The Adventures of Allegra Fullerton (28 page)

Read The Adventures of Allegra Fullerton Online

Authors: Robert J. Begiebing

We met the sculptor Mr. Powers, finally, calling upon him in his studio. At first I quite liked him for his genial, energetic, far-ranging conversation in a Yankee twang, his face and eyes all alive, but even as he spoke I could not forget my mentor's private reservations about his sculptures: that there was something irrevocably of the Yankee mechanic about them, that he had never cast aside certain restricting elements of the clockmaker, waxworker, and inventor of automata, and that as artist and conversationalist he was so certain of his own answers (as self-educated men often appear to be) that he presumed his own authority over that of Canova, to say nothing of Phidias.

While in Italy with Mr. Spooner, I soon began to understand more about Powers and certain of these American men who hired Italian stone cutters to translate their clay modelings into strange, lifeless precisions of stone. Mr. Spooner suggested that it was as if they strove to follow Thorwaldsen's three-fold, enlivening process (clay model as life, plaster cast as death, sculptured marble as resurrection), but failed to achieve the final phase. I saw for myself, moreover, that despite their protests, the Americans were actually in thrall to the latest school of classicism exemplified by their famous if sometimes unacknowledged mastersâThorwaldsen, Gibson, or whomever. The Americans aspired doggedly to the success of that school, to a certain elegance and finish, to a facile and mannered rhetoric, that it was the great good fortune of us American painters to escape. For there was no remunerative “school” of painting here, no vaunted classic or Italian style. There were before us only the multifarious masterpieces of centuries, from which we might draw inspiration and spirit, solutions to our own technical difficulties, and a rich language of painting spoken by the greatest practitioners of the ageless art.

But at that time, I felt unequipped to judge such matters with self-confidence or certainty. And what did it matter after all if Mr. Powers and other famous Americans were little more than the faithful, ingenious, and uninspired recorders of the most prominent figures of our age?

All during this time, through our first winter and bright amethyst days of spring, Mr. Spooner and I were often thrown together by necessity and common interest. Our viewing of many paintings together seemed to deepen our insight and understandingâthrough a sort of delicious, mutual sympathyâof these Italian masterworks. Our walks together became more frequent as spring approached. On the lofty hills about Florence spring crept in everywhereâin the fecundity of sprouting fig leaves, under the vines in shoots of tender-green grain, and in the sods between furrows with the scarlet flame of wild tulips. And the golden flecks of daffodils, the blues of pimpernels and hyacinths, shimmered beneath the silver olive trees, even as olive and plum flashed forth their snowy blossoms. These early flowers the

contadini

tucked behind their ears and in their waistbands. Everywhere, fragrances intoxicated the traveler, who dreams of Cimabue discovering on high the sketching shepherd boy, Giotto!

These terraced hills we began to climb, winding upward among villas and gardens. Halfway up to Fiesole we passed “Villa Landor,” where the poet lived in privacy amidst the haunts of old poets, philosophers, and Lorenzo il Magnifico. Some have deemed Landor the aloof leader of the “Anglo-Florentine colony,” self-exiled to his high retreat built by Michaelangelo. This became a favored walk: our path would be besieged by wild myrtle and cyclamen in their seasons, and we always passed among pines and mysterious gardens dark with cypress trees. Later, overlooking all Florence after a day of study and work, we watched below us the Duomo and the aerial spires and battlements of Santa Croce swimming in the purples and silvers of evening haze. We seemed to envision the palpable history of triumph and folly, of revenge and ambition, of devotion and tenderness, of every aspiration, every desire and passion bestowed upon the human race and worthy of a poet such as Dante. The midnight assassinations, the tortures and persecutions, the lofty schemes and transcendent works of artâthe good and evil genius of all Europe had been here screwed to a pitch as high as anywhere in the bloody Old World.

Still, in all the early and congenial time between us, I never let on what I had overheard in Paris, but watched Mr. Spooner rather for signs of abatement or increased fervor in his hidden feelings toward me. There were a number of awkward moments for me, knowing privately what I did. And I thought at times, looking back on an event or instance, a word or conversation, that I might have led this wonderful man on more than not. Mrs. Spooner had written several letters during these months to say that she had indeed improved, but that despite Gibbon's growing impatience, she could not say that she was quite restored enough to endure a journey of several thousands of miles by sea. Yet she promised to make every effort before the year was out. None of our own feelings, Mr. Spooner's or mine, came to a crisis until we moved out of the city to avoid the summer heat, the circumstances of which removal are, again, perhaps best, most directly expressed in another of my letters to Mrs. Spooner from those sweet summer days.

