The Almond Blossom Appreciation Society (4 page)

Read The Almond Blossom Appreciation Society Online

Authors: Chris Stewart

Next morning Michael seemed, if anything, rejuvenated, and as we arrived at the Bellas Artes museum, slipped back into the persona of art expert. In we trooped, about twenty of us, our rubbery trainers squeaking on the marble floors, as he hurried us at great speed through room after room – ‘You don’t want to b-bother with any of this stuff –

constipated

, sycophantic, depressingly conventional’ – until at last we reached a sculpture or painting he thought worthy of our attention.

It was a figure of a kneeling Saint Jerome, carved by Torrigiani. Michael then launched into a virtuoso display of art lore and gossip (‘…and to think that the man who sculpted these delicate features should have broken the nose of Michelangelo and been hounded from Florence!’) before whisking us upstairs to admire Zurbaran’s panel of Saint Hugo presenting a joint of lamb to Carthusian monks. ‘The world’s first icon of vegetarianism,’ Michael declared, pointing out how the lamb had spontaneously combusted to prevent the monks breaking their vow to eschew the eating of meat.

It was a real tour de force and I felt privileged to be a part of it. But it was the evening’s visit to Seville’s massive cathedral that most strongly encapsulated the trip. The cathedral’s builders boasted that successive generations would regard them as mad, in their ambition of scale. But they could not have imagined the true strangeness of the scene that was to unfold. As we arrived at the northwest

gate, where a stuffed crocodile known as the Apothecary’s Lizard hangs from the rafters, it took a while to grasp that uniformed security guards were actually clearing the public from the building. Shortly, one of the guards came over and addressed us in deferential English: ‘If you’d like to come this way, please…’ The cathedral authorities had emptied the building, the largest church in Europe after St Peter’s in Rome, for less than two dozen visitors. I wondered just what sort of donation Jeremy must have put in the poor-box.

The emptiness was all the more disorientating when we were assembled in the choir stalls, and the cathedral

organist

, dressed impeccably in a grey suit, stepped across the marble tiles to put his instrument through its paces. ‘This is the highest note – that little pipe up there,’ he told us, pointing to a tiny pipe nestling miles above among at least four thousand others. He pressed the key and from the tiny pipe came a peep so high and thin that you’d imagine only the keenest-eared bat could appreciate it. ‘And this is the lowest…’ It seemed that the very chasms of the earth were being sundered open somewhere deep in the crypt.

Then he played a few pieces, doubtless full of nuance and emotion, though I couldn’t really enjoy them. Organ

recitals

remind me inescapably of school: first they depress me a little, then send me into an uneasy doze. The Bostonians, too, began dropping off in ones and twos, and it was a relief to be suddenly jarred awake by the organ’s last shuddering bass notes and to be ushered out again into the fresh air and light, by our secret entrance. Looking back I noticed the congregation reforming to take up their private devotions again, while tourists streamed along the main aisles. It was good to be back amid the bustle of the Sevillian throng ourselves, off in search of an evening’s pleasure.

Against my fears and expectations, my role as tour guide had been an easy one – Michael had miraculously appeared for all the big numbers and had managed to appear at all the dinners. However, the final evening set a challenge even he could not defy. We were to be treated to the best seats in the house for the Seville Opera, to see

La Traviata

. But the musicians had gone on strike. They did so at the last minute, so there we were, the Bostonians in their evening wear, all dressed up, with nowhere to go.

‘W-well, this is an opportunity,’ declared Michael to everyone. ‘We can’t have opera, but we can have

literature

. Chris has most kindly agreed to read to you from his m-marvellous book.’ It was hardly on a par with Verdi, I felt, and nor did it seem right, somehow, to be offering this black-leg labour. But we headed to a bar in the Barrio Santa Cruz, ordered a dozen bottles of house wine, and had a genuinely jolly evening of it.

We read the next morning, however, that the conductor at the Opera, exasperated by the intransigence of the

musicians

, had walked onto the stage, swished his tails over the edge of the piano stool and played the entire work of

La Traviata

as a solo piano recital. The crowd were ecstatic and the press proclaimed it one of the city’s greatest ever cultural events. I don’t think I was the only one who felt a bit short-changed.

N

OT LONG AFTER

I

RETURNED

from Seville, I was standing beside the cooker, gathering the nerve to flip a frying pan full of

tortilla de

patatas

onto a plate, when the phone rang.

âTelephoneâ¦' Chloë called out.

âWell it won't be for me, so I'm not getting it,' said Ana.

âNor am I â I'm busy,' I muttered, pushing some bits of potato back into the amorphous mound.

âWell, it won't be for me, as everyone calls me on my mobile,' Chloë noted smugly.

âWell it'll just have to ring, that's all,' I insisted. And so it did, bleating from its place in the draughty corner by the door.

âLook,' argued Ana, âif it's really important, then whoever it is will ring back, won't they?'

