The $100 Startup: Reinvent the Way You Make a Living, Do What You Love, and Create a New Future (34 page)

Authors: Chris Guillebeau

Health Insurance

In the United States, it’s the big question facing many prospective entrepreneurs: “How can I insure my family when I’m self-employed?” (Canadians and others can skip this section and breathe easy.) Unfortunately, universal health care is still a long way off before we catch up with the rest of the developed world.

To get some options, I surveyed our group of case studies (those from the U.S.) and also conducted several online conversations with large groups on Twitter and Facebook. The answers varied considerably. Someone wrote, “Get screwed and pay a lot of money for coverage that doesn’t help you.” Alas, in some cases, that statement may not be much of a stretch. But in other cases you have choices. Here are some of the most common ones.

Buy a high-deductible policy and pay cash for visits to the doctor

. Perhaps the most common solution among the self-employed is to shop around and purchase a high-deductible policy to cover serious illness or accident. Then set aside a savings fund—either self-managed or with a health savings account (HSA)—to cover doctor’s visits and preventive care. It’s best to compare quotes from an independent broker, and in some cases a local or national group may offer a discounted policy. Several people mentioned the Freelancers Union, for example.

†

Join a concierge program

. A concierge program is the opposite of a high-deductible policy that covers only serious problems. For a monthly fee ($150 to 300 on average), you can visit the same doctor for most primary and preventive needs. You’ll also get the doctor’s email address and “call anytime” cell phone number, and the doctor will act as an

advocate and referrer if you need more serious care. Some people combine a concierge program with another policy to ensure that both short-term and disaster prevention needs are met.

Get insured through your partner

. A number of business owners wrote to tell me that they relied on their spouse or partner’s job to cover both of them while they worked full-time or part-time in the business. Courtney Carver was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis in 2006, and her medical bills would be $8,000 a month without insurance. “I feel fortunate that my husband works for a company that has group insurance,” she says. “For now, starting a business together with him leaving his job is not an option because of my medical condition. We are looking at other out-of-state options for the future but are tied to his job for the insurance for now.”

Of course, this option isn’t available to you if you’re single or if your partner doesn’t have a job that provides insurance benefits, but if you do have the option, it may very well be the best one.

Stay on COBRA as long as possible

. If you have lost your job, COBRA allows you to continue receiving the same health-care coverage for a certain length of time at the same price your former employer paid. You have to pay for it, but because it originally was based on a group rate, the cost is often lower (and coverage may be better) than that of any plan you could purchase yourself. Several people spoke of extending COBRA coverage for up to three years as they built their businesses.

Self-insure or use an HSA

. “My health-care plan involves prayer, vitamins, and avoiding sharp objects,” Amy Oscar told me on Twitter. Others explained that they were just being pragmatic about the poor options available to them, weighing the costs and what they perceived as limited benefits of an expensive plan they weren’t likely to use. If you have a family or health-care issues, you may not be comfortable with this option.

PRICING REVIEW

.

As discussed in

Chapter 11

, you should review your prices regularly to determine whether a price increase is in order. In addition, consider adding appropriate upsells, cross-sells, or other income-generating tools to your arsenal.

CUSTOMER COMMUNICATION

.

This involves not just dealing with emails or general inquiries, but initiating communication through newsletters and updates.

A key rule for all these activities is to initiate, not respond. Doing this for just forty-five minutes a day can bring huge rewards even when everything else is crazy and you spend the rest of the day putting out fires. Onward!

Regardless of your growth strategy, you’ll want to pay attention to the health of your business. The best way to do this is with a two-pronged strategy:

Step 1: Select one or two metrics and be aware of them at any given time, focusing on sales, cash flow, or incoming leads.

Step 2: Leave everything else for a biweekly or monthly review where you delve into the overall business more carefully.

Some members of our group were much more diligent about tracking metrics than others, with a number of people talking about being obsessive over data and others saying they had “no idea”

about what was happening in the business. (My opinion on this approach: Personalities and skill sets vary, but be wary of delegating all financial knowledge to someone else. Having no idea about money stuff is usually a bad sign.)

The metrics you want to track will vary with the kind of business. Here are a few of the most common examples.

Sales per day:

How much money is coming in?

Visitors or leads per day:

How many people are stopping by to take a look or signing up for more information?

Average order price:

How much are people spending when they order?

Sales conversion rate:

What percentage of visitors or leads become customers?

