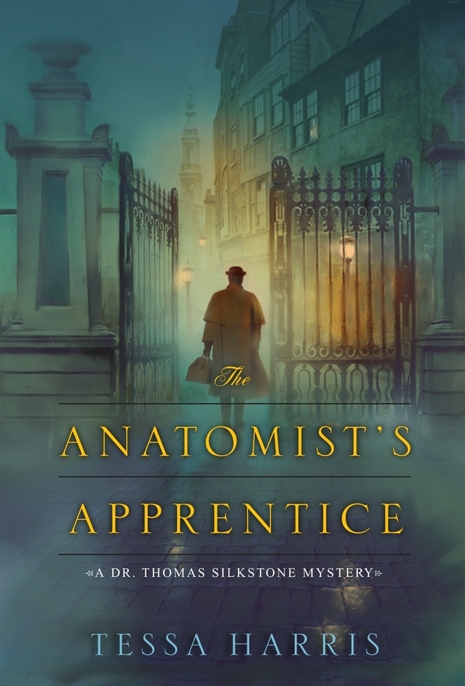

The Anatomist's Apprentice

Read The Anatomist's Apprentice Online

Authors: Tessa Harris

The

ANATOMIST’S APPRENTICE

ANATOMIST’S APPRENTICE

A DR. THOMAS SILKSTONE MYSTERY

TESSA HARRIS

KENSINGTON BOOKS

www.kensingtonbooks.com

www.kensingtonbooks.com

All copyrighted material within is Attributor Protected.

Table of Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Acknowledgments

Epigraph

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Glossary

Copyright Page

Dedication

Acknowledgments

Epigraph

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Chapter 31

Chapter 32

Chapter 33

Chapter 34

Chapter 35

Chapter 36

Chapter 37

Chapter 38

Chapter 39

Chapter 40

Chapter 41

Chapter 42

Chapter 43

Chapter 44

Chapter 45

Chapter 46

Chapter 47

Chapter 48

Chapter 49

Chapter 50

Chapter 51

Chapter 52

Chapter 53

Chapter 54

Chapter 55

Glossary

Copyright Page

To my parents, Patsy and Geoffrey,

my husband, Simon,

and children, Charlie and Sophie—

with love and thanks

my husband, Simon,

and children, Charlie and Sophie—

with love and thanks

Acknowledgments

The character of Dr. Thomas Silkstone was inspired by the many “American” students who came to England and Scotland to study anatomy during the late eighteenth century, several under Dr. John Hunter, a close friend of Benjamin Franklin. These included William Shippen (Junior) and John Morgan, founders of what is now the Medical Faculty of the University of Pennsylvania.

This story was inspired by a murder trial at Warwick Assizes, in England, in 1781. It was the first ever known occasion where an expert witness—in this case, an anatomist—was called.

Although this is a work of fiction and I have taken liberties with many of the facts, changing names, places, etc., I have tried to be as accurate as possible in most historical details.

In my researches I would like to thank Dr. Kate Dyerson for the benefit of her medical knowledge and Katy Eachus and Patsy Pennell for their invaluable opinions.

My thanks must also go to my agent, Melissa Jeglinski, and to my editor, John Scognamiglio, for their belief in me.

—England, 2011

It matters not how a man dies, but how he lives.

The act of dying is not of importance. It takes so short a time.

The act of dying is not of importance. It takes so short a time.

—Dr. Samuel Johnson, 1769

Prologue

T

ime, they say, is a great physician. It is not, however, a good anatomist. Time may help heal the wounds to the soul left by the physical departure of a friend or the death of a loved one, but to an anatomist a corpse, devoid of any signs of life save that of maggots and blowflies, is an altogether different matter. When the very bacteria that once fed on the contents of the intestines begin to digest the intestines themselves then time becomes an enemy.

ime, they say, is a great physician. It is not, however, a good anatomist. Time may help heal the wounds to the soul left by the physical departure of a friend or the death of a loved one, but to an anatomist a corpse, devoid of any signs of life save that of maggots and blowflies, is an altogether different matter. When the very bacteria that once fed on the contents of the intestines begin to digest the intestines themselves then time becomes an enemy.

