Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh (29 page)

Read Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh Online

Authors: John Lahr

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Literary

BOOK: Tennessee Williams: Mad Pilgrimage of the Flesh

12.35Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Back on native ground, Merlo found himself with full days; he was in charge of the house, the food, and the eccentric Reverend Dakin. “Grandfather is having the time of his life,” Williams wrote to Margo Jones. “He’s crazy about Frankie who drives him around everywhere that he takes a notion to go, and he usually has a notion to go somewhere.” In St. Louis, where he lived in a room in Edwina’s house, the Reverend felt confused and marginalized. (Insisting that her father was only “pretending to be deaf,” Edwina refused to repeat anything that he didn’t hear.) In his makeshift Key West family, Reverend Dakin was an honored guest, at the center of things. “Tom is so good to me,” he wrote to Wood. “I love him.” While Merlo and the Reverend ventured out by car most mornings, Williams typed away at the dining-room table, gradually converting the strangulated “Stornello” into the rich comic lyricism of

The Rose Tattoo

. In the afternoons, the ménage decamped to the beach. “A girl makes her best contacts in the afternoon when she can see what she’s doing,” Williams joked.

The Rose Tattoo

. In the afternoons, the ménage decamped to the beach. “A girl makes her best contacts in the afternoon when she can see what she’s doing,” Williams joked.

“I feel somewhat rejuvenated and moderately at peace for the first time in perhaps three years,” he wrote to Jones in the first days of the new ecade. Even his alcohol intake was down to “five drinks a day,” he crowed to the bibulous Carson McCullers. When Merlo went north for Christmas, intending, among many other treats, to visit Carson McCullers and see her Broadway hit

The Member of the Wedding

, Williams wrote ahead to her. “He will bring you good-luck as he has me,” he said. Merlo returned on January 5, 1950, bearing Christmas presents for Williams—records, cologne, and a gold snake ring with little diamond chips, “the nicest piece of jewelry I have owned.” “Frankie had lost weight at home and seemed glad to be back in our peaceful little world,” Williams said. It was true: for Merlo, too, these gracious days felt like a blessing. “We shall all be together again soon in the house we love so much,” Merlo wrote later to the Reverend Dakin, from Rome, in July 1950. “God has been very good to us this year, dear friend, when we think how much happiness and good fortune these past few months (and coming ones, too) contained.”

The Member of the Wedding

, Williams wrote ahead to her. “He will bring you good-luck as he has me,” he said. Merlo returned on January 5, 1950, bearing Christmas presents for Williams—records, cologne, and a gold snake ring with little diamond chips, “the nicest piece of jewelry I have owned.” “Frankie had lost weight at home and seemed glad to be back in our peaceful little world,” Williams said. It was true: for Merlo, too, these gracious days felt like a blessing. “We shall all be together again soon in the house we love so much,” Merlo wrote later to the Reverend Dakin, from Rome, in July 1950. “God has been very good to us this year, dear friend, when we think how much happiness and good fortune these past few months (and coming ones, too) contained.”

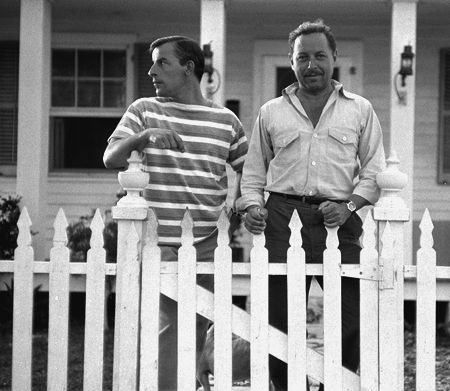

With Merlo outside Key West house, 1957

By December 4, 1949, Williams had completed a “kitchen sink version” of

The Rose Tattoo

. The story celebrated his deliverance from a creative and emotional stalemate. Inevitably, as Williams’s bond with Merlo solidified, the landscape of his play took on deeper coloration; he compared it to a “dark, blood-red translucent stone that is twisted this way and that, to give off its somber rich light.” When he submitted the play to Kazan in June 1950, the light-dark theme was a defining part of his pitch. “During the past two years I have been, for the first time in my life, happy and at home with someone and I think of this play as a monument to that happiness, a house built of images and words for that happiness to live in,” he wrote. “But in that happiness there is the long, inescapable heritage of the painful and the perplexed like the dark corners of a big room.”

