SUNK

Authors: Fleur Hitchcock

For the longshoremen of the Isle of Wight,

both past and present, especially Dad.

- Title Page

- Dedication

- Prologue

- 1 What?

- 2 Cold Chips

- 3 Mum vs Tilly

- 4 Click

- 5 Smoothie Volcano

- 6 Die, Pasta, Die

- 7 Mr Bell’s Cardigan

- 8 Like a Zombie

- 9 But, Mum, you CAN’T

- 10 Pineapple Soup

- 11 A Gust of Wind

- 12 An Extra-large, Double Chocolate Golden Syrup Sponge Ninety-nine, Please

- 13 Potato Clock

- 14 Best Sunday EVER

- 15 No One Calls a Teacher by their First Name

- 16 Walking on Sunshine

- 17 It Takes Twenty-three Coins

- 18 Kind of Cute

- 19 Not Kind of Cute

- 20 Foggis Fogg was the First

- 21 Is That a Bad Thing?

- 22 If It’s All Under Control?

- 23 No Problem

- 24 Jacob vs Deckchairs

- 25 Scrambled Egg (1)

- 26 Good Old Jacob

- 27 Scrambled Egg (2)

- 28 VOTE!

- 29 Fogg, Frog and a Bucket

- 30 Baby Otter Loses his Hair

- 31 Empathy?

- Also By Fleur Hitchcock

- Copyright

I was shocked by just how angry the deckchair was.

One minute, we were getting on with a sunny Sunday on the beach. The next, Mr Bissell was racing over the sand, screaming. Apparently pursued by a deckchair.

It’s impossible, I know.

But I saw it.

‘Dad,’ I say on the way home from the beach, laden with buckets and rolly-up things that

keep on unrolling. ‘Did you notice anything odd?’

‘Odd, Tom? No,’ says Dad, swinging a spade onto his shoulder. ‘People can get into terrible pickles with deckchairs. So difficult to manage – I never know which bit goes where.’

‘Oh,’ I say.

But I can’t stop thinking about it.

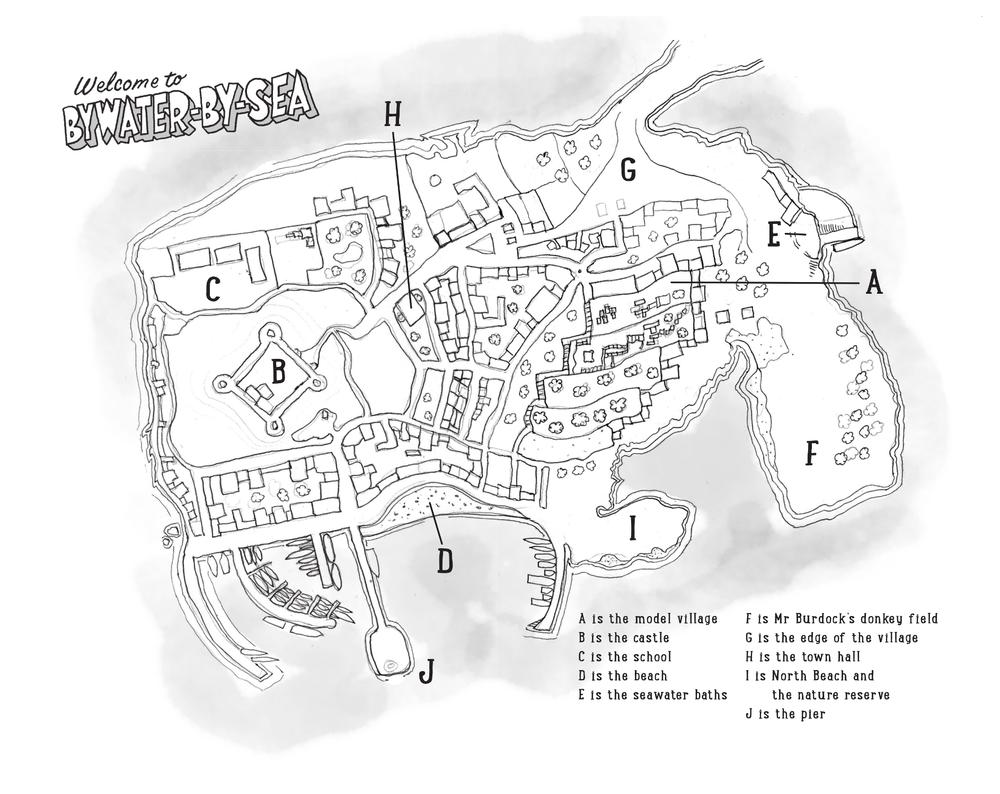

Yesterday was the last day of the Easter holidays, and today is the first day of the summer term, so a wet sea squall has blown in and is having a tantrum all over town. I pull my waterproof tight over my chest and thrust my hands deep into my pockets and wait for the school bus at the bus shelter by the model village.

