The Adventures of Allegra Fullerton (11 page)

Read The Adventures of Allegra Fullerton Online

Authors: Robert J. Begiebing

Yet, reader, out of such base materials did I finally craft my own liberation and regain my life. After the fifth and final frieze, I noticed that the audience seemed agitated and amused to distraction. Entitled, according to our Harlequin guide, “Cleopatra, Her Three Slave Boys, and Mark Antony,” this tableau featured slave boys painted with burnt cork and the principals, I supposed, with copper watercolors. The suggestiveness, the lewdness, the debasement of this tableau are beyond my audacity to describe.

The audience had gathered heatedly after the performance into a kind of knot by a door which looked to lead directly out onto a street. They were all waiting animatedly for their turn to ascend a stairway which must have led up into the more comfortable regions of the house.

I noticed a man standing against this door, as if to remain out of the press of the crowd. He watched the faces of these passersby, I saw in glimpses, with the brim of his hat pulled low on his forehead, often hiding his eyes. He had remained wrapped in a rough greatcoat (of the sort a seaman might wear) quite buttoned up despite the warmth of the crowded passageways in which we were now moving along so slowly. He caught my eye briefly, and I held his stare.

I cannot now say just what prompted me to expect something from him. I can only say that some desperate instinct, some collection of impressions, led me to believe that this man was different from these others. In spite of his hat and greatcoat, his face, when I could glimpse it, had about it a becoming, poetic gentleness and, perhaps, a worldly wisdom. I can find no other words to quite express my impressions at that moment and among such an ecstatic mob.

Everyone was talking and gesticulating as we moved slowly toward the staircase. Mr. Dudley was conversing with a man who stood next to him. The man was accompanied by a fashionably dressed lady, standing between us now, who nonetheless had the yellow, sodden, dead-alive look of an opium eater. I saw my open moment and took it. I stepped aside just as we passed the stranger who had held my glance.

“Sir,” I said softly, “I feel quite faint. Could you help me, please? Does this door open, I wonder?”

“I'm at your service, Madam,” he said, swung around, glanced back once at Mr. Dudley and his interlocutors, and quietly unlatched and pushed the door open, leaving a narrow exit hardly more than two feet wide. He grabbed my hand and firmly pulled me through the opening and out into a byway of the neighborhood. He quietly pressed the door closed behind us, holding my hand still, and fairly spirited me away and down the chilly night-streets, as if we had been fleeing the flames of Sodom and Gomorrah. In the exhilaration of escape from my long entombment, I asked no questions at first but only made great haste, trying my best to keep up with him.

“Fear not, Dear Woman,” he said. “My design is only to help you. I could see depths of trouble in your face. Just a little farther here and I will explain myself to you, and lead you to proper help and care.”

With that, he continued to lead me down the declivity of streets until we were descending onto the Common, a place familiar enough to me that I felt great comfort and relief, like one who suddenly rushes out of her cell into the full sunshine of midday, even though it was full, moonless night and we traveled briskly under nothing but stars.

Yet I began to fear these new circumstances as my mind came back to me, and I hesitated on the verge of the Common, calling out to my new companion: “Wait! Who are you? And where are you going?”

“Ah,” he said and laughed gently, “those most ancient of questions! Just by this elm here.” He stopped us beside the great trunk. “I am a gentleman, I assure you, who wishes to help you, as it seems you have fallen into some trick or seduction.”

“But who are you?” I persisted, refusing to be drawn any farther into the shadows.

He said nothing immediately, but took off his hat and shook out the long curls about his head.

“It is my habit still as a former seaman,” he said, brushing his hair aside. “I'm not so long returned to Boston that I can crop it yet.” His gentle smile encouraged me.

Then he unbuttoned his long, rough coat and flung it open to expose the elegant dress of a gentleman.

“You see,” he said. “I am a gentleman. Mean you no harm. Only aid and comfort.”

His new demeanor and appearance helped alleviate my apprehensions, but I was still confused.

“My intention is to lead you to a place for women caught in your circumstancesâto the Temporary Home for Fallen Women. I know the matron through other acquaintances. There are those among us in the city, men and women, who have rescued women like yourself.”

“I beg your pardon, sir, but I am not a fallen woman,” I said. “Can you not, rather, take me quickly to Mr. George Spooner's residence? Across the Neck.”

