The Act of Creation (67 page)

Read The Act of Creation Online

Authors: Arthur Koestler

developed' seems to be that it cannot be developed with the existing

theoretical tools without reducing the whole attempt to absurdity. It may

still be possible, and even respectable today for a geneticist to state

that: 'The hoary objection of the improbability of an eye or a hand or a

brain being evolved "by blind chance" has lost its force.' [5] But are

we also to assume that the behaviour-patterns of the digger-wasp, or of

the courtship and fighting rituals of various species have all evolved 'by

pure chance'? This assumption is implied in the doctrine of contemporary

genetics -- though rarely stated in explicit form. Similar assumptions

have been made by extreme behaviourists in the field of learning theory;

there is, in fact, a direct continuity between the doctrine of natural

selection operating on random mutations, and reinforcement operating

on random trials. Both grew out of the same philosophical climate. But

while learning theory is in full retreat from that extreme position,

and has a variety of alternative suggestions to offer, nothing the like

is in sight in the genetics of instinct-behaviour.

it is often difficult, if not impossible, to tell where the 'foundation'

ends and the 'building' starts. But the absence of fool-proof delineations

between 'inheritance', 'maturation', and 'learning' need not prevent us

from recognizing the existence of distinct patterns of animal behaviour

which are (a) stereotyped, (b) species-specific, (c) unlearnt in the

sense that they can be shown to appear, more or less completely, in

animals raised in isolation. It has been objected against this view that

'innate' behaviour, e.g. the pecking of chicks, may partly be due to

prenatal influences, [6] that 'isolation' is never absolute, [7] and

that learning may be practically instantaneous (as in imprinting). Such

arguments are valuable in showing that pure heredity sans environment is

an abstraction; but they do not alter the fact that each animal is born

with a hereditary potential to feed, hoard, court, nest, fight, and care

for its young in certain specific and highly characteristic ways which

are as much part of its native equipment as its morphological features,

and which can be modified by, but are not derived from, imitation and

learning. Only the unbalanced claims of some extreme behaviourists could

temporarily obscure the obvious fact that 'if the physical machinery for

behaviour develops under genetic control, then the behaviour it mediates

can scarcely be regarded as independent of inheritance'. [8]

experience. To quote the convergent definitions of one ethologist and

one psychologist: 'Learning is a central nervous process causing more

or less lasting changes in the innate behavioural mechanisms under

the influence of the outer world. . . .' [9] 'Learning is a process

by which an activity originates or is changed through reacting to

an encountered situation, provided that the characteristics of the

change in activity cannot be explained on the basis of native response

tendencies, maturation, or temporary states of the organism (fatigue,

drugs, etc.).' [10]

it is virtually impossible to draw a precise distinction between the

'innate' and 'acquired' aspects or components in the adult animal's

behaviour. Even the discrimination of biologically relevant sign-Gestalten

in the environment seems to require a minimum of experience; and

one must conclude, with Thorpe, that 'since comparison involves

learning, an element of learning enters into all orientation and all

perception. Accordingly it is suggested that the difference between inborn

and acquired behaviour is of degree rather than kind; it becomes, in fact,

a difference chiefly of degree of rigidity and plasticity.' [11] In

the terms of our schema, what is inherited is the specific and invariant

factor in the native skill -- its code. Its more or less flexible matrix

develops through learning from experience. To quote Thorpe again:

In each example of true instinctive behaviour there is a hard core

of absolutely fixed and relatively complex automatism -- an inborn

movement form. This restricted concept is the essence of the instinct

itself. Lorenz originally called it Erbkoordination or "fixed

action pattern". Such action patterns are items of behaviour in every

way as constant as anatomical structures, and are potentially just

as valuable for systematic, philogenetic studies. Every systematist

working with such groups as birds or higher insects will be able

to recall examples of the value of such fixed behaviour patterns in

classification. [12]

