Sword Woman and Other Historical Adventures (26 page)

Read Sword Woman and Other Historical Adventures Online

Authors: Robert E. Howard

“So understanding was reached, and a leech was fetched for Sir Guiscard and such of the henchmen as had suffered scathe. Then followed much discussion, and Sir Guiscard had recognized you as one of those who banged on his door. Then Guillaume was discovered hiding, as from a guilty conscience, and he confessed all, putting the blame on you. Ah me, such a day as it has been!

“Poor Peter in the stocks since dawn, and all the villeins and serving-wenches and villagers gathered to clod him – they but just now left off, and a sorry sight he is, with nose a-bleeding, face skinned, an eye closed, and broken eggs in his hair and dripping over his features. Poor Peter!

“And as for Agnes, Marge and Guillaume, they have had whipping enough to content them all a lifetime. It would be hard to say which of them has the sorest posterior. But it is you, Giles, the masters wish. Sir Guiscard swears that only your life will anyways content him.”

“Hmmmm,” ruminated Giles. He rose unsteadily, brushed the straw from his garments, hitched up his belt and stuck his disreputable bonnet on his head at a cocky angle.

The friar watched him gloomily. “Peter stocked, Guillaume birched, Marge and Agnes whipped – what should be your punishment?”

“Methinks I’ll do penance by a long pilgrimage,” said Giles.

“You’ll never get through the gates,” predicted Ambrose.

“True,” sighed Giles. “A friar may pass at will, where an honest man is halted by suspicion and prejudice. As further penance, lend me your robe.”

“My robe?” exclaimed the friar. “You are a fool – ”

A heavy fist

clunked

against his fat jaw, and he collapsed with a whistling sigh.

A few minutes later a lout in the outer ward, taking aim with a rotten egg at the dilapidated figure in the stocks, checked his arm as a robed and hooded shape emerged from the stables and crossed the open space with slow steps. The shoulders drooped as from a weight of weariness, the head was bent forward; so much so, in fact, that the features were hidden by the hood.

“The lout doffed his shabby cap and made a clumsy leg.

“God go wi’ ’ee, good faither,” he said.

“

Pax vobiscum

, my son,” came the answer, low and muffled from the depths of the hood.

The lout shook his head sympathetically as the robed figure moved on, unhindered, in the direction of the postern gate.

“Poor Friar Ambrose,” quoth the lout. “He takes the sin o’ the world so much to heart; there ’ee go, fair bowed down by the wickedness o’ men.”

He sighed, and again took aim at the glum countenance that glowered above the stocks.

Through the blue glitter of the Mediterranean wallowed a merchant galley, clumsy, broad in the beam. Her square sail hung limp on her one thick mast. The oarsmen, sitting on the benches which flanked the waist deck on either side, tugged at the long oars, bending forward and heaving back in machine-like unison. Sweat stood out on their sun-burnt skin, their muscles rolled evenly. From the interior of the hull came a chatter of voices, the complaint of animals, a reek as of barnyards and stables. This scent was observable some distance to leeward. To the south the blue waters spread out like molten sapphire. To the north, the gleaming sweep was broken by an island that reared up white cliffs crowned with dark green. Dignity, cleanliness and serenity reigned over all, except where that smelly, ungainly tub lurched through the foaming water, by sound and scent advertising the presence of man.

Below the waist deck passengers, squatted among bundles, were cooking food over small braziers. Smoke mingled with a reek of sweat and garlic. Horses, penned in a narrow space, whinnied wretchedly. Sheep, pigs and chickens added their aroma to the smells.

Presently, amidst the babble below decks, a new sound floated up to the people above – members of the crew, and the wealthier passengers who shared the

patrono

’s cabin. The voice of the

patrono

came to them, strident with annoyance, answered by a loud rough voice with an alien accent.

The Venetian captain, prodding among the butts and bales of the cargo, had discovered a stowaway – a fat, sandy-haired man in worn leather, snoring bibulously among the barrels.

Ensued an impassioned oratory in lurid Italian, the burden of which at last focussed in a demand that the stranger pay for his passage.

“Pay?” echoed that individual, running thick fingers through unkempt locks. “What should I pay with, Thin-shanks? Where am I? What ship is this? Where are we going?”

