The Anatomy of Story (67 page)

Read The Anatomy of Story Online

Authors: John Truby

1. Introduce the Godfather, and see what a Godfather does.

2. Start showing how this unique system of the Mafia works, including the hierarchy of characters and the rules by which they are organized and operate.

3. Announce the epic scope of the story so that the audience knows right away one of the main thematic points: the world of this family is not some ghetto they can disdain, but one that stands for the nation.

4. Introduce some of the thematic patterns of identity and opposition that the writers want to weave through the story.

■ Strategy

1. Start with the prototypical Godfather experience, in which the Godfather acts as a judge and exerts power over his unique dominion.

2. Place t

his essential Godfather scene within a larger,

more

complex story world, a wedding, where all the characters who are part of this system are gathered and where the central element of family is emphasized.

■ Desire

Bonasera wants the Don to kill the boys who beat his daughter. Bonasera is a very minor character in this world. But he has no knowledge of the Mafia system. So he is the audience. The writers use him to drive the scene so that the audience can learn the system as he does and can

feel

what it is like to enter and connect with this world. By the way, his full name, Amerigo Bonasera, can be translated as "Good evening, America."

■ Endpoint

Bonasera is trapped by the Don.

■ Opponent

Don Corleone.

■ Plan

Bonasera uses a direct plan, asking the Don to murder the two boys and asking how much he wants to be paid. This direct approach elicits a "no."

In his efforts to reel another person into his web, the Don uses an indirect plan, making Bonasera feel guilty for the way he has treated the Don in the past.

■ Conflict

The Don, angry at the various slights he feels Bonasera has made and continues to make toward him, refuses Bonasera's request. But there is a limit to how much the conflict can build in this scene because the Don is all-powerful and Bonasera is no fool.

■ Twist or Reveal

The Don and Bonasera come to an agreement, but the audience realizes that Bonasera has just made a pact with the devil.

■ Moral Argument and Values

Bonasera asks the Don to kill two boys for beating his daughter. The Don says that is not justice. He then cleverly turns the moral argument back onto Bonasera, arguing that Bonasera has slighted him and treated him with disrespect.

■ KeyWords

Respect, friend, justice, Godfather.

The opening scene of

The Godfather

clearly shows why great dialogue is not just melodic but also symphonic. If this scene were composed only of story dialogue, it would be half the length and one-tenth the quality. Instead, the writers wove the dialogue using three tracks simultaneously, and the scene is a masterpiece.

The endpoint of the scene is Bonasera saying the word "Godfather" at the same moment he is trapped in a Faustian bargain. The beginning of the scene, and the framing line of the entire story, is "I believe in America." This is a value, and it tells the audience two things: they are about to experience an epic, and the story will be about ways of success.

The scene opens with a monologue delivered in a place with almost no detail. Bonasera's monologue doesn't just tell his daughter's sad story; it is filled with values and key words such as "freedom," "honor," and "justice." Don Corleone responds with a slight moral attack, which puts Bonasera on the defensive. And then Don Corleone, acting as the Godfather-judge, gives his ruling.

There's a quick back-and-forth as they disagree over moral argument, in particular about what constitutes justice. And then Bonasera, in the role of the audience, makes a mistake, because he doesn't know the rules of the system. He doesn't know how payment is made here.

At this point, the scene flips, and the Don drives the scene. He makes a moral argument, packed with values like respect, friendship, and loyalty, designed to make Bonasera his slave. Though the Don says he simply wants Bonasera's friendship, Bonasera sees the true goal of the Don's indirect plan. He bows his head and says the key word of the scene, "Godfather." It is followed by the last and most important line of the scene when the Godfather says, "Some day, and that day may never come, I would like to call upon you to do me a service in return."

This line has the same form as the pact the devil makes with Faust. Godfather and devil merge. The "sacred" equals the profane. End of scene. Pow!

Closing Scene

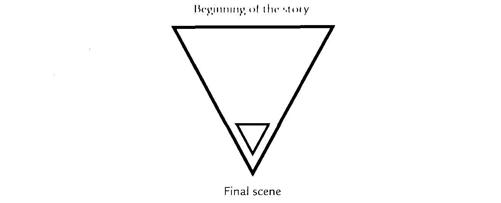

This scene, which is the final point in the upside-down triangle of the full story, is simultaneously a "trial," where Connie accuses Michael of murder, and a coronation. The last scene matches the opening. The prototypical Godfather experience that ended in a pact with the devil is now the new devil crowned king.