The Rose Tattoo

. The story celebrated his deliverance from a creative and emotional stalemate. Inevitably, as Williams’s bond with Merlo solidified, the landscape of his play took on deeper coloration; he compared it to a “dark, blood-red translucent stone that is twisted this way and that, to give off its somber rich light.” When he submitted the play to Kazan in June 1950, the light-dark theme was a defining part of his pitch. “During the past two years I have been, for the first time in my life, happy and at home with someone and I think of this play as a monument to that happiness, a house built of images and words for that happiness to live in,” he wrote. “But in that happiness there is the long, inescapable heritage of the painful and the perplexed like the dark corners of a big room.”

For

The Rose Tattoo

, Umberto, the improbable figure who lures the widow away from her ascetic resignation and back into life, was rechristened Alvaro Mangiacavallo (“eat a horse”), a surname that incorporated Williams’s nickname for Merlo and made him central to the widow’s erotic excitement, just as “Little Horse” was central to Williams’s own yearning. When Alvaro makes a phone call, on behalf of the widow, to identify Rosario’s inamorata, he says, “Well, this is your little friend, Alvaro Merlo, speaking!” Alvaro was constructed more or less to Merlo’s proportions: “one of those Mediterranean types that resemble glossy young bulls . . . short in stature, has a massively sculptural torso. . . . There is a startling, improvised air about him,” the stage directions read. The plump and hysterical widow is a medley of vulnerabilities and vainglories—“the Baronessa,” as the community teasingly nicknames her—an outline into which Williams could insert his own porous, crying-out heart. The struggle she faces—between the pleasures of renunciation and of connection—was also dramatized in “Humble Star,” a poem Williams wrote just after completing the first draft of

Rose Tattoo

and dedicated to Merlo:

The Rose Tattoo

, Umberto, the improbable figure who lures the widow away from her ascetic resignation and back into life, was rechristened Alvaro Mangiacavallo (“eat a horse”), a surname that incorporated Williams’s nickname for Merlo and made him central to the widow’s erotic excitement, just as “Little Horse” was central to Williams’s own yearning. When Alvaro makes a phone call, on behalf of the widow, to identify Rosario’s inamorata, he says, “Well, this is your little friend, Alvaro Merlo, speaking!” Alvaro was constructed more or less to Merlo’s proportions: “one of those Mediterranean types that resemble glossy young bulls . . . short in stature, has a massively sculptural torso. . . . There is a startling, improvised air about him,” the stage directions read. The plump and hysterical widow is a medley of vulnerabilities and vainglories—“the Baronessa,” as the community teasingly nicknames her—an outline into which Williams could insert his own porous, crying-out heart. The struggle she faces—between the pleasures of renunciation and of connection—was also dramatized in “Humble Star,” a poem Williams wrote just after completing the first draft of

Rose Tattoo

and dedicated to Merlo:

Death is high.

It is where the green-pointed things are.

I know, for I left on the wings of it.

While you slept, breathlessness took me

to a green-pointed star.

I was exalted but not at ease

in the space.

Beneath me your breathing face

cried out, Return, return!

Return, you called while you slept.

And desperately back I crept

against the vertical fall.

It was not easy to crawl

against those unending torrents

of light, all bending one way,

And only your voice calling, Stay!

But my longing was great

to be comforted and warmed

Once more by your sleeping form,

to remain, yet a while, no higher

than where you are,

Little room, warm love, humble star!