“This is the

San Stefano

, bound for Cyprus from Palermo.”

“Oh, yes,” muttered the stowaway. “I remember. I came aboard at Palermo – lay down beside a wine cask between the bales – ”

The

patrono

hastily inspected the cask and shrieked with new passion.

“Dog! You’ve drunk it all!”

“How long have we been at sea?” demanded the intruder.

“Long enough to be out of sight of land,” snarled the other. “Pig, how can a man lie drunk so long – ”

“No wonder my belly’s empty,” muttered the other. “I’ve lain among the bales, and when I woke, I’d drink till I fell asleep again. Hmmm!”

“Money!” clamored the Italian. “Bezants for your fare!”

“Bezants!” snorted the other. “I haven’t a penny to my name.”

“Then overboard you go,” grimly promised the

patrono

. “There’s no room for beggars aboard the

San Stefano

.”

That struck a spark. The stranger gave vent to a war-like snort, and tugged at his sword.

“Throw me overboard into all that water? Not while Giles Hobson can wield blade. A free-born Englishman is as good as any velvet-breeched Italian. Call your bullies and watch me bleed them!”

From the deck came a loud call, strident with sudden fright. “Galleys off the starboard bow! Saracens!”

A howl burst from the

patrono

’s lips and his face went ashy. Abandoning the dispute at hand, he wheeled and rushed up on deck. Giles Hobson followed and gaped about him at the anxious brown faces of the rowers, the frightened countenances of the passengers – Latin priests, merchants and pilgrims. Following their gaze, he saw three long low galleys shooting across the blue expanse toward them. They were still some distance away, but the people on the

San Stefano

could hear the faint clash of cymbals, see the banners stream out from the mast heads. The oars dipped into the blue water, came up shining silver.

“Put her about and steer for the island!” yelled the

patrono

. “If we can reach it, we may hide and save our lives. The galley is lost – and all the cargo! Saints defend me!” He wept and wrung his hands, less from fear than from disappointed avarice.

The

San Stefano

wallowed cumbrously about and waddled hurriedly toward the white cliffs jutting in the sunlight. The slim galleys came up, shooting through the waves like water snakes. The space of dancing blue between the

San Stefano

and the cliffs narrowed, but more swiftly narrowed the space between the merchant and the raiders. Arrows began to arch through the air and patter on the deck. One struck and quivered near Giles Hobson’s boot, and he gave back as if from a serpent. The fat Englishman mopped perspiration from his brow. His mouth was dry, his head throbbed, his belly heaved. Suddenly he was violently sea-sick.

The oarsmen bent their backs, gasped, heaved mightily, seeming almost to jerk the awkward craft out of the water. Arrows, no longer arching, raked the deck. A man howled; another sank down without a word. An oarsman flinched from a shaft through his shoulder, and faltered in his stroke. Panic-stricken, the rowers began to lose rhythm. The

San Stefano

lost headway and rolled more wildly, and the passengers sent up a wail. From the raiders came yells of exultation. They separated in a fan-shaped formation meant to envelop the doomed galley.

On the merchant’s deck the priests were shriving and absolving.

“Holy Saints grant me – ” gasped a gaunt Pisan, kneeling on the boards – convulsively he clasped the feathered shaft that suddenly vibrated in his breast, then slumped sidewise and lay still.

An arrow thumped into the rail over which Giles Hobson hung, quivered near his elbow. He paid no heed. A hand was laid on his shoulder. Gagging, he turned his head, lifted a green face to look into the troubled eyes of a priest.

“My son, this may be the hour of death; confess your sins and I will shrive you.”

“The only one I can think of,” gasped Giles miserably, “is that I mauled a priest and stole his robe to flee England in.”

“Alas, my son,” the priest began, then cringed back with a low moan. He seemed to bow to Giles; his head inclining still further, he sank to the deck. From a dark welling spot on his side jutted a Saracen arrow.

