Summer for the Gods: The Scopes Trial and America's Continuing Debate Over Science and Religion (21 page)

Authors: Edward J. Larson

BOOK: Summer for the Gods: The Scopes Trial and America's Continuing Debate Over Science and Religion

9.96Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Another Christian theology expert argued for the defense that science and religion could never conflict because they belonged to separate spheres of knowledge. “To science and not to the Bible must man look for the answers to the questions as to the process of man’s creation,” he offered to testify. “To the Bible and not science must men look for the answer to the causes of man’s intelligence, his moral and spiritual being.”

24

By presenting these two witnesses along with Mathews, the defense effectively demonstrated various ways that American Christians harmonized sincere religious faith with the findings of modern science.

24

By presenting these two witnesses along with Mathews, the defense effectively demonstrated various ways that American Christians harmonized sincere religious faith with the findings of modern science.

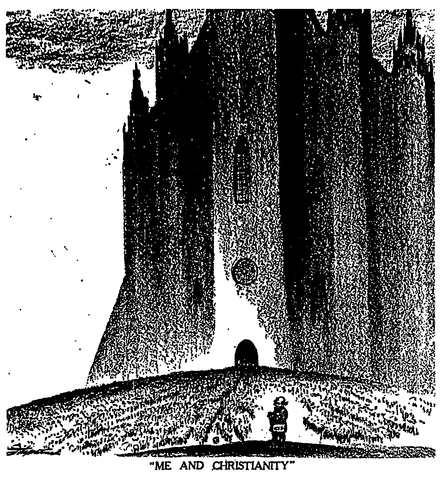

Editorial cartoon suggesting that many Christians did not agree with Bryan’s attackson the theory of evolution. (Copyright © 1925

New York World.

Used with permission of The E. W. Scripps Company)

New York World.

Used with permission of The E. W. Scripps Company)

The popular press seemed intent on pitting fundamentalists such as Bryan and Riley against modernists such as Mathews and Fosdick, or against agnostics such as Darrow, all of whom scorned the middle. Bryan, for example, publicly dismissed theistic evolution as “an anaesthetic that deadens the Christian’s pain while his religion is being removed,” while Mathews rejected attempts to retain Mosaic concepts of morality without Mosaic concepts of creation.

25

During the twenties, these two extremes gained adherents at the expense of the middle—and each claimed to represent the future of Christianity. Their clash spawned the antievolution movement and well deserved the attention it received during the Scopes trial. Christians caught in the middle sat on the sidelines.“The thing that we got from the trial of Scopes,” a Memphis

Commercial Appeal

editorial observed, was that most “sincere believers in religion” simply wanted to avoid the origins dispute altogether. “Some have their religion, but they are afraid if they go out and mix in the fray they will lose it. Some are afraid they will be put to confusion. Some are in the position of believing, but fear they can not prove their belief,” the editorialist noted, so they leave the field to extremists such as Darrow and Bryan.

26

25

During the twenties, these two extremes gained adherents at the expense of the middle—and each claimed to represent the future of Christianity. Their clash spawned the antievolution movement and well deserved the attention it received during the Scopes trial. Christians caught in the middle sat on the sidelines.“The thing that we got from the trial of Scopes,” a Memphis

Commercial Appeal

editorial observed, was that most “sincere believers in religion” simply wanted to avoid the origins dispute altogether. “Some have their religion, but they are afraid if they go out and mix in the fray they will lose it. Some are afraid they will be put to confusion. Some are in the position of believing, but fear they can not prove their belief,” the editorialist noted, so they leave the field to extremists such as Darrow and Bryan.

26

The middle did not remain entirely silent. President Hibbon of Princeton loudly complained about the trial, “I resent the attempt to force on me and you the choice between evolution and religion.” Some religious scientists used the opportunity to promote nonmaterialistic theories of evolution. Many were modernists, like Osborn, but others were orthodox, such as the Vanderbilt University science professor who wrote into the

Nashville Banner,

“As a scientist, I believe that the theory of Lamarck concerning the inheritance of acquired characteristics is probably in the process of being verified.”

27

That would resolve the controversy, the writer maintained. Such subtle arguments, however, attracted few headlines in newspapers bent on dramatizing the conflict between science and religion.