Williams honored Merlo’s inspiration in another significant way: he gave him a percentage of the play. “I want him to feel some independence,” Williams told Wood in March. “His position with me now lacks the security and dignity that his character calls for.” Intimacy required equality; the money went some way to ensuring it.

The Rose Tattoo

was also dedicated to Merlo “in return for Sicily”; the exchange to which the play was a testament, however, was as much psychological as geographical. Even before Williams had written about Sicily or visited it, his identification with the place and with Merlo’s stories about it signaled a hysteric’s desire to merge with the alluring personality of his friend. Merlo regaled Williams with tales of his parents, originally from Ribera, and their large, noisy, bumptious first-generation Sicilian-American family. According to Merlo, sometimes after a family blowup, his mother would take umbrage in the garden and climb into a fig tree to sulk. “I remember Frankie telling us that after one particularly blinding row, she refused to come down,” Maria Britneva recalled. “Having shouted at her, and pleaded with her, her sons eventually took an axe to the tree and brought the whole thing down, with her in it.” Britneva went on, “Tennessee and I . . . were whimpering with laughter. Frankie was livid.”

The Rose Tattoo

was also dedicated to Merlo “in return for Sicily”; the exchange to which the play was a testament, however, was as much psychological as geographical. Even before Williams had written about Sicily or visited it, his identification with the place and with Merlo’s stories about it signaled a hysteric’s desire to merge with the alluring personality of his friend. Merlo regaled Williams with tales of his parents, originally from Ribera, and their large, noisy, bumptious first-generation Sicilian-American family. According to Merlo, sometimes after a family blowup, his mother would take umbrage in the garden and climb into a fig tree to sulk. “I remember Frankie telling us that after one particularly blinding row, she refused to come down,” Maria Britneva recalled. “Having shouted at her, and pleaded with her, her sons eventually took an axe to the tree and brought the whole thing down, with her in it.” Britneva went on, “Tennessee and I . . . were whimpering with laughter. Frankie was livid.”

Merlo’s tales of his Sicilian community—with its aggressions and repressions, its emotional extravagance—excited Williams’s imagination and suited his rhythm. “My approach to my work is hysterical,” he told Kazan. “It is infatuated and sometimes downright silly. I don’t know what it is to take anything calmly.” The Sicilian response to life was also histrionic; it turned feeling into event. “Have I ever told you that I like Italians?” Williams wrote to Britneva from Rome in 1949. “They are the last of the beautiful young comedians of the world.” He went on, “The Young Horse . . . has returned from Sicily where he had a case of galloping dysentery. . . . He said it was the goat’s milk that did it. They brought the goat right into his bedroom and milked it beside the bed and handed him the milk and would not take no for an answer as the goat was a great prize. Soon as he has recovered sufficiently, and he is showing some signs of recovery now, we are going back down there together in the Buick. As I am too fat, the goat will do me no harm, and the reports of social life down there are fantastic. The girls are not allowed to speak to the boys till after marriage: a kiss has the same consequences as a pregnancy used to have in the backward communities of the South, and they must still have dowries, no matter how pretty.” (A goat appears in

The Rose Tattoo

as an emblem of the play’s lyric spirit—“the Dionysian element in human life, its mystery, its beauty, its significance.”)

The Rose Tattoo

as an emblem of the play’s lyric spirit—“the Dionysian element in human life, its mystery, its beauty, its significance.”)

The Rose Tattoo

’s Sicilian-American locale “somewhere along the Gulf Coast” also strategically allowed Williams to depart from the familiar topography of the South, as well as from the tropes of Southern character, caste, and speech that threatened to stereotype his work. A “giant step forward,” Wood called

The Rose Tattoo

, even before she approved of the play. But Williams’s personal breakthrough was even more significant than his stylistic one: his guarded self had surrendered to another.

The Rose Tattoo

tried to capture the perplexity of this connection—“the baffled look, the stammered speech, the incomplete gesture, the wild rush of beings past and among each other.”