A moment later, Tilly, my younger sister, arrives by my side, and we stand in mutual silence by the road, getting soaked.

‘Morning, chaps. Bracing, isn’t it?’

Dad?

‘What are you doing here?’ says Tilly.

‘Guess,’ says Dad, rubbing his hands together.

Tilly looks disgusted. ‘Dunno, I can’t imagine.’

Dad smiles smugly and says nothing else.

The bus arrives and we all three climb on. Dad sits at the front with the driver, Tilly joins her friend Milly, and I roll to the back to sit next to Eric.

Eric puts down his copy of

150 Alternative Ways to Spend the Summer Holidays

and looks up. ‘Morning, Tom. Why’s your dad on the bus?’

I shake my head. I feel about 9% good about the answer to that question.

Eric raises his eyebrows, which means that some pale hairs that are barely visible on his freckly face move closer to some slightly red

hairs boinging all over his forehead like broken springs. ‘Really?’ he says.

I look around. All the usual suspects are there, mostly staring at the lashing rain outside, but some are staring at Dad because no dad ever, ever, ever has, in the history of school buses, caught the school bus. Surely?

Why would my dad be the first?

‘Hey, Model Village,’ says Jacob from the back seat. ‘Daddy coming to school with you today? Is he coming to hold your hand?’

I try to ignore him. ‘Did you have a good holiday, Eric?’ I ask.

‘Yes,’ says Eric, looking at me strangely. ‘You know I did.’

‘Good,’ I say. I stare out of the window and I feel a blush start at the bottom of my back and spread up over my face until I’m sure that I’m completely beetroot.

Something appalling has occurred to me. A vision. Something that’s been part of our lives all holiday. In my mind’s eye I can see the kitchen table, with the

Bywater-by-Sea Gazette

open on page 17 and one advert ringed in red. I’ve even read it and I know that between the adverts for LOST –

ONE TORTOISE

and FOUND –

ONE TORTOISE

is one that says: JOB OFFERED. BYWATER-BY-SEA SCHOOL –

REQUIRED: TEACHING ASSISTANT.

I

MMEDIATE START.

‘OH! No!’ I mutter.

‘What is it?’ says Eric.

‘It’s Dad, he’s going to be working at school – every day, all the time.’

‘Oh dear,’ says Eric. ‘Oh dear, Tom. You have my deepest sympathies.’

It takes me until break to remember that I want to tell Eric about yesterday’s deckchair-on-the-beach episode. And when I finally find him feeding the Mongolian hawk-moth caterpillars in Mr Bell’s classroom, I have walked past Dad handing out juice in the playground three times.

‘Hi, Tom,’ Dad shouts with enthusiasm. ‘Great working here. Lovely to be with you all day.’

All of Year 1 turn and stare as I bolt across the playground.

‘How’s it going?’ asks Eric, tempting a particularly large and repulsive orange caterpillar with a nettle.

‘With Dad? Awful,’ I say. ‘But that’s not the point. The point is that something happened on the beach yesterday.’

‘Oh?’

‘It sounds really silly, but a deckchair attacked Mr Bissell.’

‘Attacked how?’ Eric puts down the first nettle and picks up a second. They look exactly the same.

I think back to what I saw. ‘It folded round him. It sort of pinched him inside.’

Eric drops the second nettle in the tank and turns to face me. ‘Fascinating. Just the one?’

‘Yes – only one.’

‘Did anyone else see?’

Once again I try to remember the scene

exactly as it happened. ‘Mum was reading the paper. Dad was building a sandcastle. Mr Bissell’s wife must have seen, although she might have been asleep. Oh and Mr Fogg –’

‘Albert Fogg – the longshoreman?’

‘Yes, him, the one with the beard. The man who hires out the deckchairs and eats crab sandwiches under an umbrella. He must have seen.’

Eric looks wise for a long time before saying, ‘Why’s your dad taken a job here? I thought he was going to be a magician?’

At lunch, I have to hide behind the bins in the rain.

‘Tom, Tom!’ Dad’s wandering around the playground looking for me. He’s wearing a checked pair of trousers, an apron and rubber gloves. ‘Tom, love, I thought we could

eat lunch together. We could share a bag of crisps.’

‘Hiding from Daddy?’ says Jacob, rolling round the corner and settling next to the bins. He pulls an enormous greasy package from his pocket.

‘What’s that?’ I ask.

‘Yesterday’s chips,’ he says. ‘Want one?’