The phone finally stopped ringing, and with a

simultaneous

sigh we turned our attention to the neat round disc of egg and potatoes that I had plonked on the table. Then it rang again. Everybody looked at one another accusingly. At last, Chloë broke the silence: âIt must be important; they've called back.'

âAha, but how can you be sure it's the same person? It might be someone else,' I suggested.

It was Ana who finally snapped. Glaring at us she pushed back her chair and went over to the telephone.

â

Hola, dÃgame

,' she growled in the grumpy tone she uses to intimidate time-wasters. Then, turning towards the phone with a surprised smile, she relaxed and her voice took on a new note of warmth. From this subtle shift in tone, Chloë and I deduced that it was Antonia.

âThat was Antonia,' she announced when she finally rejoined us. âShe was ringing from Holland to say that Yacko has escapedâ¦' Antonia was the Dutch sculptor who had been living for the last six years with our neighbour Domingo, in the farm across the river. Yacko was her parrot.

âHow could he, though?' I asked. âI thought she clipped his feathers.'

âThey grow back. You have to keep doing it regularly. Anyway, she's desperate. Domingo, apparently, has spent all day trying to capture the bird, but whenever he gets close Yacko just flits away to the next tree. It was partly his idea that she phoned. They think I'll be more successful.'

It was hard to imagine Domingo abandoning his flock of sheep for a day to wander about the hillside looking for his girlfriend's parrot; and from what I'd gathered, he had never been very keen on Antonia's parrots in the first place. But it was his fault that Yacko had escaped, and Antonia was

frantic, saying that she would have to fly back early from Holland if the bird wasn't recaptured. Antonia had gone back to visit the foundry she uses, near Utrecht, to have some models cast in bronze â one of them a rather fine centaur that Domingo had posed for (the top half, of course).

âShe must be crazy,' I hazarded. âFor the cost of a plane ticket she could buy herself half a dozen African Greys and much finer specimens than that one.'

âThat's hardly the point, though, Chris,' Ana replied frostily. And, as if to echo her words, Porca, who had been sitting on my shoulder, leaned forward to take a pull from my wineglass. (Those who have read before of my abysmal relationship with Ana's parakeet will note that we have reached an uneasy truce â he is willing to tolerate me in order to enjoy my facilities, such as broader shoulders for a perch and a more readily available glass of wine (I top mine up more frequently than Ana.)

âI promised I'd give it a try,' said Ana, âbut how I'm going to find a grey parrot amongst the olive groves of El Duque, let alone catch it, is anybody's guess.'

She had a point. A grey parrot amongst all those silvery leaves would be pretty well camouflaged.

âOh, well. We'd better turn in early and start at first light before he gets restless,' she concluded, with a note of resignation.

It didn't seem worth commenting on, but I couldn't

actually

recall having volunteered for the expedition.Â

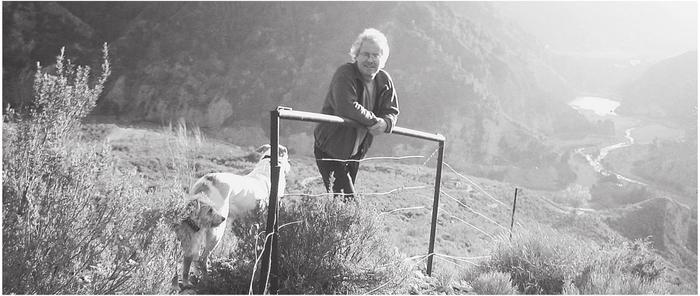

At a quarter past nine, which is as close to first light as Ana gets, we shut the dogs in the house and set off across

the valley. I wasn't quite sure what my role was supposed to be; I'm blind as a plaster cat, as the Spanish would have it, and thus was hardly likely to spot the errant bird. But Ana seemed to think that an extra pair of hands and eyes, however short-sighted, might turn out to be useful.

As we crossed the river I looked up at the great expanse of terraced hillside that rises from El Duque up to Cerro Negro, at what must be a couple of thousand silver-grey olive trees, growing amongst the greyish rock and stone and the dusty grey vegetation. It seemed impossible that we'd find a small grey parrot in all that lot. He could be anywhere by now.

âI can't see how we're going to find Domingo,' I mused as we left the path and struck up the hill. âLet alone the parrot.'

âDon't be so feeble⦠There's Domingo anyway.' And there he was, wandering amongst Bernardo's olive groves, a muscular figure, in old jeans and a threadbare shirt, scanning the horizon with one hand shading his eyes. He saw us and beckoned us over, a brief smile of relief

flitting

across his features.

âHola,

Domingo. How's it going? Any luck?'

â

Nada, nada

⦠Every time I get near him he ups and hops off into the next tree. I was trying to catch him all of

yesterday

, and today I've not caught sight of him. Trouble is, he doesn't like me much â but then, I don't like him so much, either. I tell you, I've had it with parrots. Maybe you'll have more luck, Ana,' he said turning towards her. âYour voice is similar â if you call him, maybe he'll fly to you.'

