The Air-Raid Warden Was a Spy: And Other Tales From Home-Front America in World War II (28 page)

Read The Air-Raid Warden Was a Spy: And Other Tales From Home-Front America in World War II Online

Authors: William B. Breuer

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #aVe4EvA

A report on the San Francisco kidnapping was given to the FBI, which already had much information on the participants. The victim was Alexander

S. Egorov, a young Russian seaman, who had jumped ship a year earlier and hid out on a chicken farm in Oregon. At that time, the Soviet consulate in San Francisco reported the episode, and the U.S. Immigration Service tracked Egorov down.

The escapee told immigration agents that he had jumped ship because the Soviet police had murdered his father and thrown his mother into a concentration camp. Immigration authorities allowed Egorov to leave San Fran

Spy Nabbed a Second Time

139

cisco aboard a Norwegian ship, but when the vessel docked in Oregon, he fled again.

Soviet secret agents got on Egorov’s trail. For some reason, the fugitive returned to the San Francisco docks, where he was strong-armed onto the Leonid Krasin.

FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover ordered an investigation of the kidnapping, but the State Department, apparently fearful of ruffling Soviet feathers, declared that the FBI did not have jurisdiction in the case. Two days after Egorov was shanghaied in violation of U.S. law, the FBI withdrew and an official of the Immigration Service boarded the freighter in San Francisco. Egorov was brought to a wardroom to be interviewed by the U.S. official. Wearing trousers and an undershirt, the youth’s injuries from the beating were quite visible. He was clearly frightened and in great fear for his life. He said that he did not want to leave the United States, and begged the Immigration official to take him from the ship.

During the tense confrontation, the distraught youth pointed to one of the men who had beaten him severely and dragged him aboard the Leonid Krasin. He was Yakov Lomakin, the consul general at the Soviet consulate in San Francisco.

Lomakin broke into the conversation to claim that he, personally, already had signed the captive aboard as a crew member, and that the U.S. government had no business involving itself with the personnel of Soviet freighters.

When the immigration official departed, Egorov burst out in sobs knowing that he would be sailing to certain death. Early the next day, the Leonid Krasin set a course for the Soviet Union.

26

Spy Nabbed a Second Time

G

UENTHER GUSTAVE MARIA RUMRICH

was only thirty-one years of age in 1943, but he was regarded by the Federal Bureau of Investigation as one of the slickest spies operating in the United States in recent times. A year before Pearl Harbor, Rumrich had been tried on espionage charges after having been captured by the FBI and was given a tap on the wrist—two years in prison.

Rumrich, a slim, soft-spoken man, had been released from prison in 1941 after serving a few months—and he immediately resumed his espionage career, which was paying him handsomely in funds from Adolf Hitler’s Third Reich.

Rumrich was born in Chicago, Illinois, where his father, Alphonse, was secretary of the Austria-Hungarian consulate. When Guenther was two years old his father was transferred to a post in Bremen, Germany, where the boy grew up in war-torn Europe.

At the age of eighteen, Guenther could not find a job. Then he learned that due to his birth in Chicago, he was an American citizen, so he decided to seek his fortune in the United States.

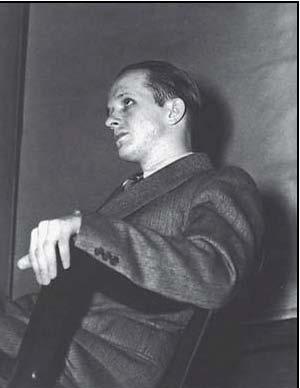

Guenther Rumrich was the slickest and most productive Nazi spy, and the only one convicted twice. (FBI)

Arriving in New York City with a few dollars in his pocket and only several words of English in his vocabulary, he obtained a job as an office boy, but soon proved to be a misfit and was fired. Desperate, he joined the U.S. Army, but in six months he got his fill of military life and deserted.

A curious mixture of shiftlessness, arrogance, and brains, Rumrich was apprehended, court-martialed, and sentenced to six months. In two months he was released and rejoined the Army.

For the next three years he apparently had carried out his duties satisfactorily and was even promoted to sergeant. However, he was detected stealing money from a post hospital, and he deserted again and settled in New York City. There he took a job washing dishes at the Spic and Span restaurant, at 42nd Street and Eighth Avenue, for two dollars per week.

Soon the apparent misfit found his true niche. He wrote a letter to a high-ranking intelligence officer in Germany offering his services as a spy, and months later he was accepted and given the code name Crown.

Rumrich began holding meetings at the Café Hindenburg in the Yorkville section of Manhattan with Nazi agents who crossed the Atlantic masquerading as employees of ocean liners. From these operatives Rumrich received his “shopping lists” from his German controllers in Hamburg.

Rumrich plunged into his job with vigor and ingenuity. Posing as a U.S. Army officer, he telephoned an Army hospital and obtained statistics on the prevalence of venereal disease, which he used as the basis for an accurate estimate on the strength of the military units served by the hospital.

On another occasion Rumrich wrote a letter to a high-ranking Army officer in an effort to get the officer to bring to a New York City hotel complete mobilization and coastal defense plans. Rumrich and an associate plotted to

Scoundrels in the War Effort

141

assault the colonel and take the plans from him, but the scheme fell through when the targeted officer became suspicious.

Rumrich’s downfall came when he attempted to obtain thirty-five blank American passports at the New York City branch of the State Department’s Passport Division, located in the Sub-Treasury Building, at Wall and Pine Streets. In applying for the documents, the spy gave his name as Edwin Weston, and said he was the undersecretary of state. Suspicious, the passport official discovered that there was no one by that name in the State Department. Rumrich was arrested.

