argue his case for the pre-glacial coastline of Antarctica being depicted, but more recent scientific studies of the continent have revealed that the coastline of Antarctica looks radically different from the results of the 1949 survey.

Either way, it is interesting to note the manner in which science has held the Piri Reis map debate: To explain away the anomalies of the Piri Reis map, traditional scientists have done precisely what the Ancient Alien proponents have done with the Pacal tomb slab, which is to take everything in isolation. When you only look at Antarctica, the similarities could be a coincidence, but if you look at the entire map as a whole, a vastly different picture emerges: It has correct longitude differences, at a time when calculating longitude was practically impossible. It also employed a projection that was more appropriate to ancient Egypt than the Turkish Piri Reis. Hapgood therefore felt confident to conclude that the Piri Reis map was evidence of

one possibility: “It appears that accurate information has been passed down from people to people. It appears that the charts must have originated with a people unknown and they were passed on.”

6

Those people possessed knowledge of our world with which we do not credit our ancient civilizations.

But is it evidence of an alien presence? No. Graham Hancock has argued that the Piri Reis map is evidence of a

lost

civilization, but there is indeed no evidence that this lost civilization had any

alien

influences. So the quest for the best evidence continues.

World Ages

December 21, 2012, is the end date of a Mayan calendar round. For the Mayans, it is the end of the Fourth Age, which began on August 11, 3114

BC

—roughly 5,000 years earlier, when the gods convened in Teotihuacán. This means that the First Age of the Mayan Calendar—the First Creation—was believed to have begun 15,000 or 20,000 years earlier—tens of thousands of years before archaeology accredits humankind’s presence in Middle America, let alone the existence of a Mayan civilization. However inconvenient this Mayan belief is for scientists—who dismiss it as fantasy—this time period does push us back to before the last ice age, and could in theory explain why someone knew the correct coastline of Antarctica in preglacial conditions.

Today, archaeologists are often reported as stating that the Mayans left us very little writings, and how hard it therefore is to draw any definitive conclusions about them. Compare this to what Father Diego de Landa, who accompanied the Conquistadors, boasted about: “We found great number of books...but as they contained nothing but superstitions and falsehoods of the devil we burned them all, which the natives took most grievously, and which gave them great pain.”

7

It is therefore not so much the

Mayans who left us with little, but we who destroyed what we had taken from the Mayans by force, thus creating a blank canvas on which we could rewrite the history of the Mayan world and pretend that they were poor pagan idiots.

Other books

Bearing the Black Ice (Ice Bear Shifters Book 4) by Sloane Meyers

The Billionaire's Heart (The Silver Cross Club Book 4) by Bec Linder

Invitation to Scandal by Bronwen Evans

Dead Man's Time by Peter James

Spy Ski School by Stuart Gibbs

Violet Midnight (Violet Night Trilogy) by Rush, Lynn

2006 - What is the What by Dave Eggers, Prefers to remain anonymous

Hope in Love by J. Hali Steele

A Murderer Among Us by Marilyn Levinson

Some Kind of Normal by Juliana Stone