Tales of the Taoist Immortals (2 page)

Read Tales of the Taoist Immortals Online

Authors: Eva Wong

What are immortals? Were they mortals once, or have they been immortal since the beginning of time? The answer is a bit of both. In this book, you will find that some

immortals were spirits of stars or animals (Tung-fang Shuo and Chang Kuo Lao); some were mortals who had done good deeds and were rewarded with immortality (the sisters in the story of Ko Hsüan); some entered the immortal realm by ingesting a magical pill (the Yellow Emperor, Huai-nan Tzu, Ko Hung, and Wei Po-yang); and still others attained immortality by cultivating body and mind (Ssu-ma Ch’eng-chen, Chen Hsi-yi, and Chang Po-tuan).

Taoist immortals can be divided into four classes according to their level of cultivation. At the lowest level are the human immortals. Human immortals are not very different from ordinary mortals except that they live long and healthy lives. In this book, Fan Li, Hsi Shih, and Kiang Tzu-ya are examples of human immortals.

Next come the earth immortals. These immortals live for an unusually long period of time in the mortal realm, far beyond the life span of ordinary people. In this book, Tso Chi, Fei Chang-fang, and Chang Chung are examples of earth immortals.

Above the earth immortals are the spirit immortals, who live forever in the celestial lands. Some, like the Yellow Emperor, Wei Po-yang, and Wen Shih, take their bodies with them when they enter the immortal realm. Others, like Pai Yü-ch’an, Kuo P’u, and Chang Po-tuan, leave their bodies behind when they liberate their spirits.

At the highest level are the celestial immortals. These immortals have been deified and given the titles of celestial lord, emperor, or empress. Some, like Lao Tzu and Chuang Tzu, are de facto deities because they are considered manifestations of the cosmic energy of the Tao. Others, like Lü Tung-pin and Ho Hsien-ku, were “promoted” to deity status because of the meritorious works they had done in the mortal and immortal realms.

Taoist immortals are as diverse as any group of people. Some were healers (Fei Chang-fang and Chang Tao-ling); some were teachers (Lü Tung-pin, Kuei-ku Tzu, T’ai-hsüan Nü, and T’ao Hung-ching); and some were social activists and politicians (Fan Li, Hsi Shih, and Chang Liang). Some cultivated the Tao by living in seclusion (Ko Hung, Ts’ao Kuo-chiu, and Chang San-feng), and others lived in society but shunned the values of the establishment (Chuang Tzu and Chou Tien). There were scientists (Cheng Wei’s wife and Wei Po-yang); scholars (Ssu-ma Ch’eng-chen and Chang Po-tuan); poets (Han Hsiang and Lin Ling-su); military commanders (the Yellow Emperor, Chungli Ch’uan, and Kiang Tzu-ya); feng-shui masters (Kuo P’u and Ch’ing Wu); aristocrats (Huai-nan Tzu and Ts’ao Kuo-chiu); entertainers (Lan Ts’ai-ho and Tso Chi); householders (Ho Hsien-ku and T’ang Kuang-chen); and entrepreneurs (Fan Li and T’ai-yin Nü).

However, despite their diversity, the immortals all have these things in common: they were interested in the Tao at an early age; they shunned fame and fortune; and they lived simple and unencumbered lives. Some, following the example of Chuang Tzu, were never attracted to public life. Others, following the teachings of the

Tao-te-ching,

retired from public service after their work was done.

In the Taoist tradition, the stories of immortals are meant to teach as well as to entertain. For example, the stories of Fan Li and Hsi Shih, Chang Liang, Chou Tien, and Chang Chung warn us that power corrupts, and that even those with good intentions in the beginning (like Chu Yüan-chang and Liu Pang) can easily become murderous villains. In the story of the students of Kuei-ku Tzu, we learn the importance of knowing to retire at the appropriate time. The stories also promote virtues such as generosity (Ch’ing

Wu and Sun Chung), kindness (Ko Hsüan and the sisters), integrity and courage (Mah Ku), filial piety (Ho Hsien-ku and T’ang Kuang-chen), and dedication (Wen Shih).

