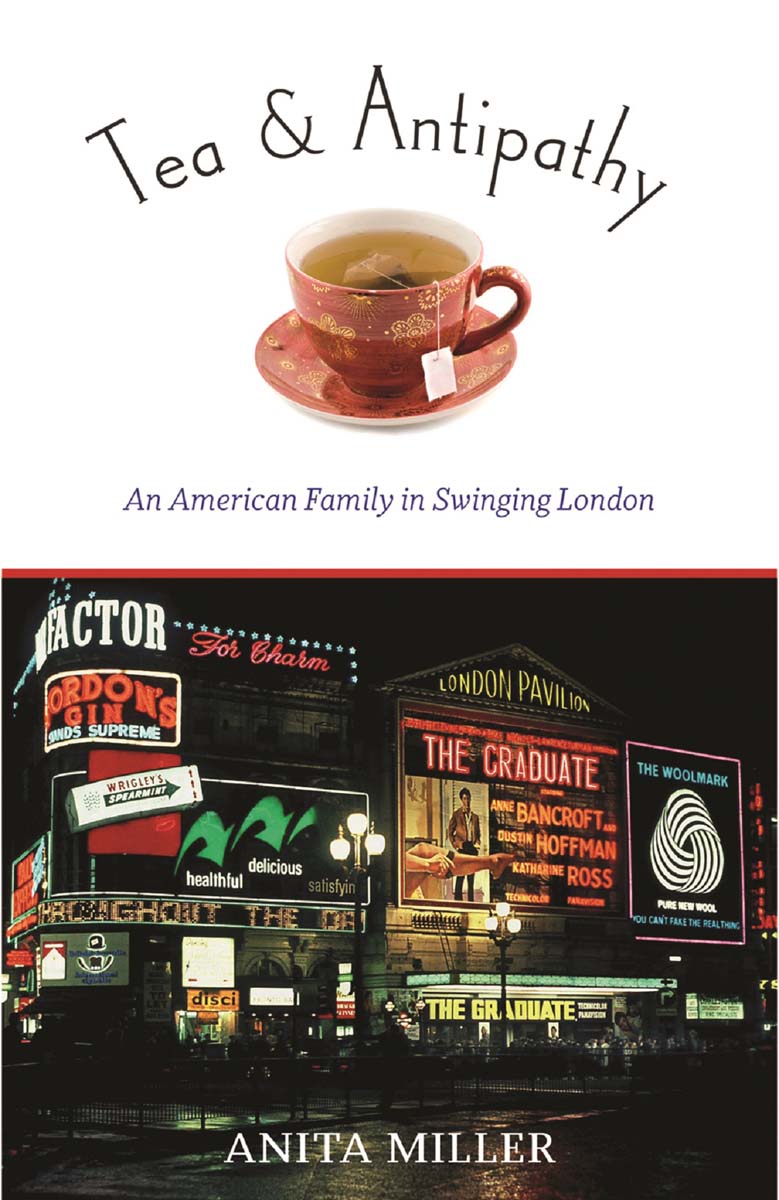

Tea & Antipathy

Authors: Anita Miller

For Mark, Bruce, and Eric. And Jordan.

Copyright © 2015 by Anita Miller

All rights reserved

Published by Academy Chicago Publishers

An imprint of Chicago Review Press, Incorporated

814 North Franklin Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

ISBN 978-0-89733-743-4

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Miller, Anita, 1926â

Tea & antipathy : an American family in swinging London / Anita Miller. âFirst edition.

pages cm

ISBN 978-0-89733-743-4 (cloth)

1. Miller, Anita, 1926- 2. Miller, Anita, 1926â-Family. 3. Miller, Jordan, 1926- 4. AmericansâEnglandâLondonâBiography. 5. Knightsbridge (London, England)âBiography. 6. London (England)âBiography. 7. Knightsbridge (London, England)âSocial life and customsâ20th century. 8. London (England)âSocial life and customsâ20th century. I. Title. II. Title: Tea and antipathy.

DA685.K58M45 2015

942.1085'6092âdc23

[B]

2014025481

Cover and interior design: Joan Sommers Design

Cover photo (bottom): Arbyreed

Printed in the United States of America

5 4 3 2 1

Anita Miller

founded Academy Chicago Publishers, Ltd, with her husband, Jordan Miller, in 1975. She earned her PhD from Northwestern University, and her doctoral dissertation was published by Garland Publishing. Dr. Miller has written, coauthored, or edited more than seventy-five books including

Uncollecting Cheever: The Family of John Cheever vs. Academy Chicago Publishers, Sharon: Israel's Warrior-Politician

, and

The Fair Women: The Story of the Woman's Building at the World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago 1893

. She has been awarded for distinction in editing and publishing by both London Women in Publishing and Chicago Women in Publishing.

PREFACE

Mark, fifteen; Bruce, ten; and Eric, seven.

Recently, five of us tried to eat lunch at two o'clock in the afternoon at a restaurant in a New York City hotel. All the tables were empty, but the hostess told us to wait. When I sought her out after ten minutes, she explained cheerfully that she was negotiating with the waitresses to see if one of them would be willing to take our order. They were still discussing it, and she did not see any point in seating us until a definite arrangement had been made.

This tiny incident transported me back more than four decades in time: I could have been standing in a London restaurant in 1965, thinking frostily that nothing like this could ever happen in the United States. As the years have dwindled away, I have thought often of that English summer. Now there is the general nostalgia over John Kennedy, over the Beatlesâ¦. It is perhaps a good time to tell the story of our summer vacation in Swinging London, when we began to lose our American innocence.

