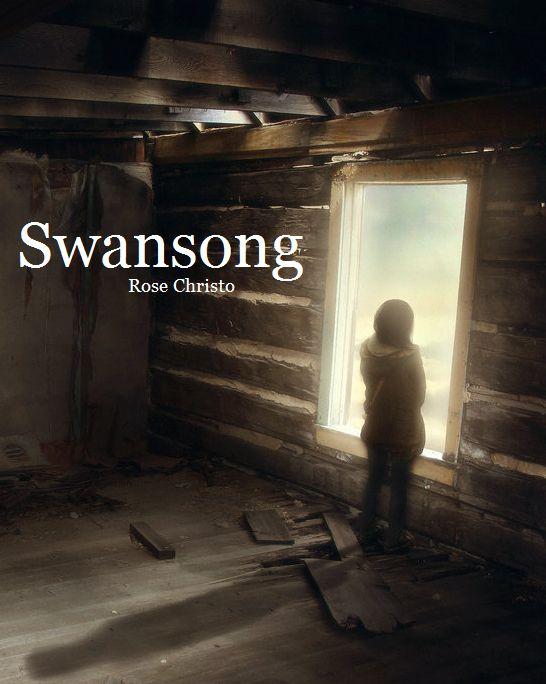

Swansong

Authors: Rose Christo

Swansong

Rose Christo

1

The Stranger

I bolt upright, gasping for air. The wires in my arms pull taut. Indiscriminate machines beep next to my bed.

My head bursts with pain.

“Honey,” says a woman in teal scrubs. She darts over to my bed.

“I—” I swivel my head, searching the room. Drab concrete walls. Blinds pulled shut over the window. It’s dark outside. A light behind the bed shines dully on my skull.

“—What happened?” I breathe.

The nurse slides a cuff around my arm and presses a button on the wall. Her eyes are downcast while she checks my vitals. My head is pounding, sharp. My throat is dry. I think—I think I’m going to throw up.

I grab the sick bag hanging off the bed rail. I throw up.

The nurse strokes the side of my head and I surface, gasping, blurry-eyed, the pain between my temples profound. She’s dark-haired, the nurse, with glazed, sad eyes. I feel her fingers raking softly over my skull. It dawns on me: There is no hair on my skull.

My cheek is throbbing and tight.

“Why am I in a hospital?” I rasp.

The nurse dabs the sick from my mouth with a sponge. She glances around, distracted. I can hear shoes scuffling outside my door, wheels rolling slickly beneath food carts, on-call buttons beeping.

A team of doctors bursts into my room like firefighters to a burning building. My skin is burning, hot pain concentrated at the base of my forehead. I lift my left hand, inspecting my fingers. They’re raw and red and scabbed, burnt flesh running up the length of my wrist.

“Oh—God—”

“Miss Rozas?” says one of the doctors. I can’t see him. Somebody shines a light in my eyes.

I reach for the sick bag with wet fingers. I throw up a second time.

“Miss Rozas,” the same doctor says. The light clicks off. The nurse sponges my mouth again, my tongue like chalk. My hands are shaking and slippery. My vision clears, then blurs, eyes filling with involuntary tears. “Do you understand what’s going on?”

“N-No.” I try to shake my head. Even that hurts. “No.”

“Can you tell me your name?”

But you just said it. “Wendy.”

“Do you know how old you are?”

“Sixteen.” Why am I here?

“Do you remember what happened? Do you remember why you’re here?”

“No—I—”

“Get a new emesis bag,” somebody says.

“Page the phlebotomist,” somebody else says.

“Enough,” the final voice says.

The final voice belongs to a woman. She’s dark-haired and dark-skinned, her face broad and elegant, her lips painted red.

“Leave us for a moment,” she tells her interns.

The doctors scamper out of the room. The nurse folds up the sick bag and carries it outside.

The doctor sits on the edge of my bed, long hair tumbling down her shoulder. She smiles softly. “Hey.”

“What happened?” My head hurts. My throat hurts. “I—was I in an accident?”

“What’s the last thing you remember?” Answer questions with more questions—isn’t that what they do on cop shows?

“I…cake,” I recall. I trail off. “We were going to get cake. Joss came over…”

“You don’t remember getting into the car?”

I stare at the doctor.