Bellosguardo, June 5, 1844

To Mrs. George Spooner

My Dear Mrs. Spooner.

We decided to remove from the city proper and up to Bellosguardoâtaking the second story of a villa among four of us, the better to disperse the expenditure. So we have created our very own school of artists high above the Flower of the Arno!

At one end of the second story, Mr. S. and I share a grand atelier and have a private bedroom each; at the opposite end two English artists, whom we met among the British colony, occupy a similar areaâa gifted young painter named Louise Bellington and her sculptor friend John Goodhue, who once worked in Mr. Powers's studio. We share a common central parlor, not at all large, in this ancient house. I suppose in Boston we should all raise a great scandal, but up here, no one inquires into our private lives, the landlord assuming we are simply enjoying a hillside holiday abroad and painting at our leisureâone couple a father and daughter, the other a man and wife. Goodhue's work causes no difficulty because his workmen and marble dust are all kept below, while he models in clay on his mountain retreat in these long stretches of summer light.

The heat had only begun. But we required more ample space for work, we could save even more on the inexpensive Tuscan rents, and we should remain free of all anxiousness over the choleraâmurmurings of which disease preceded even the full onset of summer. And besides, as you know, everybody leaves in summer anyway; even the barber has his villa. Apartments in the city gape like tombs. In fact, our move was quite sudden; Goodhue had heard of a villa with a floor to let, made inquires, and enthusiastically returned to us with a proposal and a request, should we agree, for an immediate deposit. It sounded like too convenient an arrangement to neglect.

And what a gorgeous prospect! Mr. S. says you must recall the view from the top. Our windows and flying balcony, as it seems, are not too far below the summit. We have many trees and bushes, more than I have seen since arriving in Florence, and a garden and brick terrace.

An English family is in residence for the summer on the floor below, the two daughters (Jenny, age nine, and Mary, age fourteen) taking a large interest in their artist neighbors, but we see little enough of the parents. I believe the father is some sort of wine merchant, on business holiday. The girls' tutor is a dry young stick who eyes us suspiciously and does what she can to discourage the young ladies' playful visits, in the belief, no doubt, that it is her duty to keep her dear charges from corrupting influences. But these, Mrs. Spooner, are spritely little birds who fly out of her hands at every chance.

For a time we tried alternating the chores associated with cooking, but we soon realized it would be easier at little enough expense to hire a woman to cook a meal at the start and end of day. This new arrangement suits us all well, the woman included. As you know, our

contadine

neighbors lead simple lives, living as they do in their ancient little stone dwellingsâpeople in one room, cattle in another. On a beautiful day we walked down to one of those houses with its dark tile roof and long eaves overgrown with yellow moss, its tiny windows in the thick walls, its fanciful chimneyâyou remember the typeâand spoke to an old woman spinning on her rustic, sunny little terrace (two young girls beside her braiding straw) about procuring a cook among the womenfolk. She indicated her daughter within, who appeared to be a woman of about thirty wearing a chemise of coarse, homespun linen with the close-fitting bodice laced behind, and the usual blue, homespun petticoat with an apron over all. She is a very fine worker, and an imaginative cook. She is very neat and rather pretty; we feel fortunate to have found her. Yet I have since seen any number of such graceful women among the handsome

montaine

. When we see them on feast days, I find they dress more like us, but they wear large hats they have braided themselves, instead of bonnets. They also wear two or more necklaces at once, and only later in their lives do these women show bent or injured figures from a life of long and difficult labor, as witness this spinning grandmother in comparison to her still-trim daughter.

I have done studies of these strange, thick little houses in their Arcadian settings, and at times I wish I were more accomplished and knowledgeable musically. Has anyone captured the feeling in music, I wonder, of these peasant songs? I'm sure someoneâprobably of noteâhas. I've heard

contadini

singing in their fields and orchards, as one brother and sister, only last week, who were working in different parts of the same farm. They keep up a most beautiful conversation by each one singing a verse in turn in answer to the other. The dashing Miss Bellington, who has been in Tuscany much longer than I and speaks Italian quite well (and any number of other languages), told me when I mentioned this musical conversation that she has heard lovers on adjoining farms singing alternating verses to one another as well. “It was no doubt shepherds' panpipes in olden times,” she says, “but now the mellifluence of the human voice in the Italian language reigns over Arcadia!” Thus if we have no grand concert hall on our mountainside, we do nonetheless hear a living music among the silver-gray olive trees, dark cypresses, and green footpaths of Tuscan farms.

