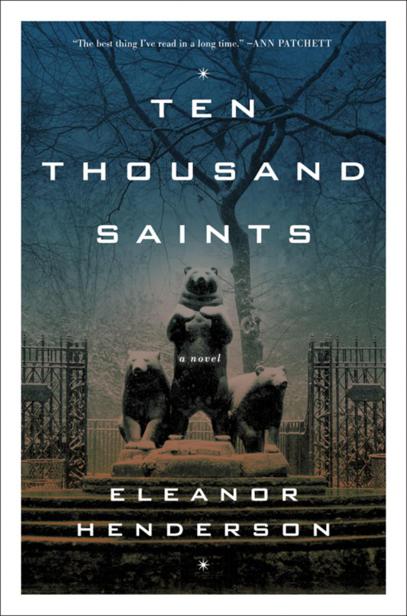

Ten Thousand Saints

Ten Thousand Saints

Eleanor Henderson

For Aaron

Behold, the Lord cometh with ten thousands of his saints,

To execute judgment upon all.

—THE BOOK OF JUDE

Contents

Sad Song

I

s it

dreamed

?” Jude asked Teddy. “Or

dreamt

?”

Beneath the stadium seats of the football field, on the last morning of 1987 and the last morning of Teddy’s life, the two boys lay side by side, a pair of snow angels bundled in thrift-store parkas. If you were to spy them from above, between the slats of the bleachers—or smoking behind the school gym, or sliding their skateboards down the stone wall by the lake—you might confuse one for the other. But Teddy was the dark-haired one, Jude the redhead. Teddy wore opalescent, fat-tongued Air Jordans, both toes bandaged with duct tape, and dangling from a cord around his neck, a New York City subway token, like a golden quarter. Jude was the one in Converse high-tops, the stars Magic Markered into pentagrams, and he wore his red hair in a devil lock—short in the back and long in the front, in a fin that sliced between his eyes to his chin. Unless you’d heard of the Misfits, not the Marilyn Monroe movie but the horror-rock/glam-punk band, and if you were living in Lintonburg, Vermont, in 1987, you probably hadn’t, you’d never seen anything like it.

“Either,” said Teddy.

They were celebrating Jude’s sixteenth birthday with the dregs of last night’s bowl. Jude leaned over and tapped the crushed soda can against Teddy’s elbow, and Teddy sat up to take his turn. His eyes were glassy, and a maple leaf, brittle and threadbare from its months spent under the snow, clung to his hair. Since Jude had known him Teddy had worn an immense pair of bronze frames with lenses as thick as windowpanes and, for good measure, a second bar across the top. But last week Teddy had spent all his savings on a pair of contact lenses, and now Jude thought he looked mole-eyed and barefaced, exposed, as Jude’s father had the time he’d made the mistake of shaving his beard.

With one hand Teddy balanced the bud on the indentation of the can, over the perforations Jude had made with a paper clip, lit it with the other, and like a player of some barnyard instrument, he put his lips to the mouth of the can and inhaled. Across his face, across the shadowed expanse of snow-stubbled grass, bars of sunlight brightened and then paled. “It’s done,” he announced and tossed the can aside.

Bodies had begun to fill the grandstand above, galoshes and duck boots filing cautiously down the rows, families of anoraks eclipsing the meager sun. Jude could hear the patter of their voices, the faraway din of a sound system testing, testing, the players cleating through the grass, praying away the snow. Standing on his wobbly legs, Jude examined their cave. They were fenced in on all sides—the seats overhead, the football field in front, a concrete wall behind them. Above the wall, however, was a person-size perimeter of open space, through which Teddy and Jude had climbed not long before, first launching their skateboards in ahead of them, then scaling the scaffolding on the outside, then tumbling over the wall, catlike, ten feet into the dirt. They’d done it twenty times before, but never while people were in the stadium—they’d managed to abstain from their town’s tepid faith in its Division III college football team; they abstained from all things football, and all things college. They hadn’t expected there to be a game on New Year’s Eve.

Now Jude paced under the seats and stopped five or six rows from the front. Above him, hanging from the edge of one of the seats, was a pair of blue-jeaned legs. A girl. Jude could see the dirty heels of her tennis shoes, but not much else. He reached up, the frozen fingers through his fingerless gloves inches away from her foot, but instead of enclosing them around the delicate bones of her ankle, he lifted the yellow umbrella at her feet. He slid it without a sound across the concrete and down into his arms.