What you are about to read is the story of a man whose name has been lost in the mists of history, but to whom modern crime fighting owes so much. Just over two hundred years ago anatomists were not afforded the luxury of cold storage to retard the putrefaction process. When a man died, dissection, if it were deemed necessary or desirable, had to be performed quickly before the body attracted flies and the flesh began to rot. The dissecting rooms of Georgian London were no place for those of a delicate constitution at the best of times, let alone in the summer, when the stench of hydrogen sulfide, mingled with methane and ammonia, was enough to make even those with cast-iron stomachs retch.

Dr. Thomas Silkstone did not pretend to be less susceptible to the grotesque characteristics of a rotting corpse than the next man. But he had forced himself, over the last seven years of his practice, since his arrival in London from his native Philadelphia, to overcome the sense of revulsion, the nausea, and the faintness so often suffered by those less experienced. He was still young—at only twenty-five at least twenty years younger than most of his fellow anatomists—yet he had a singularity of purpose and a dedication to his craft that set him apart from the rest of his fraternity. Students would flock to his rooms to watch him work deftly on a corpse, explaining each incision as he did so in a voice whose accent was not quite the King’s English, but a gentleman’s nonetheless.

It is to this young American doctor that today’s pathologists owe their origins. He was the first to record the varying stages of decomposition of the human corpse, the first to study in depth the effects of poisons on the lymphatic system, and the first to be able to gauge the length of time a person had been dead by the entomology on their cadaver. Suddenly he found himself embracing not only anatomy, but the disciplines of chemistry, physics, botany, zoology, and medicine, too. For many, such study and exploration would have been an end in itself and had events not taken the turn they did Dr. Silkstone may well have been satisfied with pursuing pure dissection. Had he chosen to do so, he would undoubtedly have become known as one of the most eminent anatomists of his century. But the events that began to unfurl in the autumn of 1780 turned him from being a straightforward practitioner of dissection, albeit an outstanding one, into something quite new and unheard of among his peers.

On a chilly evening in October that year, in the days when King George III’s government believed it would always rule the world and several independent-minded gentlemen from across the Atlantic were contradicting that notion, Dr. Silkstone received a visit from a young woman that was to change his life and give birth to a new branch of medicine. This lady of good breeding had a sorry story to tell and her circumstances conspired to lure Thomas into a situation that he felt compelled to tackle head-on. A crime may or may not have been committed, but it seemed to Dr. Thomas Silkstone that only science could provide the answers. Using his many and varied scientific skills, he set about endeavoring to solve mysteries using sound logic and pioneering techniques. In short, he became the world’s first forensic scientist and this is the story of his first case.

Chapter 1

The County of Oxfordshire, England,

in the Year of Our Lord, 1780

in the Year of Our Lord, 1780

A

stifled scream came first, shattering the oppressive silence. It was followed by the sound of a heavy footfall. Lady Lydia Farrell rushed out into the corridor. A trail of muddy footprints led to her brother’s bedchamber.

stifled scream came first, shattering the oppressive silence. It was followed by the sound of a heavy footfall. Lady Lydia Farrell rushed out into the corridor. A trail of muddy footprints led to her brother’s bedchamber.

“Edward,” she called.

A heartbeat later she was knocking at his door, a rising sense of panic taking hold. No reply. Without waiting she rushed in to find Hannah Lovelock, the maidservant, paralyzed by terror.

Over in the corner of the large room, darkened by shadows, the young master was shaking violently, his head tossing from side to side. Moving closer Lydia could see her brother’s hair was disheveled and his shirt half open, but it was the color of his skin as his face turned toward the light from the window that shocked her most. Creamy yellow, like onyx, it was as if he wore a mask. She gasped at the sight.