But I go on too long. Forgive me. May I say, in a phrase, Madame, that we are happyâno one working harder in all Florence than your husbandâand live in a kind of hillside paradise, perhaps the true Arcadia after all. And Mr. S. continues to be honest in praise and blame of my work as I prepare for the great exhibition to be held in the city this September.

Please do come to us as soon as you can, and certainly before this year is out. I see that your poor husband pines for your presence beside him.

Your most affectionate friend,

Allegra Fullerton

TWENTY

Our Pelasgian Arcady

U

ntil our residence at Bellosguardo, neither Mr. Spooner nor I betrayed our complicated and delicate feelings toward one another. We proceeded though our days and nights as master and aspirant, as fellow artists. If anything, I was perhaps more carefully respectful and a little wary of the fragility of feelings on both sides; I certainly had no wish to upset the equilibrium of our relations by confronting him, either subtly or overtly, with what I had overheard in Paris. But it must have been inevitable that in numerous small ways our hearts would grow toward one another, even in our silences, or perhaps in spite of them.

I can not begin to trace out the many influences that released my tender sentiments in such a way as to change my whole relation to this man. Of course our continual companionship contributed to small awakenings within me to a fuller range of his presence. To say nothing of the propinquities of our recent residential arrangements, or of our studies, wanderings, and efforts to do good work in Tuscany. I do recall a particular evening in June. In the afternoon the still air had driven me from my painting room to the shaded terrace. Returning later, I found placed at the foot of my easel, upon which sat a nearly completed oil of our view from Bellosguardo, a glass of water filled with beautiful roses, as if in tribute to what I had accomplished. I had labored long on this atmospheric landscape, and failed severally, and perhaps it was this bright token of Mr. Spooner's sympathy with my trials as much as his tribute to the result, but I began to weepâin happiness rather than sorrowâfor his sweet gesture of understanding and affection.

I had tried to capture on my canvas the steep terraces of olive grove, vineyard, and rooftops below us and the houses and churches sweeping continually from Florence to the mountains in the Arno Valley. Little farms and white villages spread over the plain beset on all sides by mountains. Prato sits way off on another mountainside and Pistoia even at the farthermost edge of the valley, like a thin mirage hovering in the broad sunlight. And the city itself lies between the hills to the right and below, its dome and campanile visible. And high Fiesole, with its gray cathedral tower silhouetted against the gleaming sky, just beyond. (Mr. S. told me that the ancient cathedral dates to the time of Nero and its bishop was a disciple of St. Peter. And Fiesole is far more ancient still). My mountains in the distance rise like waves over the lake-like plain, some hills are bespotted with woods, but most hills I depicted bare-looking because vineyards and orchards can not be seen from our distance. I also tried to suggest the blue shadows that move continually among these mountains and in the plains, alternating with flashes of sunlight that illuminate distant villages and towers. Often we had watched, like gods and goddesses, the genesis of great summer thundershowers sweeping hither and yon.

D

URING THIS TIME

, Mr. Spooner and I also found ourselves together in our rare attendance within that vast social round, which in part Mrs. Greenough orchestrated, of fashionable Florence: the balls at the Pitti, the parties at the Palazzo Ximenes, the Opera (the Greenoughs had a box in the second row at the Pergola), and our single attendance at the British Minister's affairs or “Medici receptions,” as they were sometimes called. This charming Italian society melts all reserve, and once one has been presented, all barriers are removed. And it was through the Greenoughs that we made the acquaintance of a number of the British company of authors, artists, and diplomatic officials who had installed themselves in and about Florence.