Nashville Banner,

“As a scientist, I believe that the theory of Lamarck concerning the inheritance of acquired characteristics is probably in the process of being verified.”

27

That would resolve the controversy, the writer maintained. Such subtle arguments, however, attracted few headlines in newspapers bent on dramatizing the conflict between science and religion.

Even James Vance, the leading proponent of moderation within Tennessee’s religious circles, added little to the public debate over the Scopes trial. Vance served as pastor of the nation’s largest southern Presbyterian church and once held the denomination’s top post. In 1925, readers of a leading religious journal voted him one of America’s top twenty-five pulpit ministers, along with fundamentalist Billy Sunday and modernist Harry Emerson Fosdick. When the antievolution movement first began in 1923, Vance and forty other prominent Americans, including Conklin, Osborn, 1923 Nobel laureate Robert Millikan, and Herbert Hoover, tried to calm the waters with a joint statement that assigned science and religion to separate spheres of human understanding. This widely publicized document described the two activities as “distinct” rather than “antagonistic domains of thought,” the former dealing with “the facts, laws and processes of nature” while the latter addressed “the consciences, ideals and the aspirations of mankind.” It offered no reasoned reconciliation of the apparent conflicts between them, however.

28

In 1925, Vance joined thirteen moderate or liberal Nashville ministers in petitioning the Tennessee Senate to defeat the “unwise” antievolution bill. After reading the petition on the Senate floor, however, even an opponent of the legislation had to concede “that there was no reason assigned in the written request” for defeating the bill.

29

28

In 1925, Vance joined thirteen moderate or liberal Nashville ministers in petitioning the Tennessee Senate to defeat the “unwise” antievolution bill. After reading the petition on the Senate floor, however, even an opponent of the legislation had to concede “that there was no reason assigned in the written request” for defeating the bill.

29

Vance had plenty of company straddling the fence over the Scopes case. Most national politicians followed the lead of President Calvin Coolidge in dismissing the case as a Tennessee matter. Tennessee politicians tended to mimic their governor, who defended the law and denounced the trial, but who clearly wished to avoid the entire issue and vowed to stay away from Dayton. Very few state legislators attended the trial, despite offers of reserved seating. Even the law’s author, J. W. Butler, only showed up after a newspaper syndicate offered to pay him for commentary on the proceedings. Labor unions hesitated to choose sides between two longtime friends—Bryan and Darrow. Only a handful of small unions did so, such as the prodefense Georgia Federation of Labor. Even the nation’s two leading teachers’ organizations split. Pushed by its vice president, ACLU executive committee member Henry Linville, the smaller American Federation of Teachers adopted a resolution in support of Scopes. The larger National Education Association rejected a similar resolution as “inadvisable.”

30

Relatively little comment about the trial survives from African Americans. A few black evangelists, such as Virginia’s John Jasper, endorsed Bryan’s position, while the NAACP, which worked regularly with the ACLU, participated in some of the ACLU’s New York meetings on the trial. In any event, the outcome would not affect African Americans, because Tennessee public schools enforced strict racial segregation and offered little to black students beyond elementary instruction.

30

Relatively little comment about the trial survives from African Americans. A few black evangelists, such as Virginia’s John Jasper, endorsed Bryan’s position, while the NAACP, which worked regularly with the ACLU, participated in some of the ACLU’s New York meetings on the trial. In any event, the outcome would not affect African Americans, because Tennessee public schools enforced strict racial segregation and offered little to black students beyond elementary instruction.

White fundamentalists rushed in to fill the void, and willingly engaged modernists and evolutionists in setting the terms for public debate over the trial. In pulpits across America, conservative ministers argued against Darwinism. Many attacked Darrow and the menace of materialism as well, such as the Tennessee pastor who claimed that he “had been searching literature and the pages of history in an effort to find someone with whom he might class Darrow, but as yet had not been able to place him but in one class, and that of the Devil.”

31

Leading antievolution crusaders such as Riley, Norris, Straton, Martin, and Sunday redoubled their efforts in the days before the trial, barnstorming the country for creationism. On a train to Seattle, Norris wrote to Bryan, “It is the greatest opportunity ever presented to educate the public, and will accomplish more than ten years campaigning.”

32

From Oregon, Sunday added his endorsement of “any views expressed by William Jennings Bryan.”