“Spooner the painter?”

“The same. I've worked in his studio and he would provide me adequate protection until I can make other arrangements. I would certainly not want to return to my rooms, from which I was abducted in the first place, nor would I place my brother in any danger in the middle of the night⦠.”

“Word has it that Mr. Spooner has gone to Italy, I'm afraid,” he interrupted me. “But I assure you of the most complete protection in the Home. If you will but allow me, Miss⦠?”

“Mrs. Fullerton. And I repeat, I am no âfallen woman.' I am rather a widow, an artist, who was taken forcibly from her rooms and imprisoned in the very neighborhood where you found me, sir. Despite my being at the bidding of another who schemed to bend me to his will and whim, I have retained, I assure you, every virtue.” I then removed my golden wig and shook in turn my natural hair about my neck and shoulders. I continued speaking as I did so. “I had begun to accompany my tormentor out under the guise of compliance merely to discover an opportunity for escape such as I found by way of your kindness. For which I most heartily thank you, sir.”

“You are very welcome, Mrs. Fullerton. But if I may suggest a means of attaining your security and every simple need at this hour of the night, and with your benefactor Mr. Spooner abroad, I beg you follow me.”

I hesitated, shivering.

“How long were you held against your will?” he asked.

“It is hard to remember precisely. Several months, I should say?”

“Well, then, even the prospect of your rooms remaining untenanted by others is slim indeed. Allow me, as I say, to offer the best temporary resolution to your plight, Mrs. Fullerton.”

I saw little other hope and grew colder every moment, so I allowed him to lead me away quickly through the shadows. I once again asked him who he was. He said that his name was Dana, that he was a recent graduate of Harvard who had for some time read the law and during the past year had served as an instructor in elocution at the college. This appointment he was about to resign in favor of legal practice and the completion of a book recounting his adventures as a common sailor in the California fur trade.

I recognized his name as that of an old, honorable family, and I began to see more fully that I had precious few other possibilities before me that night. I could hardly do worse than he proposed, for a night or two while I thought out my immediate plans and made discreet inquires as to the whereabouts of Tom and Julian.

So we scuttled across the dark Common like thieves avoiding the night watch and rattle. My freedom was to begin among those “fallen sisters” who in some fashion had released themselves from the sale of their own flesh. As we fled under the great elms I began to rejoice in my freedom, feeling suddenly like a child, my life all before me again. I was reminded of the carefree boys I had often seen in their games upon the Common in every season: playing at marbles-in-holes in the malls, or lined up in groups and tending their favorite kites hanging high in the southwest breeze over Park Street, or fishing for pout in the frog pond, or on winter days coasting on Beacon Street, the Park Street mall, and from the foot of Walnut.

As we fled, Mr. Dana intimated that he had the acquaintance of one or two leading members of the New England Female Reform Society, which supported, financially and otherwise, the Temporary Home we now sought for my initial asylum. By the time he left me in the care of Matron, I believed that my falling in with Mr. Dana had been fortuitous indeed. As he and I parted, he promised to make every effort to find Tom and Julian and report back to me.

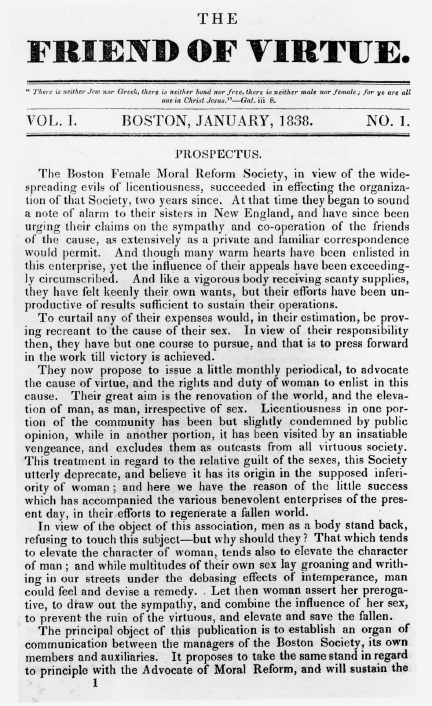

In the meantime, I came under the care of Matron, a woman whose appearanceâher cap and stiff gingham gown rustling like footsteps on autumn leaves, and her thick, creaky shoesâbelied her kindness. She gave me many reassurances as to my safety. And I found myself among other young women who had come here for protection and aid. As she showed me to my bed, Matron handed me an issue of the Society's journal, the

Friend of Virtue

. This one seemed to be the first issue, from 1838, wherein it was explained, when I read it the following morning, that the Society's goals were, first: “to guard our daughters, sisters, and female acquaintances from the delusive arts of corrupt and unprincipled men,” and, second, “to bring back to the paths of virtue those who have been drawn aside through the wiles of the destroyer.” Licentiousness was its chief enemy.

