The 9/11 Wars (86 page)

Authors: Jason Burke

Tags: #Political Freedom & Security, #21st Century, #General, #United States, #Political Science, #Terrorism, #History

The cumulative total of dead and wounded in this conflict so far is substantial. Any estimates of casualties in such a diverse and complex conflict is necessarily very approximate, but some idea of its human cost can be obtained nonetheless. The military dead are the best documented. Though some may have shown genuine enthusiasm for war or even evidence of sadism,

9

many Western soldiers did not enlist with the primary motive of fighting and killing others. A significant number came from poor towns in the Midwest of America or council estates in the UK and had joined up for a job, for adventure, to pay their way through college, to learn a craft. By the end of November 2010, the total of American soldiers who had died in Operation Iraqi Freedom and its successor, Operation New Dawn, was 4,409, with 31,395 wounded in action.

10

More than 300 servicemen from other nations had been killed too and many more maimed, disabled or psychologically injured for life. In Afghanistan, well over 2,000 soldiers from 48 different countries had been killed in the first nine years of the Afghan conflict. These included 1,300 Americans, 340 Britons, 153 Canadians, 49 Frenchmen and 44 Germans.

11

Military casualties among Western nations – predominantly American – in other theatres of Operation Enduring Freedom from the Sudan to the Seychelles and from Tajikistan to Turkey added another 100 or so. At least 1,500 private contractors died in Iraq alone.

12

Then there were the casualties sustained by local security forces. Around 12,000 police were killed in Iraq between 2003 and 2010.

13

In Afghanistan, the number of dead policemen since 2002 had exceeded 3,000 by the middle of 2010.

14

Many might have been venal, brutal and corrupt, but almost every dead Afghan policeman left a widow and children in a land where bereavement leads often to destitution. In Pakistan, somewhere between 2,000 and 4,000 policemen have died in bombing or shooting attacks.

15

As for local militaries in the various theatres of conflict, there were up to 8,000 Iraqi combat deaths in the 2003 war, and another 3,000 Iraqi soldiers are thought to have died over the subsequent years.

16

In Afghanistan, Afghan National Army casualties were running at 2,820 in August 2010, while in Pakistan, around 3,000 soldiers have been killed and at least twice as many wounded in the various campaigns internally since 2001.

17

Across the Middle East and further afield in the other theatres that had become part of the 9/11 Wars, local security forces paid a heavy price too. More than 150 Lebanese soldiers were killed fighting against radical ‘al-Qaeda-ist’ militants in the Nahr al-Bared refugee camp in Lebanon in 2007, for example. There were many others, in Saudi Arabia, in Algeria, in Indonesia. In all, adding these totals together, at least 40,000 or 50,000 soldiers and policemen have so far died in the 9/11 Wars. Casualties among their enemies – the insurgents or the extremists – are clearly harder to establish. Successive Western commanders said that they did not ‘do body counts’, but most units kept a track of how many casualties they believed they had inflicted, and these totals were often high. At least 20,000 insurgents were probably killed in Iraq, roughly the same number in Pakistan, possibly more in Afghanistan.

18

In all that makes at least 60,000 people, again many with wives and children.

Then, of course, there are those, neither insurgent nor soldier, neither terrorist nor policeman, who were caught in a war in which civilians were not just features of the ‘battle space’ but very often targets. In 2001, there were the 9/11 attacks themselves, of course, with their near 3,000 dead. In 2002 alone, at least 1,000 people died in attacks organized or inspired by al-Qaeda in Tunisia, Indonesia, Turkey and elsewhere. The casualties from such strikes continued to mount through the middle years of the decade. One study estimates 3,013 dead in around 330 attacks between 2004 and 2008.

19

By the end of the first ten years of the 9/11 Wars, the total of civilians killed in terrorist actions directly linked to the group or affiliated or inspired Islamic militants was almost certainly in excess of 10,000, probably nearer 15,000, possibly up to 20,000. To this total must be added the cost to civilians of the central battles of the 9/11 Wars. In Iraq generally, estimates vary, but a very conservative count puts violent civilian deaths (excluding police) from the eve of the invasion of 2003 to the end of 2010 at between 65,000 and 125,000.