So we split up and ambled to and fro amongst the olive trees, Domingo and I keeping quiet, and Ana calling every now and then âYacko, Yacko', in imitation of that peculiar

way the Dutch have of speaking with the tongue cloven to the roof of the mouth and the lips not moving. It sounded quite authentic.

After ten minutes or so, we regrouped.

âTell me some words in Dutch, Chris,' Ana demanded.

I'd lived in Amsterdam during a mis-spent period of my youth and could still summon up something of the language. I reeled off obediently one of the few phrases that had somehow stuck in my mind.

âSo what does all that mean?'

âNot too much mayonnaise on the chips, please,' I confessed.

Ana raised an eyebrow. âChris,' she said with an

exasperated

look, âcan you just try and take this seriously?'

The morning drew on with the sun moving high over the hills of the Contraviesa, casting deep shadows among the olive trees and glinting off the Cádiar River as it snaked along the gorge below. I sat in the shade, drowsily following my wife's voice calling in a slightly stagey accent from the terraces below. â

Yacko, Yacko, kom hier, Yacko. Kom hier,

alsjijblieft

' (Yacko, Yacko, come here, if you please), she cried â a dull but courteous admonishment which suited the bird rather well.

Antonia actually has two African Greys. One is an ancient bird who has been in her family for over thirty years, and who can't fly at all as he has lost most of his feathers. He seems content to scuttle about behind the fridge, imitating the radio, which he does uncannily well, and muttering the word âYacko' to himself â Yacko being his name. Then there's the younger one, the escapee we were looking for; his name is Yacko, too.

Yacko

, apparently, means âAfrican Grey' in Dutch. Luckily this was unlikely

to cause any confusion here, as Yacko was probably the only Dutch-speaking African Grey loose in our valley at the time.

It struck me, as I waited for the bird to respond to his lacklustre tag, that the Dutch approach to choosing a name was not so very far removed from that of the rural Spanish. People here take a similarly literal approach: âMulo', for example, is the name of choice for a mule, and âBurro' (meaning âdonkey') for a donkey. And if those names are taken, then there is always the colour of the beast to fall back on: âPardo' (âbrown') or âNegro' (âblack'), for instance.

At least that is how it has been for generations, although changes are creeping in. I know an Irish architect who lives in a village in the high Alpujarras and keeps a mule called âPreciosa'. He told me that his neighbours were so taken with this name for a mule that they'd followed suit and given more imaginative names to their own dogs, mules and even (in one instance) goats. And then there was Manolo, who helps out with the farm work at El Valero. He told me that he was thinking of buying a mule from an English couple in the town: âIt's called Pinfloy,' he confided, looking baffled, wondering if I could shed some light on the matter. I couldn't, though some time later I met the couple, who asked fondly after their mule, âPink Floyd'. Manolo had by then renamed the animal âTordo', which is the

traditional

name for white mules. âIt's a lot easier to shout than “Pinfloy”,' he explained.

My reverie at this point was suddenly interrupted by an urgent call from Ana. She had spotted Yacko. He was sitting contemplating the fruits of freedom from the branch of an olive tree not a stone's throw from where I was sitting.

We all crept silently towards the tree from our respective places. There he was, grey as dust with a flash of bright red tail⦠Now to catch the bugger. I was told to stand stock still, being the likeliest to balls up the operation, while Ana took up position below the tree and began to coax the wretched bird down in her faux-Dutch.

The dim-witted creature seemed to be fooled, and edged closer to Ana to get a better look. Meanwhile Domingo, in accordance with our prearranged plan, crept out along the branch towards the parrot. Beneath his weight the branch lowered towards Ana, who held out the special stick that Antonia uses for training parrots (not to hit them with, but as a portable perch). Yacko stepped meekly onto the stick and thence to Ana's shoulder, where he stared at her fixedly for a bit, wondering if he might not have made a mistake. But, too late â at that instant Domingo leapt and flung his jacket over the foolish bird.

We'd done it. The mission had been a success. With the infuriated creature squawking and screeching from inside the jacket, we walked down towards La Colmena, Domingo's house. We were all feeling rather pleased with ourselves, and the usually phlegmatic Domingo seemed almost light-headed with relief. Suddenly he could look forward with pleasure, rather than dread, to his partner's return. I could sense, too, that Ana, a person of normally modest demeanour, was rather proud of her own part in the adventure.

âWe should celebrate,' I declared, although my own part in the triumph was slightly harder to discern. âA glass of wine is just what we need.'

âI really should be taking the sheep out. I don't like to leave them penned in too long,' Domingo demurred. Then

in an entirely uncharacteristic change of heart: âWell, a glass or two first won't do any harm.'Â