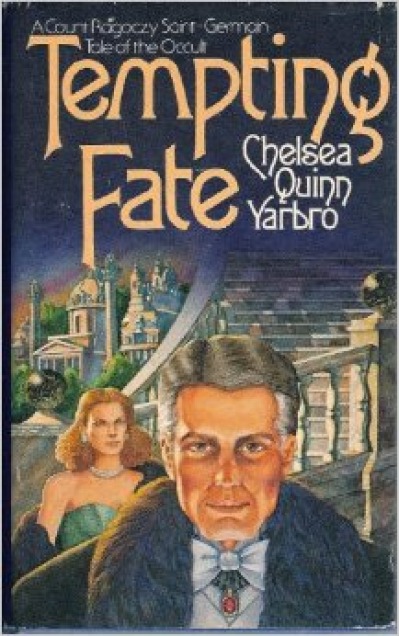

Tempting Fate

Authors: Chelsea Quinn Yarbro

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at:

us.macmillanusa.com/piracy

.

Contents

Part I:

Laisha Vlassevna

Part II:

Gudrun Maria Altbrunnen Ostneige

Part III:

Graf Franchot Ragoczy von Schloss Saint-Germain

Part IV:

Madelaine Roxanne Bertrande de Montalia

For the distinguished French filmmaker

François Truffaut

with sincere appreciation

for his cinematic alchemy

As with the other books in this series, every reasonable effort has been made to recreate the time of the action as it was. The early part of this century is still within living memory; journalistic, personal, photographic, cinematic, academic, and diplomatic documentation is available for most of the action and locales of this novel.

Time and history have not yet judged the latter half of the nineteenth century, let alone the twentieth, and opinions are varied and emotionally charged. Memoirs of this period have the insight that comes in retrospect rather than in the event, and for that reason I have approached them with caution, drawing from many sources rather than a few.

Of course there are errors, most of them inadvertent, a small number of them demanded by the course of the plot, for this is, after all, a work of fiction, and the story it tells, although occurring in recognizable places and concerned with real events, is the product of the writer’s imagination and should not be construed as representing or intending to represent any actual persons living or dead.

The writer wishes to thank the following persons for their generous help and assistance in the preparation of this book:

Ron Bounds

Sarah Chambers

Sharon McDaniel

David Nee

Edward Nicholls

Dr. and Mrs. Karl Schalfrant

Dan Nobuhiko Smiley

Natalie Wendruff

Errors in language and history are those of the writer, not of these expert advisers, whose memories and skills have been invaluable.

PART I

Laisha Vlassevna

Text of a letter from the American journalist James Emmerson Tree, to his cousin Audrey in Denver.

Portsmouth

September 21, 1917

Dear Audrey:

There were two more delays in London, which didn’t surprise me. You know what it’s been like so far, trying to get to Europe. Those reporters with the Associated Press have been having a little better luck, but those of us simply on assignment are at the bottom of the heap. Every time the question of passage comes up, it seems that the last men they have room for are reporters like me. I was talking to a man from Chicago, over here for the

Sun

, a couple of days ago, who said he’d been waiting for almost a month to get a space on a boat. He told me that he was getting so discouraged that he was thinking of renting a dinghy and getting himself across. However, as you see from the heading, I’ve made a little progress, and if all goes well, we’ll leave the day after tomorrow on a boat bound for Brest. Originally they were going to take us to Le Havre, but they think Brest is safer, because it’s about as far away as they can get us from the fighting and still land us in France. There’ll be five journalists and a couple of dozen nurses on the boat, so if I’m seasick again, it probably won’t matter.

Someday, when this war is finally over, you’ve got to get Uncle Ned to bring you over here to England. I knew it would be a revelation, but I never realized how much is crammed into this little place. It isn’t just in London that you keep tripping over history, you can find it everywhere. If Crandell will let me, I’m going to do some pieces on England and Europe that he can run when the war winds down, not just to say what’s happened since the Germans busted loose, but everything that went on before. If he isn’t interested, I know I can sell articles to magazines. Maybe

Century Magazine

or

Atlantic Monthly

would be interested if Crandell says no.

There’s a lot of rumors floating around London right now, and sitting in the pubs, you can hear most of them. I haven’t sent any back to Crandell, of course, because most of it’s just the usual run of wartime boasts and worries. Here in Portsmouth it isn’t as extreme, but London is alive with gossip. Everyone tells everyone else that they shouldn’t pass on rumors,

but

… and then they come out with the latest story. They can get pretty wild, sometimes. Since I’m from the other side of the Atlantic, and America’s just gotten into the war, many of the men I meet seem to think it’s okay to mention things to me. I told one man that I work for a newspaper and it might be wiser to keep his information to himself, since he couldn’t know what use I’d make of it. He smiled and said, “But it’s an

American

paper, isn’t it?” and then came up with a real whopper about machines that will blow all the poison gas back at the Huns. I let him rattle on about it for a while, and then I went back to Grantley’s place in Bloomsbury, which is where I’ve been staying since my hotel got taken over by a bunch of visiting European generals or adjutants, or whatever they are. My mail’s taking a little longer to get to me because of the move, so I haven’t had any letter from you since the one you sent August 2, which arrived yesterday.