’s Sicilian-American locale “somewhere along the Gulf Coast” also strategically allowed Williams to depart from the familiar topography of the South, as well as from the tropes of Southern character, caste, and speech that threatened to stereotype his work. A “giant step forward,” Wood called

The Rose Tattoo

, even before she approved of the play. But Williams’s personal breakthrough was even more significant than his stylistic one: his guarded self had surrendered to another.

The Rose Tattoo

tried to capture the perplexity of this connection—“the baffled look, the stammered speech, the incomplete gesture, the wild rush of beings past and among each other.”

HAVING LABORED SO fiercely to finish

The Rose Tattoo

and to get it to Wood before the New Year, Williams found her silence deafening. By the end of January, feeling “tentative and mixed,” afraid even to re-read his play, he finally cabled Wood for a response. Wood immediately wired back that she was “very optimistic and thought it had the making of a great commercial vehicle.” Williams saw through her well-chosen words, which made him feel “that the script might be something to pretend had not happened like public vomiting.”

The Rose Tattoo

and to get it to Wood before the New Year, Williams found her silence deafening. By the end of January, feeling “tentative and mixed,” afraid even to re-read his play, he finally cabled Wood for a response. Wood immediately wired back that she was “very optimistic and thought it had the making of a great commercial vehicle.” Williams saw through her well-chosen words, which made him feel “that the script might be something to pretend had not happened like public vomiting.”

Meanwhile, word of the play was leaking out. On January 22, Irene Selznick called Key West asking to read it. “I said I was still too nervous,” Williams told Wood. To Bigelow, he worried as he awaited more word from Wood: “The play is probably too subjective, an attempt to externalize an experience which was too much my own.” To Gore Vidal, he bitched, “Audrey is sitting on the new script like an old hen.”

In late February, Williams finally got an enthusiastic response from Kazan, who was already in pre-production with the screen version of

A Streetcar Named Desire

. “It is a kind of comic-grotesque Mass said in praise of the Male Force,” Kazan wrote—a description so apt that Williams himself later adopted it. “Your letter about the play makes it possible for me to go on with it,” Williams replied. “I think you see the play more clearly than I did. I have this creative will tearing and fighting to get out and sometimes the violence of it makes its own block. I don’t stop to analyze much. I guess I don’t dare to. I am afraid it would go up in smoke. So I just attack, attack, like the goat—but with less arrogance and power!” He went on, “You have a passion for organization, for seeing things in sharp focus which I don’t have and which makes our combination a good one.”

A Streetcar Named Desire

. “It is a kind of comic-grotesque Mass said in praise of the Male Force,” Kazan wrote—a description so apt that Williams himself later adopted it. “Your letter about the play makes it possible for me to go on with it,” Williams replied. “I think you see the play more clearly than I did. I have this creative will tearing and fighting to get out and sometimes the violence of it makes its own block. I don’t stop to analyze much. I guess I don’t dare to. I am afraid it would go up in smoke. So I just attack, attack, like the goat—but with less arrogance and power!” He went on, “You have a passion for organization, for seeing things in sharp focus which I don’t have and which makes our combination a good one.”

By his own admission, Kazan was then the most powerful director in America. He had successfully mounted the mid-century’s three most important Broadway plays—Thornton Wilder’s

The Skin of Our Teeth

, Williams’s

A

Streetcar Named Desire

, and Miller’s

Death of a Salesman

; his second film,

Gentleman’s Agreement

, had earned him an Academy Award. “Kazan, Kazan / The miracle man / Call him in / As soon as you can” went a bit of Broadway doggerel about his extraordinary prowess.

The Skin of Our Teeth

, Williams’s

A

Streetcar Named Desire

, and Miller’s

Death of a Salesman

; his second film,

Gentleman’s Agreement

, had earned him an Academy Award. “Kazan, Kazan / The miracle man / Call him in / As soon as you can” went a bit of Broadway doggerel about his extraordinary prowess.