Departure

M

Y HUSBAND AND

I had always been Anglophiles. We had always believed that someday we would move to England and live a life of gentle Jamesian fulfillment. In 1963, as a first step toward the implementation of this dream, Jordan opened a London office of his Chicago press clipping service. For two years he commuted across the Atlantic, in an ever-increasing state of emotionalâand financialâdisrepair.

I remained at home, coping with our three sons and working on a master's degree in English literature. When I finally got the degree in the spring of 1965, Jordan was so overcome by guilt and the awareness that both he and his business venture had come to the end of their respective ropes that, as a special gift to his neglected family, he rented a house in Knightsbridge for us all for three months.

This announcement filled me with terror. “Three months,” I whispered. “What am I going to do with the children in London for three months?” Jordan, home on one of his sporadic visits, looked at me with the contempt of the foraging male for the cowardly cave-hugging female. “London is the most sophisticated city in the world,” he said. “If you can't find something amusing to do every day, I really feel sorry for you.”

I saw at once that he was right, and fell nervously into line. He was going to spend a fortune, or what was left of a fortune,

to make us happy, to atone for his long absence, and only an ungrateful shrew would whine at him about it. We still used words like “shrew” then, in the middle sixties.

Jordan came home to get us at the end of May, and at last we sat together on a British Overseas Airways plane, with Mark, fifteen; Bruce, ten; and Eric seven. As we grew nearer and nearer to the Old World, I could feel gross materialistic provincialism dropping away from us. The sun rose in the middle of the night; Eric woke every two hours, crying hysterically and attempting to stagger down the aisle to what I assume he thought was his bedroom. I had to keep seizing him and hauling him back. Finally the breakfast trays arrived and afterward, pale with excitement and lack of sleep, we saw the green land beneath us.

Sitting in the airport bus, carrying disreputable parcels with socks hanging out of them, I saw with pleasure the familiar black London taxis. I remembered our first visit to England two years before, without the children: smiling hotel porters, jovial waiters, helpful shop assistants. I thought of the Tate Gallery, Kensington Palace, the Burlington Arcade, Hatchard's. I thought of Jane Austen, antique shops, cashmere sweaters, Richard the Lion-Hearted, Penguin Books, country lanes and the stately homes of England. In an upsurge of emotion, I squeezed the arm of my eldest son, who shied like a frightened horse.

“Oh, Mark,” I cried, “it's going to be fun!”

Arrival

S

OMETIME WITHIN

the next two hours, we arrived at 16 Baldridge Place, which was to be our home for the summer. Baldridge Place was a quaint eighteenth-century street; all the houses were attached and painted white with gaily contrasting doors. Mrs. Stackpole, who owned Number 16, was unable to come at the moment; the friend she had sent in her place met us on the doorstep, gave us the key, and left without a word.

The distinct odor of mold that hit us in the face when we entered passed rapidly away.

“What's that awful smell?” Eric cried.

“The house is simply old, dear,” I responded. “Sometimes old houses smell odd at first. Oh, look at this lovely old sampler on the wall!”

“Eighteen-twenty,” Jordan said, reading from it. “Imagine that!”

We found ourselves in a red-carpeted entrance hall; the walls were covered with a red-and-white striped paper that continued up a graceful staircase.

“It's perfect,” I said. “A perfect English townhouse.”

“I knew you'd think so,” Jordan said gratefully. “And wait till you meet Mrs. Stackpole. She's charming.”

The little sitting room was rather bare. It did contain an interesting antique mahogany desk and small table, but there

was a bulky sofa and matching chair nakedly upholstered in a sort of early Pullman car boucle. “My goodness,” I said weakly. “That looks comfortable, doesn't it?”

Jordan, exhibiting some consternation, commented that Mrs. Stackpole appeared to have removed the slipcovers.

“English people are very fond of comfortable furniture,” I told the children.

“Boy, is that ugly,” Mark said.

The dining room contained only some dark stiff chairs, a little sideboard of a type often seen in Midwestern apartment hotels in the 1930s, a small fire screen with a woman's face embroidered on it, and a stained carpet. “The dining table's gone too,” Jordan said. “But I know she'll bring everything back. She's a lovely sort of person, really.”

“But look at those beautiful velvet curtains,” I said.

We all trailed down to the kitchen, in the basement.

“Why is the kitchen in the basement?” Eric asked.

“These houses were designed for servants,” I said. “A long time ago.” I went on to explain that Americans were spoiled, expecting everything at their fingertips, and it would be very good for us to climb a few stairs for a change.

Some efforts had apparently been made to update the kitchen: pipes were chopped into the walls and ceiling; the floor was covered with a lumpy, red linoleum, inexpertly patched together.

“Wow, look at this stove,” Bruce said. “It doesn't light.”

The stove, its iron legs gracefully bowed, stood in the old hearth, under a high narrow mantelpiece. Across the oven door was printed in Gothic script:

The New World

. “It must date from Columbus,” Mark said.

“We're all too materialistic at home,” Jordan said. “Anyone will tell you that.”

Bruce made a second attempt to light one of the burners. “None of these stoves are automatic,” Jordan remarked, with some impatience. From the warming rail, he picked up a sort of battery with a long curved neck. “You just press this button. You light English gas stoves with these clever little batteries.”

“Isn't that clever,” I said, after a minute.

“You're lucky to have a nice white sink and a refrigerator,” Jordan said to Mark.

“I am?” Mark said.

Next to the kitchen was what appeared to be a playroom with a blue linoleum floor, and down the hall was a laundry room; there was a new-looking washing machine in it. Jordan said that Mrs. Stackpole had told him that the washing machine was broken.

We went back upstairs to the ground floor, and then up the curving staircase to a landing where there were bookshelves in an alcove, and a bathroom with a green linoleum floor: decals of Bo-Peep and Little Mary Quite Contrary were pasted on the tub and the sink.

“Isn't that cute,” I said.