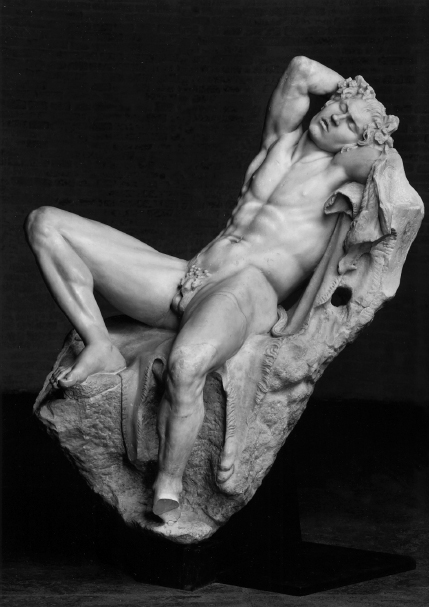

There is in Italy, moreover, a kind of liberality of attitude toward the human body, indeed toward the whole carnal life. Where else is a woman considered virtuous so long as she cleaves to her lover, if not her husband, and observes the conventionalisms of society otherwise? Difference of latitude effects a revolution in morals, even among the Anglo-Saxon ladies here who slip from their lawful lords, often in public view. Where else do our vices become their customs, as in the customary cicisbeism (a “husband within a husband”) which calms the potential disharmonies when marriage-by-estate-and-family has superseded natural inclination? And where else, I wonder, would I have been able to attend lectures on anatomy, even with my letters from Messrs. Powers and Greenough? Where else would men such as these have allowed me to share in their own studies, along with Mr. Spooner, of the human form? On one convivial occasion, after we had been examining Mr. Greenough's studies for Bunker Hill, Achilles and Agamemnon, and other sketches, Mr. Spooner was himself pressed into service for a lark as a model of the male torso. The remaining scales of habit and labor, so to speak, fell from my eyes on the following sultry afternoon when Mr. Greenough had come up to the cooler reaches of Bellosguardo. We were sketching Mr. Spooner (whose manly form looked nothing like his forty-nine years) as he lay half-reclining before us, his arms casually bracing his head, a head apparently engaged in momentary dozing, his loins wrapped by a languid towel. I seemed to see before me an antique, voluptuous figure. Here was no soft cherubic faun of the late sentimental schools, nor even the ancient drunken or resting fauns one sees in casts or in their original state, for all their mild species of sensuality. No, this was the very original of the

Barberini Faun

(if some years advanced beyond the original) luxuriating in the soulless gorgeous sensuality of his muscular, unthinking fleshâyet on the verge of some terrible arousal.

“The Faun of Bellosguardo!” I cried, startling our model to wakefulness. We all laughed. And hereafter Mr. Greenough often addressed him as “My Dear Faunus.”

The Barberini Faun

. With permission from Staatliche Antikesammlugen und Glyptothek, München, Germany. Photo by H. Koppermann.

I began then to reconsider, at varying levels of awareness, my newly vaunted celibacy. And I recalled frequently what Mr. Greenough had once said on the matter, after examining some of these passionate specimens of antique sculpture: “The fire that consumes your house is the same fire that cooks your steak, and though its action as regards yourself is hard, it has under God and Nature only done its duty. If you force a person to celibacy as a means of ensuring chastity, let alone if you build your whole social pile on the like monstrous proposition, you will soon find that nature will do in the moral world what she has always done in the physical. What is denied a natural and easy outlet will make itself an irregular for youâa painful one. The fistula we say is a disease. But no, the fistula replies, âI am a compromise between obstruction and death.'” He paused to look at me, as if to be sure I was not offended.

Mr. Spooner did not hesitate to continue his theme: “Perhaps the day will come when decency will consist in showing a wholesome, clean, and well-developed body instead of hiding a dirty, sick one.” They laughed. “It is possible that then too we shall see that not only the soul but the body also is of God, and that even the brutes whom we despise have learned to make passions harmonize with Providence.”

“Shall we ever see such a time?” Mr. Greenough wondered. “So far, my friends, Christianity is the flower of our strongest yearning after the truth. But is it not also fundamentally imperfectâas long as it remains an intellectual and spiritual aristocracy, dividing our animal from our divine nature, as evil from good?”

To own the truth, it was not long thereafter before Mr. Spooner and I began to live in compatible intimacy, as if in some Pelasgian Eden on our Tuscan mountainside. Never, reader, have I felt happier, never so full of purpose and the excitement of mental discovery with another, never so vital in my life and work, never as the ancient Roman has it, so “inebriated with the warm desire to live and enjoy.” These early halcyon days of immersion in our passion I knew even at the time were not meant to last, not the birthright of poor creatures living beneath the sky, not the legacy passed to a young woman who takes a married manânay, her old friend and master!âfor her lover.