Net promoter score:

What percentage of customers would refer your business to someone else?

Some businesses choose more specific metrics. Brandy Agerbeck, the graphic facilitator we met in

Chapter 7

, earns her living through corporate and non-profit bookings. Every year she needs a certain amount of bookings, so she keeps a set of index cards to track this number. When the index cards fill up, she knows she’s good for a while and can focus on other things.

Once or twice a month it’s good to take a deeper look at the business and record some metrics that should be improving over time. The kinds of things you’ll probably be interested in are more detailed sales figures, site traffic and social media, and the growth of the business. You can get a free spreadsheet to help with this process in the online resources for this book at

100startup.com

.

Really

Long

John Warrillow built and sold four companies before “retiring” to write, speak, and invest. After learning his lessons through those four experiences, he now advocates a specific model for owners of small companies who wish to sell their business one day. Most of John’s recommendations relate to the need to create an actual company or organization that can thrive outside the business owners’ specific skills.

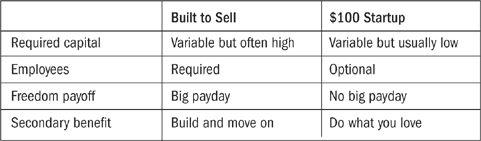

In other words, the built-to-sell model is different from the model we’ve looked at in this book. Many of our case studies involve people who went into business for themselves because it was fun, not because they wanted to build something and then cash out. However, John’s recommendations are solid for owners who want to pass a business on, and some of them can be adapted to improve a business even if you want to stick around. You can see how the two models compare in the table below.

BUILT TO SELL—$100 STARTUP COMPARISON

In trying to decide which path to pursue, the simple question to answer is: “What kind of freedom do you want?” John’s model is all about creating an entity apart from yourself and then selling it for a big payday. The $100 Startup model is more about transitioning to a business or independent career that is based on something you love to do—in other words, something intrinsically related to the

owner’s skill or passion. Neither model is better; it just depends on your goals.

If you’d like to have the option of selling your business one day, John’s point is that you have to plan for it by taking specific steps. The most important step in creating an independent identity for the business is to create a product or service with the potential to scale. This is an important distinction from many of the businesses we’ve described thus far, so let’s take a look at how John explains it.

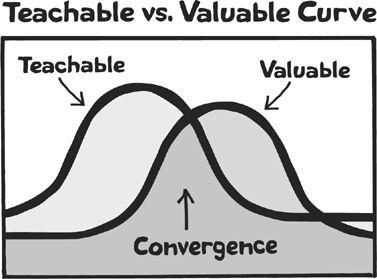

A scalable business is built on something that is both teachable and valuable. A CPA provides a highly valuable service, but it isn’t easily teachable (she can’t just bring someone into her practice and hand it over to him). On the other hand, you can teach someone how to bus tables at a restaurant in a few minutes, but that isn’t a valuable service (lots of people can bus tables). Therefore, a business that has the potential to be sold easily for a high profit offers something at the intersection of teachable and valuable.

John built a subscription service that conducted financial research and provided a series of informative reports. This was

highly valuable to his clients but also teachable to other employees. Another time he built a firm that produced consumer focus groups for big companies—again, a highly valuable service, but also replicable under new ownership.

The solutions found by Tsilli, Cherie, Tom, Jessica, and John varied considerably. In implementing their solutions, each of them said yes to something while saying no to something else. Tom declined to accept the deals from big-box retailers, but he wasn’t afraid to hire employees and grow on his own terms. Cherie preferred to keep things small and intimate. Tsilli found security by growing her business

and

working as a contractor for her former employer.

What united these different experiences was a sense of controlling their own destiny and finding freedom in nurturing a meaningful project. As your own project grows, you’ll also need to make decisions based on your preferences and specific vision. Just remember that these are good decisions to make and a good position to be in.

KEY POINTS

There’s more than one road to freedom, and some people find it through a combination of different working arrangements.

“Going long” by pursuing growth and deciding to stay small are both acceptable options, and you can split the difference by “going medium.” It all depends on what kind of freedom you’d like to achieve.

Work “on” your business by devoting time every day to activities specifically related to improvement, not just by responding to everything else that is happening.

Regularly monitor one or two key metrics that are the lifeblood of your business. Check up on the others monthly or bimonthly.

A business that is scalable is both teachable and valuable. If you ever want to sell your business, you’ll need to build teams and reduce owner dependency.