“What is it, Edward? Are you unwell?” she cried, hurrying toward him. He did not answer but fixed her with a stare, as if she were a stranger; then he began to retch, his shoulders heaving with violent convulsions.

In a panic she ran over to the jug on his table and poured him water, but his hand flew out at her, knocking the glass away and it smashed into pieces on the floor. It was then she noticed his eyes. They were straining from their sockets, bulging wildly as if trying to escape, while the skin around his mouth was turning blue as he clutched his throat and clenched his teeth, like some rabid dog. Suddenly, and most terrifying of all, blood started to spew from his mouth and flecked his lips.

Hannah screamed again, this time almost hysterically, as her master lunged forward, his spindly arms trying to grab the window drapes before he fell to the ground, convulsing as if shaken by the very devil himself.

As he lay writhing on the floor, gurgling through crimson-tinged bile, Lydia ran to him, bending over his scrawny body as it juddered uncontrollably, but his left leg lashed out and kicked her hard. She yelped in pain and steadied herself against the bed, but she knew that she alone could be of no comfort, so she fled from the room, shrieking frantically for the servants.

“Fetch the physician. For God’s sake, call Dr. Fairweather!” she screamed, her voice barely audible over the howls that rose ever louder from the bedchamber.

Downstairs there was pandemonium. The unearthly cries, punctuated by the mistress’s staccato pleas, could now be heard in the hallway of Boughton Hall. The footman and the butler emerged and began to climb the stairs, while Captain Michael Farrell put his head around the doorway of his study to see his wife, ashen-faced, on the half landing.

“What is it, in God’s name?” he cried.

There were screams now from another housemaid as more servants gathered in the hallway, listening with mounting horror to the banshee wails coming from the young master’s bedchamber. The house dogs began to bark, too, and their sounds joined together with Lydia’s cries for help in a cacophony of terror that soon seemed to reach a crescendo. All was chaos and fear for a few seconds more and then, just as suddenly as it had left, silence descended on Boughton Hall once more.

Dr. Fairweather arrived too late. He found the young man lying sprawled across the bed, his clothes stained with slashes of blood. His face was contorted into a grotesque grimace, with eyes wide open, as if witnessing some scene of indescribable torment, and his swollen tongue was half protruding from purple lips.

The next few minutes were spent prodding and probing, but at the end of the examination the physician’s conclusion was decidedly inconclusive.

“He has a yellowish tinge,” he noted.

“But what could have done this?” pleaded Lydia, her face tear-stained and drawn.

Dr. Fairweather shook his head. “Lord Crick suffered many ailments. Any one, or several, could have resulted in his demise,” he volunteered rather unhelpfully.

Mr. Peabody, the apothecary, came next. He swore that he had added no more and no less to his lordship’s purgative than was usual. “His death is as much of a mystery to me as it is to Dr. Fairweather,” he concluded.

News of the untimely demise of the Right Honorable The Earl Crick was quick to seep out from Boughton Hall and spread across to nearby villages and into the Oxfordshire countryside beyond within hours. Without a surgeon to apply a tourniquet to stem the flow, it gushed like blood from a severed artery. And of course the tale became even more shocking in the telling in the inns and alehouses.

“ ’Twas his eyes.”

“I ’eard they turned red.”

“I ’eard his flesh went green.”

“ ’E were shrieking like a thing possessed.”

“Maybe ’e were.”

“Mayhap ’e saw the devil ’imself.”

“Claiming his own, no doubt.”

There was a brief pause as the drinkers pondered the salience of this last remark, until suddenly as one they chorused: “Aye. Aye.”

The six men were huddled around the dying embers of the fire at an inn on the edge of the Chiltern Hills. It was autumn and an early chill was setting in.

“And what of ’er, poor creature?”

“ ’Tis said ’e lashed out at ’er.”

“Tried to kill ’er, ’is own flesh and blood.”

“And she so delicate an’ all, like spun gossamer.”