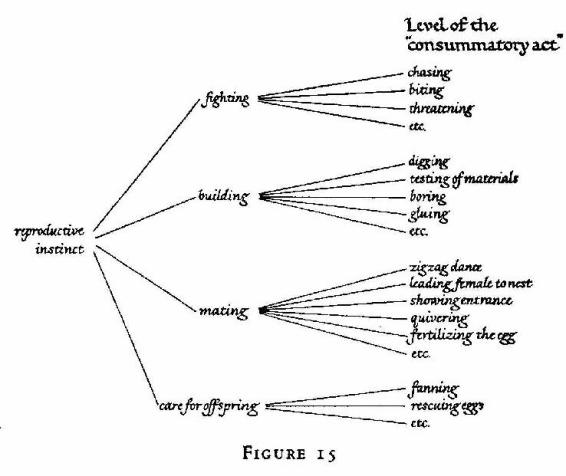

of fixed action-patterns, which incorporate the rules of the game of

courting, nest-building, duelling, etc. Each of these activities is again

a hierarchy of autonomous sub-skills. These tend to be more flexible

on the higher levels which co-ordinate the drive, and more rigid on the

lower levels. The autonomous sub-codes are restrained from spontaneous

activity by 'inhibitory blocks', and triggered into activity by patterned

impulses from higher echelons. This trigger-sensitive apparatus is called,

after Lorenz, the "innate releasing mechanism" -- or I.R.M. for short:

In all the channels which flow downward from the centre [of a given

drive], there is supposed to exist a physiological mechanism which

effectively prevents all discharge of activity unless the animal

encounters the right environmental situation and stimuli to remove

or release this block. Thus there is an innate releasing mechanism

(I.R.M.) . . . which is in some way attuned to the biologically right

stimulus in the environment . . . and which is, as it were, unlocked

by the appropriate releaser, thus allowing behaviour to proceed to the

next lower level. These in their turn incorporate blocks and, so long

as these remain, action of these lower centres cannot proceed.' [13]

is the reproductive behaviour of the male stickleback, which I shall

describe in the terminology of the present theory.

code', while hormonal activities provide the drive or motivation. The

fish then migrates into shallow water and swims around until a certain

environmental configuration (rise of temperature, combined with green

vegetation, etc.) strikes the 'right note', i.e. releases an efferent

impulse, which in turn triggers off the sub-code of the nest-building

activity. This activity is again subdivided into digging, glueing, etc.,

each of these skills governed by its autonomous sub-code. The latter are

activated by trigger releasers; the order of operations is determined by

inputs from the environment and proprioceptive feedbacks. The hierarchy of

mating behaviour remains blocked until nest-building is complete; but the

'fighting' hierarchy (with its five different sub-codes) may be called

at any moment into action by a trigger mechanism sensitive to a specific

sign-Gestalt input: 'red male entering territory'. In this case the

fighting code dominates the animal's entire behaviour, and nest-building

as well as other activities are inhibited while the emergency lasts:

the (functional) part monopolizes the attention of the whole.

The sub-units of the behaviour-pattern tend to become more specific

regarding input and more stereotyped in output on the lower levels of

the hierarchy. 'Which one of the five motor responses belonging to the

fighting pattern will be shown depends on sign stimuli that are still more

restricted in effect.' [14] The nuptial colours of the fish are shining

blue eyes and a red underbelly. Accordingly, any crude model which is

red underneath will release an attack, regardless of shape and size --

whereas a perfectly shaped model without nuptial colouring will not

do so. Apart from colour, behaviour also acts as a releaser. 'When the

stranger bites, the owner of the territory will bite in return. When the

stranger threatens, the owner will threaten back; when the stranger flees,

the owner will chase it; and so on. . . . [15] But fighting is rarer than

threat. The threat-behaviour of male sticklebacks is peculiar. Not only do

they dart towards the opponent with raised dorsal spines and open mouth,

ready to bite, but, when the opponent does not flee at once but resists,

the owner of the territory does not actually bite but points its head

down and, standing vertically in the water, makes some jerky movements

as if it were going to bore its snout into the sand. [16]

This of course is an exceptional example -- nest-building is a rarity

among fish. But the rigidity of fixed action patterns in certain

classes -- such as birds and insects -- remains nevertheless a striking

phenomenon. The ritualized rules of the game of courtship and display,

of threat and danger signals, of tournament fighting and social behaviour,

sometimes reminds one of the ceremonious observances at Byzantine courts,

at other times of the obsessive rituals of compulsion-neurotics. And

the process of 'ritualization' does indeed suggest the 'emancipation'