“What are you doing?” whispered Teddy, suddenly at Jude’s elbow. “Why are we stealing an umbrella?”

Jude sprung it open and looked it over. “It’s not the umbrella we’re stealing,” he whispered back, closing it. Walking into the shadows a few rows back, he held it over his head, curved handle up, like a hook. In the bleachers above, there were purses between feet, saving seats, unguarded, alone, and inside, wallets fat with cash. Teddy and Jude had no money and no pot and, since this morning, nothing to smoke it out of but an empty can of Orange Slice.

Last night they’d shared a jug of Carlo Rossi and the pot they’d found in the glove box of Teddy’s mom’s car, while they listened to Metallica’s first album,

Kill ’Em All,

which skipped, and to Teddy’s mom, Queen Bea, who had her own stash of booze, getting sick in the bathroom, retch, flush, retch, flush. Around midnight, they’d taken what was left of the pot and skated to Jude’s to get some sleep, but in their daze had left Jude’s bong behind. When they returned to Teddy’s in the morning (this was the rhythm of their days, three rights and a left to Teddy’s, a right and three lefts to Jude’s), the bong—the color-changing Pyrex bong Jude’s mother had given Jude that morning as an early birthday gift—was gone. So were Queen Bea’s clothes, her car, her toothbrush, her sheets. Jude and Teddy wandered the house, flipping switches. The lights didn’t work; nothing hummed or blinked. The house was frozen with an unnatural stillness. Jude, shivering, found a candle and lit it. When Teddy opened the liquor cabinet, it was also empty—this was the final, irrefutable clue—except for a bottle of Liquid-Plumr and a film of dust, in which Teddy wrote with a finger,

fuck

.

Beatrice McNicholas had run away a few times before. She’d go out for a six-pack and come home a week later, with a new haircut and old promises. (She was no nester or nurturer; she was Queen Bea for her royal size.) But she’d never taken her liquor with her, or anything of Teddy and Jude’s.

The boys had stolen enough from her over the years to call it even. Five-dollar bills, maybe tens, that Queen Bea would be too drunk to miss in the morning, liquor, cigarettes. She was the kind of unsystematic drunk whose hiding places changed routinely but remained routinely unimaginative—ten minutes of hunting through closets and drawers (she cleaned other people’s houses, but her own was a sty) could almost always turn up something. Pot was more difficult to find at Jude’s house—his mom’s hippie habits were somewhat reformed, and though she condoned Jude’s experimentation (an appreciation for a good bong was just about all Harriet and Jude had in common), occasional flashes of parental guilt drove her to hide her contraband in snug and impenetrable places that recalled Russian nesting dolls. In Harriet’s studio, Jude had once found a Ziploc of pot inside a bag of Ricola cough drops inside a jumbo box of tampons inside a toolbox. While Queen Bea seemed only mildly aware that teenagers lived in her midst, sweeping them off her porch like stray cats, Harriet had a sharp eye, a peripheral third lens in her bifocals that was always ready to probe the threat of fast-fingered boys. So Jude and Teddy stole what was around: a roll of quarters from her dresser, the box of chocolates Jude’s sister, Prudence, had given her for Mother’s Day. They took more pleasure in what they stole out in the world: magazines and beer from Shop Smart (Shop Fart), video game cartridges from Sears (Queers), and cassettes from the Record Room, where Kram O’Connor and Clarence Delph worked. And half the items in Jude’s possession—clothes, records, homework—were stolen, without discretion, from Teddy.

But this bold-faced thievery beneath the bleachers embarrassed Teddy. It was so obvious, so doomed to failure. Sometimes Teddy thought that was the prize Jude wanted—not the money or the beer or the cigarettes but the confrontation, the pleasure of testing the limits. Jude was standing on tiptoe, umbrella still raised like a torch, eyeing the spilled contents of a lady’s bag. His tongue, molluscan and veined with blue, was wedged in concentration in the cleft under his nose.

“Hey,” said someone.

Teddy tried to stand very still.

A pair of eyes, upside-down, was framed between the seats above them. It took Teddy a few seconds to grasp their orientation—the girl was leaning over, her head draped over the ledge. “What are you doing?” she said.

Jude smiled up at her. “You dropped your umbrella.”