Later issues of the

Friend

came my way during my days at the Home. More and more voices were therein raised for the Rights of Women. But I was more than a little surprised by the many accounts of libertines and profligates, often masked by the firmest respectability, who preyed on their female victims. Most astonishing was the

Friend'

s propensity to name, at times, the prominent patron of an unfortunate, misled womanâwhether he be unmasked in his very pulpit, bench, or legislative hall. And as I read and heard numerous accounts, in their own words, of how this or that woman ended in the brothel, I saw that not so much had changed under the sun since the time of Frances Hill in London. Not only intelligence offices, but stage depots, the new railroad station-houses, and ship ports were all dangerous to a confused or desperate woman, for all those are the haunts of procurers who merely have to lie in wait for their prey to pass before them, whereupon their deceptions begin.

Friend of Virtue.

Courtesy, American Antiquarian Society.

One article, entitled “Slavery in New England,” especially struck home to me. I discovered that my own bondage was not exceptional. Other women too had been locked away in rooms. And many had been far more directly abused, threatened, and forced than I. One woman I met during the week I remained at the Home had been tempted into a brutal trap, as the court revealed, by another woman hired by several brothel keepers to enter the very mills of Lowell in search of likely victims.

Here I found myself among women who were not yet too degraded to spurn offers of refuge. But I knew from even my narrow experience at Mrs. Moore's and with Mr. Dudley that there were many more who would spurn such offers, who had indeed come to view their outlaw lives and labors as preferable to the more respectable forms. And of course there were many still who had discovered all choice in the matter had outrun them, for even appearing once on a court docket would ruin a woman's reputation at any age.

These stories, Matron one day assured me, are all old ones: “If now we hear the West End where you were detained called Satan's Throne and Nigger Hill,” she said, “it was fifty years agoâand even before thatâknown as Mount Whoredom!”

I

NEED NOT EXPAND

upon my days and weeks at the Home: it seems rather more fitting to describe how I came to leave that place of refuge and, eventually, to take up my life once again as a traveling painter.

By week's end, Mr. Dana kept his promise. He returned empty-handed, however. Mr. Spooner, he said, had left with his family for a sojourn in Italy. “And Mr. Julian Forrester,” he gravely announced, “it seems has accompanied the Spoonersâin just what capacity, I know not.”

“And Tom?” I asked, “my brother ⦠Tom?”

“Nothing.” He shook his head and frowned seriously. “He left no word with the landlord either. But as business and my schedule allow, I'll make further inquiries. The important thing now, Mrs. Fullerton, is to find a good place well beyond Boston, beyond the reach of all those who do not have your best interests at heart.”

“By all means, would you please continue every effort you can to find Tom! I would be most grateful.”

He reassured me, explaining that I would soon have a visitor who might be able to suggest a hiding place in “a nascent conclave of visionaries.”

A

ND SO IT HAPPENED

that I met a most astonishing woman. She arrived in a tasteful, full-sleeved, long-waisted gown, lorgnette suspended from her neck, strawberry blond hair center-parted and smoothed, Ã

la Madonna

style, to either side of her fine head. She knew Mr. Dana, and he her, from Cambridgeport school days, from mutual acquaintances, and from her association with Mr. Dana's father. (Indeed, I later discovered that she had once lived for a time in the splendid mansion Judge Danaâthe grandfatherâbuilt in the last century before the Dana family's financial reversals.) She had embarked upon a series of subscription lectures, or “Conversations,” in Boston. But unlike Mr. Dana who, although he had expressed sympathies with the oppressed and seemed to have a nose for cruelty and injustice, apparently viewed the world from a conservative cast of mind, Miss Fuller was reform-minded in nearly every way: anti-slavery, women's rights, religious and communal experimentations.