■ Position on the Character Arc

Michael is accused of being a

murderer by his sister at the same time he gains his final ascension as the new Godfather. Michael also reaches a kind of endpoint in his marriage to Kay when he poisons it beyond repair.

■ Problems

How to make the moral argument against Michael without having him accept it.

■ Strategy

1. Give Connie the argument, but have her discounted because she's hysterical and a woman.

2.

Deny Michael the self-revelation and give it to Kay instead.

But

make it based not on what Connie says but on what Kay sees in her husband.

■ Desire

Connie wants to accuse Michael of Carlo's murder.

■ Endpoint

The door closes in Kay's face.

■ Opponent

Michael, Kay.

■ Plan

Connie uses a direct plan, accusing Michael of her husband's

murder in front of everyone.

■ Conflict

The conflict starts at an intense level and then dissipates at the end.

■ Twist or Revelation

Michael lies to Kay, but Kay sees what Michael has become.

■ Moral Argument and Values

Connie claims that Michael is a cold-hearted murderer who doesn't care about her. Michael says nothing to Connie and instead refutes her accusations by suggesting she is sick or hysterical and needs a doctor. He then denies Connie's accusations to Kay.

■ Key Words

Godfather, emperor, murderer.

W

riting

S

cenes—

W

riting

E

xercise

9

■ Character Change

Before writing any scene, state your hero's character change in one line.

■ Scene Construction

Construct each scene by asking yourself these questions:

1. Where is the scene positioned on your hero's character arc, and how does the scene take him to the next step on his line of development?

2. What problems must you solve, and what must you accomplish in this scene?

3. What strategy will you use to do so?

4. Whose desire will drive the scene? Remember, this is not necessarily the hero of the story.

5. What is the endpoint of the character's goal in this scene?

6. Who will oppose this character's goal?

7. What plan—direct or indirect—will the character use to accomplish his goal in the scene?

8. Will the scene end at the height of conflict, or will there be some sort of solution?

9. Will there be a twist, surprise, or reveal in the scene?

10. Will one character end the scene by commenting about who another character is, deep down?

■ Scenes Without Dialogue

First, try writing the scenes without dialogue. Let the characters' actions tell the story. This gives you the "clay" you can shape and refine in each successive draft.

■ Writing Dialogue

1. Story Dialogue:

Rewrite each scene using only story dialogue (Track 1). Remember, this is dialogue about what the characters are doing in the plot.

2.

Moral Dialogue:

Rewrite each scene, this time adding moral dialogue (Track 2). This is argument about whether those actions are right or wrong or comments about what the characters believe in (their values).

3.

Key Words:

Rewrite each scene again, highlighting key words, phrases, tagline, and sounds (Track 3). These are objects, images, values, or ideas that are central to the theme of your story.

Think of this process for writing the three tracks of dialogue in the same way that you might draw someone's portrait. First you would sketch the overall shape of the face (story dialogue). Then you would add the major shadings that give depth to the face (moral dialogue). Then you would add the most minute lines and details that make that face a unique individual (key words).

■ Unique Voices

Make sure that each character speaks in a unique way.

A

GREAT STORY lives forever. This is not a platitude or a tautology. A great story keeps on affecting the audience long after the first telling is over. It literally keeps on telling itself. How is it possible for a great story to be a living thing that never dies?

You don't create a never-ending story just by making it so good it's unforgettable. The never-ending story happens only if you use special techniques embedded in the story structure. Before we consider some of those techniques, let's look at the reverse of the never-ending story: a story whose life and power are cut short by a false ending. There are three major kinds of false endings: premature, arbitrary, and closed.

The premature ending can have many causes. One is an early self-revelation. Once your hero has his big insight, his development stops, and everything else is anticlimactic. A second is a desire the hero achieves too quickly. If you then give him a new desire, you have started a new story. A third cause of a premature ending is any action your hero takes that is not believable because it's not organic to that unique person. When you force your characters, especially your hero, to act in an unbelievable way, you immediately kick the audience out of the story because the plot "mechanics" come to the surface. The audience realizes the character is acting a

certain way because

you

need him to act that way (mechanical) and not because

he

needs to (organic).

An arbitrary end is one in which the story just stops. This is almost always the result of an inorganic plot. The plot is not tracking the development of one entity, whether it is a single main character or a unit of society. If nothing is developing, the audience has no sense of something coming to fruition or playing itself out. A classic example of this is the end of

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

Twain tracks Huck's development, but the journey plot he uses literally paints Huck into a corner. He is forced to rely on coincidence and

deus ex machina

to end the story, disappointing those who find the rest of the story so brilliant.