-- or isolation -- of a behaviour-pattern from its original context,

accompanied by intensification, stabilization, and rhythmic repetitiveness

of the pattern; the reasons are as yet hardly understood. [17]

Appetitive Behaviour and Consummatory Act

In spite of the relatively stereotyped nature of fixed action-patterns --

of which ritualization is an extreme example -- it would be entirely

wrong to regard the hierarchy of instinct behaviour as a one-way

affair, in which a plastic, general drive (the 'appetitive behaviour')

discharges downward along pre-formed and discrete alternative channels

into the completely rigid and mechanical, fixed-action-patterns of the

'consummatory act'. This conception of the organism as an automaton whose

'adaptability' is reduced to that of a kind of automatic record-changer

or jukebox, with a choice between a few dozen fixed records appropriate

to the occasion, seems to have originated in a misunderstanding of the

distinction made by Wallace Craig between 'appetitive behaviour' and

'consummatory act'. This point must be briefly discussed as it is of

some importance for the sections which follow.

Appetite (or 'appetance') was defined by Craig (1918) as a 'state of

agitation', a striving for an absent 'appeted' stimulus (conversely,

a striving to escape from a noxious or disturbing stimulus); whereas the

'cousummatory act' was meant to bring the activity to a close by attaining

(or escaping from) the appetitive stimulus, 'after which the appetitive

behaviour ceases and is succeeded by a state of relative rest'. [18]

More generally, 'the term appetitive behaviour is used by present-day

writers on ethology to mean the flexible or variable introductory phase

of an instinctive behaviour pattern or sequence'. [19]

Thus 'appetitive behaviour' became a more refined and noncommittal name

for the old, shop-soiled concepts of 'need', 'drive', 'instinct', and

'purpose'.* So far all was well; it was the 'consummatory act', which

led instinct-theory into a cul-de-sac. The trouble started, rather

inconspicuously, when first Woodworth [20] then, independently from

each other, K. S. Lashley and Konrad Lorenz became impressed with the

stereotyped character of certain 'consummatory acts' (animal rituals

and automatized habits in humans), as compared with the more general

'appetitive behaviour' or drive.** Eventually the focussing of attention

on such fixed patterns of behaviour led to a distortion of the whole

picture: Lorenz and Tinbergen made a rigid distinction between appetitive

behaviour which was supposed to be flexible, and consummatory acts which

were supposed to be completely fixed and automatic. Thus Tinbergen:

It will be clear, therefore, that this distinction between appetitiveBut what exactly, one might ask, constitutes a 'consummatory act'?

behaviour and consummatory act separates the behaviour as a whole into

two components of entirely different character. The consummatory

act is relatively simple; at its most complex it is a chain of

reactions. . . . But appetitive behaviour is a true purposive activity,

offering all the problems of plasticity, adaptiveness, and of complex

integration that baffle the scientist in his study of behaviour as

a whole. . . . Lorenz has pointed out . . . that purposiveness, the

striving towards an end, is typical only of appetitive behaviour and

not of consummatory actions. . . . Whereas the consummatory act seems

to be dependent on the centres of the lowest level of instinctive

behaviour, appetitive behaviour may be activated by centres of all

the levels above that of the consummatory act. . . . [21] The centres

of the higher levels do control purposive behaviour which is adaptive

with regard to the mechanisms it employs to attain the end. The lower

levels, however, give rise to increasingly simple and more stereotyped

movements, until at the level of the consummatory act we have to do

with an entirely rigid component, the taxis, the variability of which,

however, is entirely dependent on changes in the outer world. This

seems to settle the controversy; the consummatory act is rigid, the

higher patterns are purposive and adaptive. [22]

A glance at Tinbergen's diagram on

Other books

Katy's Men by Carr, Irene

02 Thunder of Heaven: A Joshua Jordan Novel by Tim Lahaye

Khyber Run by Amber Green

The Dark Clue by James Wilson

Latimer's Law by Mel Sterling

Creatus (Creatus Series) by Carmen DeSousa

Winning Her Over by Alexa Rowan

Silt, Denver Cereal Volume 8 by Claudia Hall Christian

The Troubled Air by Irwin Shaw

Tales of the Djinn: The Double by Emma Holly