Although Rumrich’s innovative espionage plots went awry on occasion, he had succeeded in stealing a large number of U.S. military secrets. His modus operandi was to stroll around army posts and naval bases (America was still at peace) and engage in friendly conversations with officers, during which the Nazi agent was provided much secret information.

Since being freed from prison in 1941, Rumrich resumed his espionage career. He got a job at the Kaiser Shipyards in Richmond, California, where vessels were being built on almost a conveyor-type basis.

Using the alias Joseph De Bors, Rumrich next obtained a job on a ship that made regular runs between San Diego and Alaska, stopping at major ports on the West Coast. Presumably, he had been slipping his observations on these key locales in the war effort to his controllers in Germany. By now, America was fighting Germany.

Rumrich finally tripped himself up when he applied for a Coast Guard pass at Richmond, California, and the FBI was called in. Although he had been conducting widespread espionage for nearly three years after his release from prison, only one government charge could be pinned on him: fraud for using an alias to try to obtain a Coast Guard pass.

After a brief trial in Oakland, California, Rumrich was sentenced to two years in prison.

27

Scoundrels in the War Effort

W

HILE YOUNG AMERICAN MEN

were fighting and dying on far-flung battlefields, in the air, and on the sea, there were weasels entrenched in home-front America. Among those in that category was Amerigo Antonelli and his henchmen, who knowingly manufactured and shipped defective grenades to squeeze out more profit from war contracts. When some GI died in battle because of a faulty grenade, it may well have been one produced by Antonelli.

His firm was called the Antonelli Fireworks Company and was based in Spencerport, New York. For the five years prior to Pearl Harbor, the owner’s reported income was some $2,000 per year. After receiving contracts to build

grenades and incendiary bombs, Antonelli’s salary skyrocketed to $26,000 annually (equivalent to some $300,000 in 2002) plus profits.

Government inspectors had trouble with Antonelli and his foremen from the beginning. When defective grenades were detected by employees, they were supposed to be put into boxes so as not to become mixed with the good ones. But these faulty grenades ended up in the boxes already approved by the inspectors.

Finally, the FBI was brought into the plant. Agents interviewed scores of employees, and many of them swore they had been given orders by Antonelli or his foremen to put only three charges of powder into grenades instead of the necessary four charges.

One young woman told a G-man that she had been instructed: “The hell with what the grenades are like, get out more grenades!” Another employee told of spilled powder being swept up from the floor and then poured into the grenades, dirt and all.

Amerigo Antonelli and several of his foremen were arrested, tried, and convicted of defrauding the government. Although their perfidy had no doubt resulted in the deaths of an unknown number of fighting men, they were let off with taps on the wrist. Antonelli was sentenced to two years in prison and fined $5,000, and the Antonelli Fireworks Company was fined $10,000. Before the war would end, Antonelli would be free to enjoy the remainder of the money his fraud had brought to him.

In the same putrid category as the Antonelli crowd were the officials of the Collyer Insulated Wire Company in Rhode Island. They had cooked up a scheme to foist defective electrical wire on the armed forces, wire that would be used on ships and by the ground forces.

During a routine inspection at the Collyer plant, FBI agents became suspicious when they noticed clues indicating that switches had been removed and the wiring changed on panels on which voltmeters were installed. There also were signs that switches had been removed from an electrical circuit on which galvanometers (instruments used in testing the wire and cable) were operated.

The G-men rapidly found the reason for these unusual changes—a rapid effort to conceal fraud. Some company officials had been using electrical sleight-of-hand to fool the inspectors. By changing the wiring and using an extra switch, the culprits could send 500 volts through a cable and make the voltmeter read 2,000 volts. Therefore, the inspector would approve the cable as being capable of withstanding a 2,000-volt charge. Similar sleight-of-hand techniques were utilized to alter the galvanometer readings.

The FBI agents found that the Collyer representatives were testing the same sample of good wire several times as a method for getting tags of approval for defective reels of wire. The bad reels would be hidden and later the approval tags would be switched to the wire that had been unable to pass examination by inspectors.

“Bomb Japan Out of Existence”

143

In the face of a mountain of evidence collected by the FBI, five officials and employees of Collyer Insulated Wire Company pleaded guilty to charges of fraud against the government. Actually, these miscreants had perpetrated fraud against America’s fighting men. If a battalion commander suddenly lost contact with his units during a crucial fight on the battlefield, thereby putting the entire outfit in jeopardy, it could be that the defective wire came from Collyer Insulated Wire Company.

Amazingly, none of the guilty men was sent to prison. All escaped with fines of only $2,500 to $5,000.

28

“Bomb Japan Out of Existence”

I

N EARLY OCTOBER 1943,

the Washington Times Herald loosed a blockbuster that rocked home-front America. Plastered across its front page was an accurate story of Japanese army atrocities in the Pacific. For various reasons, the government had been keeping a muzzle on this horrible component of the bloody conflict against Japan. But keeping a secret in Washington is akin to trying to hide a rising sun from a rooster.

The Time Herald story was sketchy. Clearly, someone in position to have access to the report, written by Air Corps Lieutenant William “Ed” Dyess, had leaked bits and pieces to a reporter. Dyess had been confined to a Japanese prison camp in the Philippines, escaped to Australia, flew to Washington, and dictated his story of Japanese atrocities perpetrated in what came to be known as the Bataan Death March.