Even the immortals themselves learned lessons in these tales. T’ao Hung-ching had to learn to value all sentient life (including worms and insects) before he could attain immortality; T’ieh-kuai Li was too vain and had to take on the appearance of an ugly cripple to learn humility before he could complete his training; and Lü Tung-pin had to be shocked by a nightmare before he would awaken from his illusions.

The immortals I have chosen to include in this book are the most well known and respected among the Chinese. Their names are household words, and their stories are told and retold throughout generations.

In telling these stories, I have tried to preserve the style of traditional Chinese storytelling. The immortals are listed in the category for which they are best known—sages, magicians, diviners, and alchemists. However, as you read the stories, you will notice that many immortals do not belong to one category exclusively. For example, Chen Hsi-yi, who is best known as a sage, was also a diviner, and T’ai-hsüan Nü, who is best known as a magician, was also an alchemist. The Eight Immortals, the most famous of the Taoist immortals, are included in a separate section and are listed in their order of seniority. As a group, the Eight Immortals represent the many facets of Taoist spirituality: teaching (Lü Tung-pin), alchemy (Chungli Ch’uan), female cultivation (Ho Hsien-ku), divination (Chang Kuo Lao), spirit travel (T’ieh-kuai Li), the hermit tradition (Ts’ao Kuo-chiu), an unencumbered lifestyle (Lan Ts’ai-ho), and love of the arts (Han Hsiang). No other immortals have inspired the cultural

arts of China or fired the imagination of the Chinese people as much as the Eight Immortals.

Taoist immortals have been role models for the Chinese for centuries and have represented everything that we value as a culture. Now, as more non-Chinese are beginning to embrace Taoism as a spiritual tradition, the immortals have taken on an even more significant role: they have gone beyond being cultural symbols of the Chinese to become universal examples of spiritual attainment.

I thank the writers of the Chinese operas, the storytellers on the radio and at Banyan Tree Park, and, most of all, my grandmother for passing on to me one of the greatest treasures of Taoism. I hope that you will enjoy these stories of the immortals as much as I have.

PART ONE

1

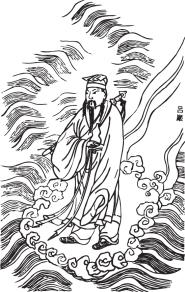

Lü Tung-pin

Lü Tung-pin’s original name was Lü Yen. It is said that when Lü Yen was born, the sound of flutes and pipes was heard and a white crane came to sit by his mother’s bed. The chamber was filled with fragrance, and multicolored clouds were seen hovering at the window.

Lü Yen’s grandfather was a supervisor of rites and rituals, and his father was a secretary in the police department. Like the sons of many government officials, he aspired to follow in the footsteps of his father and grandfather. He studied the Confucian classics, wrote poetry, and practiced the mar

tial arts. However, he was also interested in Taoism and admired the sages Chang Liang and Fan Li, who, after serving their country, had retired to cultivate the Tao.

When Lü Yen was twenty years old, he met a Taoist who told him, “You have the makings of an immortal and are destined to live in a thatched hut rather than a golden mansion. When you meet a man named Chungli Ch’uan, you should seize the opportunity.”

The years passed. Lü Yen had taken the civil service examinations twice and failed each time. On his way to the capital for one last try, he stopped at an inn for the night. By now, Lü Yen’s enthusiasm for a government career had diminished substantially. He sat at a table, ordered wine, and sighed as he drank. After a few mouthfuls of wine, he heard a voice behind him say, “No need to sigh and drink by yourself. Tell me what’s on your mind.”

Lü Yen turned and saw a man smiling at him. The stranger was dressed in a short tunic open down to his waist to reveal a tuft of hair on his chest. The legs of his pants were rolled up; he had straw sandals on his feet; his hair was tied into two knots on the sides of his head; and in his hand was a large fan.