Giles gaped about him; on either hand a long slim galley was sweeping in to lay the

San Stefano

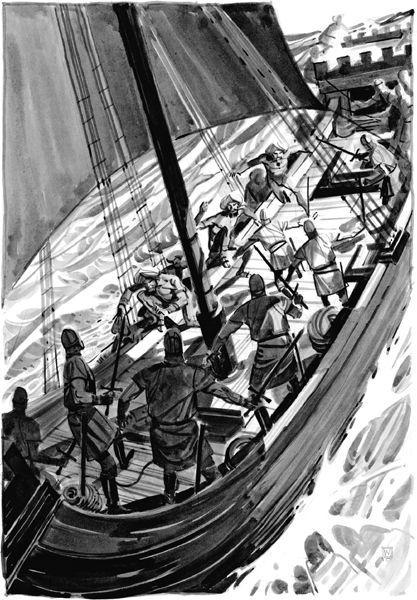

aboard. Even as he looked, the third galley, the one in the middle of the triangular formation, rammed the merchant ship with a deafening splintering of timber. The steel beak cut through the bulwarks, rending apart the stern cabin. The concussion rolled men off their feet. Others, caught and crushed in the collision, died howling awfully. The other raiders ground alongside, and their steel-shod prows sheared through the banks of oars, twisting the shafts out of the oarsmen’s hands, crushing the ribs of the wielders.

The grappling hooks bit into the bulwarks, and over the rail came dark naked men with scimitars in their hands, their eyes blazing. They were met by a dazed remnant who fought back desperately.

Giles Hobson fumbled out his sword, strode groggily forward. A dark shape flashed at him out of the melee. He got a dazed impression of glittering eyes, and a curved blade hissing down. He caught the stroke on his sword, staggering from the spark-showering impact. Braced on wide straddling legs, he drove his sword into the pirate’s belly. Blood and entrails gushed forth, and the dying corsair dragged his slayer to the deck with him in his throes.

Feet booted and bare stamped on Giles Hobson as he strove to rise. A curved dagger hooked at his kidneys, caught in his leather jerkin and ripped the garment from hem to collar. He rose, shaking the tatters from him. A dusky hand locked in his ragged shirt, a mace hovered over his head. With a frantic jerk, Giles pitched backward, to a sound of rending cloth, leaving the torn shirt in his captor’s hand. The mace met empty air as it descended, and the wielder went to his knees from the wasted blow. Giles fled along the blood-washed deck, twisting and ducking to avoid struggling knots of fighters.

A handful of defenders huddled in the door of the forecastle. The rest of the galley was in the hands of the triumphant Saracens. They swarmed over the deck, down into the waist. The animals squealed piteously as their throats were cut. Other screams marked the end of the women and children dragged from their hiding-places among the cargo.

In the door of the forecastle the blood-stained survivors parried and thrust with notched swords. The pirates hemmed them in, yelping mockingly, thrusting forward their pikes, drawing back, springing in to hack and slash.

Giles sprang for the rail, intending to dive and swim for the island. A quick step behind him warned him in time to wheel and duck a scimitar. It was wielded by a stout man of medium height, resplendent in silvered chain-mail and chased helmet, crested with egret plumes.

Sweat misted the fat Englishman’s sight; his wind was short; his belly heaved, his legs trembled. The Moslem cut at his head. Giles parried, struck back. His blade clanged against the chief’s mail. Something like a white-hot brand seared his temple, and he was blinded by a rush of blood. Dropping his sword, he pitched head-first against the Saracen, bearing him to the deck. The Moslem writhed and cursed, but Giles’ thick arms clamped desperately about him.

Suddenly a wild shout went up. There was a rush of feet across the deck. Men began to leap over the rail, to cast loose the boarding-irons. Giles’ captive yelled stridently, and men raced across the deck toward him. Giles released him, ran like a bulky cat along the bulwarks, and scrambled up over the roof of the shattered poop cabin. None heeded him. Men naked but for

tarboushes

hauled the mailed chieftain to his feet and rushed him across the deck while he raged and blasphemed, evidently wishing to continue the contest. The Saracens were leaping into their own galleys and pushing away. And Giles, crouching on the splintered cabin roof, saw the reason.

Around the western promontory of the island they had been trying to reach, came a squadron of great red

dromonds

, with battle-castles rearing at prow and stern. Helmets and spear-heads glittered in the sun. Trumpets blared, drums boomed. From each mast-head streamed a long banner bearing the emblem of the Cross.

From the survivors aboard the

San Stefano

rose a shout of joy. The galleys were racing southward. The nearest

dromond

swung ponderously alongside, and brown faces framed in steel looked over the rail.