B

Y THAT SUMMER

, as I said, I was working on a painting that I hoped to enter into the annual exhibition of the Academy of Fine Arts, to which Mr. Greenough had been elected as a member of the faculty some years ago. At Mr. Spooner's request, Mr. Greenough had agreed to consider any work I put forward for his recommendation.

I had for some time been examining statues of fauns, satyrs, and Sileni; and I had considered as well their less frequent appearances in paintings. I had examined, also, what I had been able to view of antique representations, whether in cast, copy, or original. Some of these were quite Dionysiacâerotic scenes of great frankness, or ithyphallic figuresâand my idea now was for a muscular faun of quite human character, asleep in some local and actual Tuscan orchard or vineyard, andâif I could achieve itâaltogether most unfamiliar to the modern viewer. That is to say, not idealized; rather, intimating by position, flesh tones, and textures that species of mindless masculine power which had so startled me upon recognizing it in my master, even as he reclined before our busy sketch pads.

At first I had thought to recall Chas Sparhawk as a suitable prototype. But he seemed, finally, cast by nature in proportions too heroic; he might seem on canvas not quite human enough, some figment of the artist's fancy, some mere sensualist's Dream of Arcadia. So I returned to the very object of my revelation and took my studies of Mr. Spooner's torso and attitude as my model form, obscuring only a facial resemblance.

Almost from the beginning, however, questions rose before me like hectoring tribes of Satyrs. Should I place my sensual faun in the context or attitude of one of the numerous Florentine saints I had been studying, and by contrast to my fleshy depiction exaggerate the absence of so completely an otherworldly spirituality? That, I had thought, would force the attention of the viewer upon the ancient attitude toward spirit-and-fleshâa more Panlike figure, translated, Faunuslike, to the hills and rivers of Latium. Or should I forgo the saintly allusions and iconographic tricks and allow my virile figure to speak more directly to my contemporaries?

Beyond that, there was the question of his degree of nakedness.

That question I more easily settled because I soon realized I was determined to make the figure reveal my original idea of him without resorting to the merely scandalous. I allowed the towel to remain as a more appropriate branch of leaves. But this work was, in short, the most difficult thing I had ever attempted: that spirit which impresses upon the viewer an awareness that something more is being expressed than even the artist could have foreseen or calculated, that ever-elusive power I had often felt while attending to a master work executed in the very ebulliency of his genius. Such was my other sweet mania that summer, as if my soul were wandering heedless toward oblivion.

To come to the painful point, however, my muscular faun was ignored by the Academy. Mr. Greenough, who approved of my work, especially understanding something deeper of its provenance, was a wonderful encouragement in my own artistic and financial defeat. For if he had recommended me to the Academy's attention in the first place, he later assured me that now more than ever “false prophets throw their rods on the ground to become serpents,” and (hurt as I might be by the response of the Academy) that the general conditions for artists were still better here than in America, where, to take but one example, Allston's difficult career revealed, as Mr. Greenough said, “the damage an as yet unawakened nation does to her most noble children.”

He looked to see if I believed him, and then went on: “Pay no regard to cavils. Do not fear your own originality or your exile from the crowd of aspirants,” he told me. “For they always seek to reflect the qualities of the favorite of the age, which reflections but show that painting shares the fate of all human pursuits. For is not one picture in thousands worthy of the test of time, the applause of generations, until the very canvas rots, even as the volumes of our tolerable versifiers and romancers are shelved by the thousands when their heady little day is done?”

And as for Academies? Well, he assured me that “they habitually supply their students with a false preference for readiness of hand over power of thought. A system of apprenticeship practiced by the true masters, and not unlike your relation to the elder Spooner, is far preferable because it always has been more favorable to a natural and healthful growth of art than any hotbed culture.” He abjured me to take heart; he offered to help procure commissions, so long as I promised not to hurry back to America in defeat.

Promising to stay in Florence was easy, and I could never have left Mr. Spooner at that time, whatever the turn of events. I was so intoxicated by selfish desire that my only fear, once, was that I was with child. I expressed this concern to Mr. Spooner, who had asked me to explain my sudden aloofness and distraction. We began to worry ourselves sick over it, kept to separate bedchambers once again, and observed every nicety to avoid temptation.