Gadg, Kazan’s benign nickname, invoked his expertise as a handyman, which extended to tinkering with the construction of plots. He had a forensic sense of dramatic structure and how to fix or to finesse those parts of a story that weren’t working. In the case of

The Rose Tattoo

, he saw exactly Williams’s intention; he also saw his failures. “I do not think the material is organized properly,” he wrote. “It is, at any rate, not ready to produce, or to show.”

The Rose Tattoo

, he saw exactly Williams’s intention; he also saw his failures. “I do not think the material is organized properly,” he wrote. “It is, at any rate, not ready to produce, or to show.”

To trap the ineffable, Williams cast a wide, sprawling net. With un-collated pages scattered around him on the floor, from the outside, Williams’s way of working

looked

a mess; his early drafts

were

a mess. “Sometimes I can make a virtue of my disorganization by keeping closer to the cloudy outlines of life which somehow gets lost when everything is too precisely stated,” he told Kazan, adding, “Thesis and antithesis must have a synthesis in a work of art but I don’t think all of the synthesis must occur on the stage, perhaps about 40% of it can be left to occur in the minds of the audience. MYSTERY MUST BE KEPT! But I must not confuse it with sloppy writing which is probably what I have done a good deal of in Rose Tattoo.”

looked

a mess; his early drafts

were

a mess. “Sometimes I can make a virtue of my disorganization by keeping closer to the cloudy outlines of life which somehow gets lost when everything is too precisely stated,” he told Kazan, adding, “Thesis and antithesis must have a synthesis in a work of art but I don’t think all of the synthesis must occur on the stage, perhaps about 40% of it can be left to occur in the minds of the audience. MYSTERY MUST BE KEPT! But I must not confuse it with sloppy writing which is probably what I have done a good deal of in Rose Tattoo.”

Clotted with exasperating Sicilian speech, opaque symbolism, and a main character, Rosario—the womanizing but idealized husband—who didn’t do enough to make Pepina’s dramatic trajectory either properly comic or compelling, the kitchen-sink version was more morass than mystery. Pepina sounded hectoring, “like a radio turned up too loud,” Molly Day Thacher told Williams. Using the outlines of Williams’s cumbersome tale, Kazan sketched a new theatrical picture, providing Williams with a way to reconstruct the play that Williams would carry out almost to the letter:

I think if you start much later in the story and present a woman who is (as they used to say in the twenties) a frozen asset . . . with every hint in the world of the volcanic energy boiling towards freedom within her—why then you will have real suspense to see it break forth. I’d cut out Rosario. He is much more forceful as a memory, as a legend, something she speaks of, and in name of whom she rejects all other men, not only for herself but for her daughter. . . . This way Pepina will have the meaning of a broader idea. All women have within them a volcanic force, and we (civilization) have done everything possible to seal it off, and tame it. . . . In other words I would concentrate, if I were you, on these two very “moral” people: a woman who is apparently just a neighborhood seamstress and a man who is devoting his life to the traditional Italian (and Greek) virtue of supporting his helpless relatives. . . . And this woman, with her urn and the cachet of dynamite below her belt, and how that dynamite is exploded, darn near against her will. . . . And start much later: possibly with the graduation, and an introduction of Pepina as a very proper Seamstress that all the neighboring women . . . look up to. Then you have somewhere to go. . . . There is and should be something COMIC (in the biggest sense of that word: optimistic and healthy and uncontrollable) about the setting, the characters, the appertinences (I don’t know how to spell that word) and the effects.

Other books

Twenty-Five Percent (Book 2): Downfall by Wheatley, Nerys

Adam's Promise by Julianne MacLean

Out of the Blues by Mercy Celeste

Battlecry: Sten: Omnibus One (Sten Omnibus) by Allan Cole, Chris Bunch

Eternal Temptations (The Tempted Series Book 6) by Janine Infante Bosco

El cero y el infinito by Arthur Koestler

The Woman in the Fifth by Douglas Kennedy

Being Zen: Bringing Meditation to Life by Bayda, Ezra

Calvin’s Cowboy by Drew Hunt