I shake my head. ‘I thought they’d banned chips,’ I say.

‘They have,’ he says. ‘That’s why I’m round here hiding with a loser like you. No way am I eating salad – so I’ve brought my own packed lunch.’

He prises a long, soggy, flaccid chip from the pile and dangles it into his mouth. Not only is it cold but it has ketchup embedded between it and the greasy polystyrene box. Jacob’s lips close round it and he begins to chew. ‘So,’ he

says. ‘Where’s Snot Face? Thought you two were always together?’

Snot Face is what Jacob calls Eric. It’s unkind, but then Jacob is unkind.

‘I’m here,’ says Eric. ‘And do stop calling me “Snot Face”, please, Jacob.’

‘As you like, Snot Face,’ says Jacob, wiping his mouth with the back of his sleeve.

Eric ignores him. ‘So, Tom, what we need is a closer look at that deckchair.’

‘What deckchair?’ says Jacob.

‘The one that attacked Mr Bissell on the beach,’ says Eric.

‘Sounds exciting,’ says Jacob. ‘Did it kill him?’

‘No,’ I say.

‘And would it be better if it had?’ Eric asks Jacob.

‘Yes,’ says Jacob.

We both stare at him.

‘Was that the wrong thing to say?’ says Jacob, polishing off another chip.

‘Anyway.’ Eric turns back to me. ‘Do you think you can get a sample?’

But before I manage to answer, we’re interrupted by Dad. ‘Tom, darling – there you are. What on earth are you doing here in the rain? Now, boys, come and join me, and I can show you how the potato-peeling machine works. It’s absolutely thrilling.’

It almost kills me. The worst bit is when Dad takes the checked trousers off in the middle of the dining room. He has got shorts on underneath but how was I to know that?

At the end of the day, Dad gets on the school bus, whistling, and insists on chatting to everyone. The bus burbles around the town shedding passengers. Dad talks to them as they go.

‘Right, Dad,’ says Tilly when we finally get off the bus in a howling gale at the bottom

of the model village. ‘We are going to have some rules.’

‘Yes,’ I say, for once in total agreement with her.

‘Number one,’ she says, struggling to put up her pink umbrella. ‘You are not allowed on the school bus.’

‘Number two,’ I say. ‘We do not eat lunch with you.’

‘Number three,’ says Dad. ‘You two don’t tell me what to do, so put up with it. I’ve got a job at your school and if you want to eat then that’s the way it’s going to be.’

‘OHHHWWW! Dad!’ shouts Tilly. ‘That’s so unfair!’

‘It is, isn’t it?’ he says, swinging off through the model village whistling.

I stand staring at his back, my heart sinking and sinking. I feel 1% good about this.

‘We’ve got to stop him,’ says Tilly. ‘This can’t go on. I’ll die if he asks me one more question about trestle tables. We’ll have to have a word with Mum. What are you doing now?’

‘Um …’ I say. ‘Going to the beach?’

‘Don’t be ridiculous, Tom. In this?’ She waves her hand through the torrential rain.

So I follow her up to the house.

But Mum’s drawing red circles on the newspaper too.

‘Shall I train as a plumber?’ she asks.

‘Very small spaces, dear,’ says Grandma, taking a large carving knife to some raisin shortcake and loading it onto inadequately small plates. ‘You won’t like it.’

‘Or an electrician?’

We all stare at Mum. Last time she did anything electrical it was to stick a screwdriver

in the top of the washing machine and nearly blow up herself – and the house.

‘All right. What about welding? Could I do welding? Or I could be a yoga teacher or learn to make cheese. Or perhaps I should join the –’

‘Mum, can you just be quiet?’ says Tilly, grabbing a pencil off the table and using it to scratch her head.

Grandma frowns, but Mum turns to Tilly and beams.

‘Look,’ says Tilly, ‘it was bad enough when you and Dad were going to be magicians, but things are much, much worse now.’

‘Oh?’ says Mum.

‘Dad, at school. I’m serious, he is not coming into school again. Ever.’

‘Why?’ says Mum, reddening.

‘Because he’s awful – he behaves like …

like … like a puppy!’ shouts Tilly. ‘He cannot, I repeat, cannot, come to school again.’

Grandma scowls. Mum folds the paper and opens it again. She doesn’t actually look Tilly in the eye. ‘NO,’ she says. ‘He

will

be going to school tomorrow, and the next day. It’s his job.’

Tilly looks as if she’s going to explode. ‘WHAT!!!???’

‘And we’d be very grateful if you were actually able to be supportive.’

Tilly doesn’t say anything this time but she turns red, then white, then a little green before racing from the room, screaming.