“ ’E was a bad ’un, all right,” said the miller.

Without exception his five drinking companions nodded as their thoughts turned to the various injustices most of them had suffered at their dead lord’s hands.

“ ’E’ll be burning in hell now,” ventured the blacksmith. Another chorus of approval was rendered.

“Good riddance, that’s what I say,” said the carpenter, and everyone raised their tankards. It seemed to be a sentiment that was shared by all those contemplating the young man’s fate.

For a moment or two all was quiet as they supped their tepid ale. It was the blacksmith who broke the silence. “ ’Course you know who’ll be celebrating the most, don’t ye?” He leaned forward in a conspiratorial gesture.

The men looked at one another, then nodded quickly in unison at the realization of this new supposition that had been tossed, like some bone, into their circle.

“ ’

E’ll

be rubbing his ’ands with glee,” smirked the miller, sucking at his pipe.

E’ll

be rubbing his ’ands with glee,” smirked the miller, sucking at his pipe.

“That ’e will, my friends,” agreed the blacksmith. “That ’e will,” and he emptied his tankard and set it down with a loud thud on the table in front of him, with all the emphatic righteousness of a man who thinks he knows everything, but in reality knows very little at all.

Outside in the fading light of the marketplace, the women were talking, too. “Like some mad dog, he was, tearing at his own clothes,” said the lady’s maid, who heard it from her cousin, who knew the stable lad to the brother of the vicar who had attended at the hall on the night of the death.

She was imparting her blood-curdling tale to anyone who would listen to her as she bought ribbon for her mistress at Brandwick market, and there were plenty who did.

So it was that inside the low-beamed taverns and in bustling market squares, in restrained drawing rooms and raucous gaming halls around the county of Oxfordshire, the death was the talk of milkmaids and merchants and gossips and governesses alike. Some spoke of the young nobleman’s eyes, how they had wept blood, and of his mouth, how it had slavered and foamed and how foul utterances and curses had been spewed forth.

The more circumspect would simply say the young earl had died in extreme agony and their thoughts were with his grieving family. Nevertheless, from the gummy old widow to the sober squire, they all listened intently and passed the story on in shades as varied as the turning leaves on the autumn beeches; on each occasion embellishing it with thin threads of conjecture that were strengthened every time they were entwined.

Boughton Hall was a fine, solid country house that was built in the late 1600s by the Right Honorable The Earl Crick’s great-great-grandfather, the first earl. It nestled in a large hollow in the midst of the Chiltern Hills, surrounded by hundreds of acres of parkland and beech woods. Its imposing chimneystacks and pediments had seen better days and the facade was looking less than pristine, but the neglect that it had endured over the past four years under young Lord Crick’s stewardship could be easily remedied with some cosmetic care.

Lady Lydia Farrell loved her ancestral home, but now it was fast taking on the mantle of a fortress whose walls stood between her and the volleys of lies and insinuation that were being fired at her and her husband since her brother’s death. The vicar, the Reverend Lightfoot, tried to comfort her as they sat in the drawing room one evening three days later. His face was mottled, like some ancient, stained map, and he rolled out well-practiced words of comfort as if they were barrels of sack.

“Time,” he told her, “is the great physician.”

She looked up at him from her chair and smiled weakly. His words, although well meant, did not impress her. She forbore his trite platitudes politely but remained silent, fully aware that while time may have been a great physician, it was not a good anatomist. The longer her brother lay in his shroud that held within it the secrets of his death, the sooner time would turn from a physician into an enemy.

Other books

Blood Memory by Greg Iles

Rock Killer by S. Evan Townsend

The Princess & the Pea by Victoria Alexander

08 - The Highland Fling Murders by Fletcher, Jessica, Bain, Donald

Blood of Dragons by Bonnie Lamer

Intentionality by Rebekah Johnson

The English Boys by Julia Thomas

Possessed - Part Two by Coco Cadence

Let Loose by Rae Davies

Doctor On The Ball by Richard Gordon