“Memory loss is common,” she says. I think she’s trying to console me. “You’ve suffered a traumatic brain injury.” It’s not working.

“Where’s Mom?” I ask. Mom was—she was baking a cake. She burned it. She’s not good with cake. Dad was the one who said we’d take a trip to the bakery. “Where’s Dad?” Where’s Joss? She flounced through the front door, ecstatic over her report card. She handed me a gift, a little wrapped box with a little yellow ribbon. I don’t think I opened it.

There’s silence in the hospital room. It stretches between the concrete walls; it bounces off the sealed door, echoing in my ringing ears.

“There’s been an accident,” the doctor says slowly.

“No.”

“You know what a corner crop is? When farmers put all their wares on the edge of a crossroads? And they pile them up high, and you can’t really see around them?”

“My dad’s a fisherman.”

“There was a car…”

“You’re wrong. I’m sorry. You have to be wrong.”

Another silence. A silence in which I can feel the air leaving my chest, can smell the bile hanging on the air.

The doctor touches the back of my hand. My hands are covered in sick. I want to apologize. The apology never reaches my lips.

“Your brother’s on his way,” she says. “He’ll tell you everything.”

* * * * *

I haven’t seen Judas in ten years. That’s how long of a sentence he got when the jury sent him away for manslaughter.

My brother is a stranger to me, a stranger sitting in the cushioned visitor’s seat beside my bed. I look at him and wonder whether Mom or Dad would recognize him. I don’t recognize him, although I should. His hair’s the same as mine—a cloud of thick gold. His eyes are the same as mine—stormy and gray. Even his freckles look like mine, spotty and dark on rosy skin. It’s the face you’d expect an angel to wear. That’s why it’s so jarring that it’s covered in healed knife wounds: the jagged scar on his right cheek, the silver scar running across his chin, the snag deformity at the corner of his mouth. He earned those scars in prison. He had to have, because I’ve never seen them before. He was nineteen when they took him away from us. He’s twenty-nine now.

He looks tired and beaten. He makes me think of closed doors.

“Jude,” I begin. “Mom and Dad—”

“Dead.”

My brother is a stranger. I knew him when I was six. He used to hang me from the coat rack by the back of my shirt.

“That can’t be,” I reply. My voice is quiet.

Judas shrugs. His shoulders are broad. His t-shirt’s worn out, a gray that used to be black.

“The car was totaled,” Judas says. “Mom, Dad. That little kid.”

My insides turn cold. “Little kid?”

“Some kid was in the car with you. Your age.”

He means Jocelyn, I realize. Joss. My best friend. Joss with her straight A’s and her witchy giggle and her rippling black hair.

Mom and Dad and Joss were in the car with me. Mom and Dad and Joss are dead.

“It doesn’t make sense…”

Judas shrugs a second time. He rubs his eye with a crumpled hand, his knuckles hairy. He drops his hand on his lap, his face sagging, his eyes cold.

My mom and my dad and my best friend. They’re all dead.

“That just—” My voice breaks. “That doesn’t make sense.”

I saw them only minutes ago. It doesn’t make sense.

“It’s life. Life never makes sense.”

Bile rises into my throat, acrid and foul. This time, I swallow it.

* * * * *

The sad-eyed nurse sends Judas from the room. She helps me sit up—dizzily, light-headed—and removes a chest tube I didn’t even know I was wearing. She takes out my catheter. If I were in a better frame of mind, I know I’d feel embarrassed.

“I want to see them,” I tell her. “Mom and Dad and Jocelyn. They can’t be dead.”

She puts her fingers on the underside of my wrist, the skin there red and raw. After some deliberation, she says, “You’re not going anywhere for a while.”

“I feel fine—”

“You’ve been in a coma for thirteen days.”

I slump, wide-eyed.

She smiles wryly. “I have to take you down to X-ray.”

“Where…where’s Judas?” I haven’t seen Judas in ten years.

“He’ll come back for you in the morning,” the nurse says.

“They’re not dead.”

“I know.”

She rolls a wheelchair over to my bed. Shakily, I swing my legs over the side of the mattress. I stand, the hospital slippers thick on my feet.

I sit back down, the room spinning around me.

“Take your time,” the nurse says.

This is a dream. This is a crazy, crazy dream.