Lü Yen was fascinated by the man. He walked over, sat down at the stranger’s table, and told him of his disappointment at not being able to serve his country. At the end of his story, Yen added, “I am ready to leave the world of fame and fortune and devote my life to cultivating the Tao.”

The strange man then said, “My name is Chungli Ch’uan. I am also called the Hermit of the Cloud Chamber. Would you like to follow me into the mountains and learn about the Tao?”

Lü Yen did not know what to do. On one hand, he wanted to abandon everything and follow Ch’uan into the

mountains. On the other hand, he was still attached to social conventions and responsibilities. When Ch’uan saw the conflict within Lü Yen, he said, “Come, let us have dinner. You can let me know later.”

After dinner, Lü Yen was still hesitant about following the strange man into the mountains. Ch’uan saw this and said, “I will not force you.” He then gave Yen a pillow as a parting gift.

That night, Lü Yen slept with his head on the pillow and dreamed that he had passed the civil service examinations and had become a high-ranking official. He was appointed chief minister in the emperor’s court; he married and had many children and grandchildren; and he was respected by all. Then the dream took an ugly turn. Lü Yen saw himself embroiled in court intrigues. Ministers jealous of Yen’s relationship with the emperor framed him for treason, and his entire family was arrested. First, all his male children and grandchildren were executed. Then, his family shrine was destroyed. Finally, he was exiled to the frontier, where he died, far from his surviving relatives.

Lü Yen woke up from his nightmare trembling and covered with sweat. Quickly, he ran out of his room to look for Ch’uan, who was sitting at a table having his morning tea. When he saw Yen, he said, “In one night, you have lived through twenty years of your life.”

“Then you knew about my dream?” asked Lü Yen.

The Taoist replied, “You achieved your goals in your dream, but you also lost everything. Gains and losses are illusions of the mortal realm. Only those who can see through illusions are capable of transcending them.”

“Take me with you into the mountains,” said Lü Yen. “From now on fame, riches, and social prestige are nothing to me.”

Chungli Ch’uan congratulated him, “You have awakened from your illusions—this is your first step to cultivating the Tao. However, before I can teach you the arts of longevity and immortality, you need to strengthen your foundations. Right now, your body is weak and your mind is cluttered. When you have built the proper foundations, I will come back to teach you.”

Lü Yen thanked Ch’uan and they parted. Yen walked out of the inn and told himself, “From now on, I am no longer Lü Yen the scholar. I will take the name Lü Tung-pin (guest of the cavern), for now I understand I am but a visitor in this realm learning how to return to my original home.”

Lü Tung-pin built a thatched hut and settled in the Chung-nan Mountains. He emptied his mind, strengthened his body, and lived the simple life of a hermit.

One day, Chungli Ch’uan appeared at the door of Tung-pin’s retreat and said, “I see that you have worked hard to cultivate your mind and body. Now you are ready to learn the Taoist arts. First, I’ll teach you how to turn stones into gold.”

Lü Tung-pin asked his teacher, “After the stones have been turned into gold, will they remain as gold forever?”

Ch’uan replied, “No. The gold nuggets will revert back to stones after three thousand years.”

Tung-pin then said, “I would rather not learn a technique that could potentially delude and harm people.”

Ch’uan sighed and admitted, “Your understanding of the Tao surpasses mine.”

After Lü Tung-pin had completed his training with Chungli Ch’uan, the elder immortal said, “I must return to the celestial realm. If you wish, you can journey with me.”

Tung-pin bowed to his teacher and said, “Our paths are different. You are meant to wander leisurely in the celestial

lands. As for me, I will not enter the highest realm of immortality until I have helped all sentient beings return to the Tao.”

Ch’uan bowed deeply to his former student and said, “Your deeds on behalf of the Tao will be far greater than mine.” With that, he walked into a bank of fog and disappeared. Lü Tung-pin descended from his mountain retreat and wandered around the countryside, teaching all those who wanted to learn about the Tao.