20

They included more than 400 assassinated Iraqi academics and almost 150 journalists killed on assignment.

21

The true number may be many times greater. In Afghanistan, from October 7, 2001, the day when the bombing started, to mid October 2003, between 3,000 and 3,600 civilians were killed just by coalition air strikes.

22

Many more have died in other ‘collateral damage’ incidents or through the actions of the insurgents. The toll has steadily risen. In 2005, the total was probably around 450 civilian casualties. From 2006 to 2009 between 5,000 and 7,000 civilian deaths were documented, depending on the source. In 2010 alone, 2,777 died, mostly due to insurgent action. Half as many again had already died by mid May 2011. In all, between 14,000 and 17,000 civilians have been killed in Afghanistan, and at least three or four times that number wounded or permanently disabled. In Pakistan, which saw the first deaths outside America of the 9/11 Wars, the number of casualties since that first handful died when police shot into demonstrations in October 2001 are estimated by local authorities and regional analysts at around 9,000 dead and between 10,000 and 15,000 injured.

23

Add these admittedly rough figures from the principal theatres of the Wars together and you reach a total of well over 150,000 civilians killed. In all the approximate overall figure for civilian and military dead of the violence associated with the 9/11 Wars is probably near 250,000. If the injured are included – even at a conservative ratio of one to three – the total number of casualties reaches 750,000. This may be a sum that is lower than the losses inflicted on combatants and non-combatants during the murderous major conflicts of the twentieth century but still constitutes a very large number of people. Add the bereaved and the displaced,

24

let alone those who have been harmed through the indirect effects of the conflict, the infant mortality or malnutrition rates due to breakdown of basic services, and the scale of the violence that we have witnessed over the last years is clear. The changes in our lives and societies will be commensurate. Some day this conflict – the 9/11 Wars – will be remembered by another name. Most of the dead will not be remembered at all.

ALI SHAH

At 11 o’clock a cold, hard wind cut across the frozen mud and dry grass of a patch of wasteland hidden by a thick line of gorse and brush behind a lay-by a few hundred metres from the outer perimeter fences of the northern French port of Dunkirk. Among the bushes, a hundred or so young men had built makeshift shelters. It was a week or so since the local police had come by with bulldozers, and the shelters, rebuilt after each such raid, were crowded. Under the wood stripped from nearby trees, plastic sheeting handed out by local campaigners, dustbin bags, salvaged sheets of rusted corrugated iron, blankets and the occasional upturned shopping trolley, groups of young men huddled around fires. Above, gulls circled and shrieked in the grey winter sky.

Kurds and Arabs from Iraq, a handful of Somalians, a smattering of Iranians, a few dozen Afghans, two Syrians, an Algerian and a Pakistani, they came from almost every theatre touched by the 9/11 Wars. Among them was a twenty-four-year-old Hazaran Afghan with a thin beard, worn jeans and a cheap red ski jacket pulled tight over a thin cotton sweater. This was Ali Shah, the young shepherd with a taste for learning English who had escaped from Bamiyan over the mountain trails at night as the Taliban had prepared to destroy the Buddhas all those years before. Ali Shah had eventually made his way to Iran and had watched the news of the 9/11 attacks in a café near the eastern Iranian city of Mashhad, where he worked as a mechanic’s assistant. In 2003, after briefly being jailed, he had returned to Afghanistan to find his family in Kabul, where he was hired by an international NGO as a driver. He earned good money until repeated threats from insurgent sympathizers forced him to flee. Having decided to try his luck in Europe, Ali Shah set his sights on the UK. His savings were enough to pay the traffickers. Old friends looked after him on his way through Iran. He had trekked over the Iranian–Turkish frontier, hitchhiked to Istanbul and then paid $3,000 to get to Greece before spending almost all his remaining money – $1,400 – to be brought by boat to Italy. He had taken a train from Milan to Paris, slept in a park for a week near the Gare de l’Est and then taken a train to Calais. Almost picked up by the police there, he had managed to slip away through undergrowth before hitching north to Dunkirk, where he had heard things were better. Now he was stuck again. Every night he tried to get into trucks heading for the UK but without success. He had no money and relied on sympathetic locals for food and firewood. ‘I have been travelling for too long. I would like to go home, but the situation in Afghanistan is very bad,’ he said and looked towards the lines of trucks parked in the dusk beside the port. ‘Hopefully things will be better when I get to the other side. I am now very tired.’