* * * * *

Thirteen is the number of days I spent in a coma. Fifteen is the number of pictures the X-ray technician takes of my head. Four is the number of times I throw up in one evening. The night staff puts me on fluids, the IV wire feeding into the back of my hand. I can’t feel the needle, even when blood beads and dries around the entry point. I can’t feel anything except the constant pounding inside my skull. It’s audible, even:

Thud.

Thud.

Thud.

The rhythm pierces my temples and torments my ears. The room swims around me in shades of black and color; black and color.

A bearded man with a big belly walks into the room. He looks at me over the tops of his eyeglasses and smiles. “I know I promised you a pudding cup,” he says, “but your chart says you shouldn’t. Sorry.”

“What?” What is he— “Who are you?”

“Forgot me again?”

He points at a sticky note taped to the wall beside my head. In my handwriting, it reads:

Dave. Physical therapist. Santa belly, glasses.

My face goes cold; then numb.

“It’s fine,” Dave says. He pulls a chair over to my bed. “Don’t panic. This is very common with an injury like yours.”

“Will it go away?” Where’s Mom? Where’s Dad?

“It’ll get…better,” Dave says diplomatically. He scratches his beard.

“But it doesn’t go away?”

“Pieces of your skull perforated the temporal-parietal-occipital junction. The swelling’s gone down, but there’s not much we can do in the way of restorative surgery.”

My hands fly to the crown of my head. Immediately I feel it: a long scar snaking from crown to base. Several smaller scars skitter around its radius, some as thick as my fingers.

“This isn’t happening,” is all I can think to say. This doesn’t make sense. This doesn’t happen to teenagers picking up cakes from bakeries. This—what is this?

“I know this is a hassle,” Dave says. “But we need to get started on therapy right away. It’s important to preserve as many functions as possible.”

“They said—” No; none of this makes sense. “They said Mom and Dad…” I can’t say it. “And my best friend.” If they’re all—if they’re—then how am I still here? How am I still alive? It doesn’t make sense. A world they’re not a part of—that doesn’t make sense.

Dave looks so sad, for a moment all I see is a little boy. The moment passes.

“Let’s get started,” Dave says.

The exercises start off small. Dave pulls out a deck of cards and makes me play a round of War with him. I don’t know how I’m supposed to concentrate, my head racing and aching, my fingers shaking. He makes me identify money—the big coin’s the quarter; the tiny coin’s the dime—he makes me stack them different ways and count them, again and again. Once Dave’s satisfied, he has me pour a cup of water from a plastic pitcher. I spill the water all over the bed tray.

“Don’t worry about it,” Dave says. He stands, looking for paper towels.

“My hands.” I put the pitcher down. I lift my hands so I can look at them. They’re twitching like leaves on an autumn day. My left hand is burned red, bumpy and coarse with skin grafts. I don’t recognize it. I don’t recognize me.

“It’s very likely that that symptom will disappear with time.” Dave finds the paper towels. He dries the mess I’ve made.

“I paint,” I tell him. I go to Cavalieri School of Performing and Visual Arts. Mom and Dad were so happy when I got in. Two years ago. That’s how I met Joss.

Mom and Dad—Joss—there’s no way. There’s just no way.

“I’m sure you’ll be able to paint again,” Dave says.

That warm, encouraging tone—I want to trust it. But I can’t.

* * * * *

An orderly stops by with a late dinner for me. I crumble a piece of toast in gravy, but don’t eat it. I think I’d choke if I tried.

It’s quiet in this room. Peaceful, almost, but eerie in its tranquility. Alone with my thoughts, I finally have the time to think.

They say my family is dead. My best friend, too.

They say there was a car accident.

I don’t remember any of it.

Was Dad driving? Dad’s a lousy driver. It’s not his fault; he belongs on the ocean, not on the road. Was Mom driving? She’s more careful behind the wheel than Dad is. She’s a backseat driver, too. How could there have been an accident if Mom was in the car?

Joss was in the car.

Jocelyn’s parents. They must be so—

They’re not dead. Mom and Dad and Joss. They’re not dead.

I’m sitting here in a hospital, and it’s midnight, and tomorrow morning Mom and Dad will come running into my room, relieved that we’re all okay. Mom and Dad can’t be gone. I’ve known them for sixteen years. How can I just wake up one day and not know them anymore? That doesn’t make sense. Right?