In that letter, you said you were thinking about stopping your French lessons. Don’t you do it! You know how I used to grouse about learning it, and how it was silly and there was no point to it, and Madame Courante was a real witch, and all the rest of it. Well, let me tell you, Audrey, the last two months, I’ve been more grateful than I can say to that impossible old bat. It isn’t just that I can speak French that makes so many of the Europeans take a shine to me in spite of the fact that I’m an uncouth and uncultured American, but that I can speak it

right

. Aunt Myra’s doing you a favor, making you take those classes. I know it’s hard work and most of the kids in school think it’s a crazy thing to do, but take it from your Cousin James, you’ll be way ahead of the game if you stick with it.

I found out the other night that they’ve outlawed absinthe in France, so I won’t be able to tell you how it tastes, after all.

It’s a real pity about the censors in New York suppressing the Dreiser book; I finally got a copy of it, and it’s damned good. Fellow from Boston, of all places, brought it with him, and he’s staying at Grantley’s too, for the same reason I am. And if you ever tell Aunt Myra or Uncle Ned that I said “damned” to you, you better be wearing three pair of bloomers next time I see you.

It’s about time Uncle Ned got rid of that old Model A. I know it’s been a great automobile, but the last time I rode in it, it sounded like a goat digesting a load of tin cans. You need something that’s going to hold up through the winter. It may also surprise you to know that I think you ought to learn to drive. Aunt Myra doesn’t want to, and with Paul going into the army, there ought to be someone there other than Uncle Ned who can drive. Aunt Myra may want to shoot me for saying that, but I’d hate to think of you people being stranded out there, twelve miles from town. Even with the telephone in, it would be a help to have a second driver around.

Sorry, but I haven’t been able to find out anything about Tom McMillian, except what we already know, that he’s somewhere in France. From what I hear, Americans aren’t doing much fighting yet, so the chances are he’s safe. I’ll ask around some more when I get there, but don’t get your hopes up. It’s a huge war, and if what we’ve been told is accurate, it’s being botched by the people who shouldn’t make those kinds of mistakes. I know we’re not supposed to talk that way, or think that way, but I went to a hospital near here (and this is not to be repeated, young lady; this part is just between us, because it has to be) and I saw some of the men who’ve been at the Front, and I’ve learned what happened to them—those who could still talk sense told me about it—and that’s one of the reasons I really want to get over there. I know about soldiers’ bitterness, from what old Colonel Hurst said about Andersonville that time. Fifty years had gone by, almost, and he still couldn’t talk about the place without blaspheming. So I’m not sure that these are the men I should be listening to. That’s not to say I think we should forget them: everyone ought to know what it’s cost to hold the Huns back, not only in dead, but those who have had their lives taken away from them without the release of death.

Once I get to France, it’s going to be harder to send you letters. Most of my writing is going to have to be for the

Post-Dispatch

, and not for the family. If I make good over here, then it could mean I’ll have the career I want. They sent me over because I’m pretty expendable. If I get hurt, they can still pick up stories from American Associated Press. I haven’t kidded myself about that. But I’m going to make myself indispensable to them. So if you don’t hear from me for a while, don’t worry. I’ll do my best to write to you once a month, and trust that some of the letters get through. If anything bad happens, you’ll know about it. Remember that when my mother and Aunt Myra start thinking I’ve been shot.

You remember that reporter from Seattle I told you about? He got passage to Sweden and had arrangements made to get into Russia. He actually went through with it. Europe may be at war, but Russia’s exploding. He told us a little about what he’d found out from his contacts, and I tell you, that’s one place I’m staying out of until the dust really and truly settles. Don’t you fear for me unless you find out I’m being sent to Moscow.

Tell Aunt Myra and Uncle Ned I think about them often and fondly, and remember that I’m on your side, Audrey. This will have to be Happy Thanksgiving, too, I think, because I doubt you’ll hear from me again before Christmas. If you’re still saying prayers, say a few for me when you think of it, and for those poor soldiers in the trenches.

Until I write again, be good to each other.

Your loving cousin,

James

P.S. You might tell Madame Courante that I’m not as hopeless as she thought. I had a talk with a Captain in the French Army and he complimented me on the way I speak. He said I have a fine accent. She did a good job. But don’t let her give you a bad time. If France is anything like England, I can see why she might find Denver a bit of a comedown.

1

Petrograd was burning. The wind from the city was filled with soot and cinders and the greasy odor of charring things. Dark, close clouds hung low in the sky, molten with the lurid reflection of the flames. At this distance it was impossible to know what buildings were being destroyed: perhaps the palaces along the Nevsky Prospekt, or the Fortress and Cathedral of Saints Peter and Paul on the far side of the Neva.

The Monastery of the Victory was not far from Konstantinovka, nearer to Krasnoye Selo than to Petrograd, situated a fair distance from the road on a wide, treeless stretch of ground where the Imperial Guard had held maneuvers. It was an ancient building, with thick walls and small, barred windows. This made it an ideal prison.

Some twenty Cossacks held the monastery, guarding twice that number of prisoners. It had been a heady pleasure at first, but more than a week had passed and the excitement was beginning to pall. Now, with the last chaos of October 24 fading, most of the men had turned to the mundane business of securing billets with the villagers of Konstantinovka, leaving only their three officers to tend the monastery and the men incarcerated there.