25

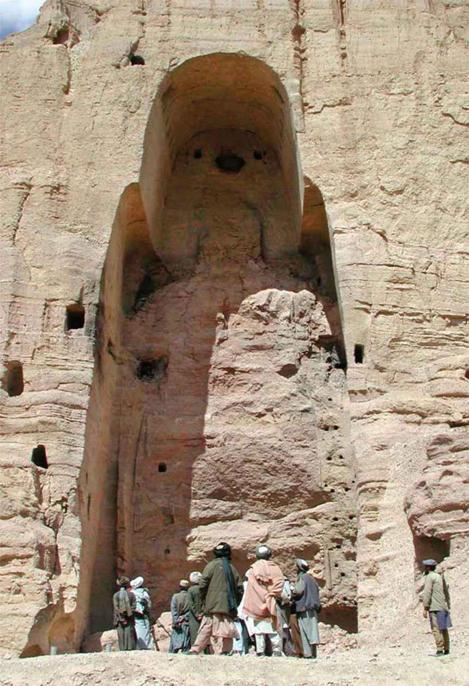

1. Bamiyan, Afghanistan. The Taliban’s destruction of the ancient statues of Buddha in March 2001 was not simple fanaticism but a carefully judged act of spectacular violence designed to send a message to various local and international audiences and thus a sign of what was to come.

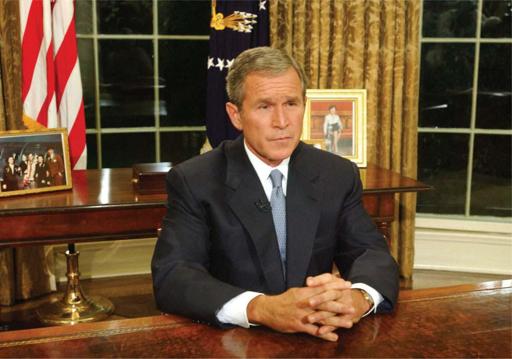

2. The folksy language and faith of George W. Bush connected with Middle America – whatever people thought overseas. The forty-third US president remained committed to a radical and ideological foreign policy throughout his time in office. In his memoirs, he said history would vindicate his decisions.

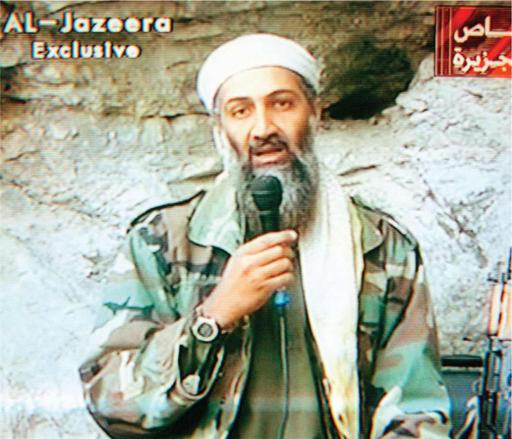

3. The key aim of Saudi Arabian-born Osama bin Laden was to radicalize the world’s 1.2 billion Muslims and thus mobilize them to revive their faith and fight ‘injustice’, tyranny and the West. But his ideology – a selective mix of politics, religion and myth – showed little respect for local cultural differences or identities and eventually failed to attract mass support.