33

Summer having come, the Bible conference and Chautauqua seasons were in full swing, providing ready audiences of antievolutionists.

31

Leading antievolution crusaders such as Riley, Norris, Straton, Martin, and Sunday redoubled their efforts in the days before the trial, barnstorming the country for creationism. On a train to Seattle, Norris wrote to Bryan, “It is the greatest opportunity ever presented to educate the public, and will accomplish more than ten years campaigning.”

32

From Oregon, Sunday added his endorsement of “any views expressed by William Jennings Bryan.”

33

Summer having come, the Bible conference and Chautauqua seasons were in full swing, providing ready audiences of antievolutionists.

During the twenties, the public became fascinated by formal debates between proponents and opponents of the theory and teaching of evolution. In 1924, for example, Straton and Potter clashed over the theory before a large audience at Carnegie Hall in a debate broadcast live on the radio and subsequently published by a commercial press. A panel of three judges from the New York State Supreme Court gave a unanimous decision to Straton on technical merit. “With the exception of the legal battles to outlaw evolution or to get ‘scientific creationism’ into the public schools,” the historian Ronald Numbers observed, “nothing brought more attention to creationists than their debates with prominent evolutionists.”

34

Public interest in the coming trial generated a variety of such debates across the country, including a series between Riley and the science popularizer Maynard Shipley on the West Coast. “Please report my compliments to Dr. Riley,” Bryan wrote to Straton in early June, just before Straton joined Riley for the final debate in Seattle. “He seemed to have the audience overwhelmingly with him in Los Angeles, Oakland and Portland. This is very encouraging; it shows that the ape-man hypothesis is not very strong outside the colleges and the pulpits.”

35

For the moment, at least, antievolutionists appeared to have the upper hand.

34

Public interest in the coming trial generated a variety of such debates across the country, including a series between Riley and the science popularizer Maynard Shipley on the West Coast. “Please report my compliments to Dr. Riley,” Bryan wrote to Straton in early June, just before Straton joined Riley for the final debate in Seattle. “He seemed to have the audience overwhelmingly with him in Los Angeles, Oakland and Portland. This is very encouraging; it shows that the ape-man hypothesis is not very strong outside the colleges and the pulpits.”

35

For the moment, at least, antievolutionists appeared to have the upper hand.

The presence of Riley or Straton insured a large audience, but a pair of mid-June debates in San Francisco between Shipley and two young editors of a Seventh Day Adventist journal may have attracted the greatest attention. According to the

San Francisco Examiner,

“That the Scopes trial is a living issue in San Francisco as elsewhere was indicated by the large crowd which on both evenings filled the auditorium long before the meeting hour, and afterwards filled the street and threatened to rush the doors.”

36

Prominent California jurists served on the panel of judges. Shipley spent the first debate sniping at Bryan, which allowed his Adventist opponent to win a split decision against the proposition, “Resolved, That the earth and all life upon it are the result of evolution,” by systematically raising a host of technical questions about that theory. The second debate focused on the timely issue of teaching evolution in public schools. Here Shipley gained the victory with a plea for freedom. In typical Adventist fashion, his opponent presented the teaching of evolution as “subversive of religious views” and argued for “neutrality on the questions of religion” in public schools. The remedy: “Keep evolution and Genesis both out.” Shipley countered with stories about the religious persecution of Galileo and Columbus for their scientific theories, and asserted the near universal support among scientists for the theory of evolution. “We hold that this theory, or any theory, advanced by those best qualified by education and experience to judge such matters, should be made known to the pupils of our publicly supported educational institutions, and that to suppress such knowledge is a social crime. ”

37

San Francisco Examiner,

“That the Scopes trial is a living issue in San Francisco as elsewhere was indicated by the large crowd which on both evenings filled the auditorium long before the meeting hour, and afterwards filled the street and threatened to rush the doors.”

36

Prominent California jurists served on the panel of judges. Shipley spent the first debate sniping at Bryan, which allowed his Adventist opponent to win a split decision against the proposition, “Resolved, That the earth and all life upon it are the result of evolution,” by systematically raising a host of technical questions about that theory. The second debate focused on the timely issue of teaching evolution in public schools. Here Shipley gained the victory with a plea for freedom. In typical Adventist fashion, his opponent presented the teaching of evolution as “subversive of religious views” and argued for “neutrality on the questions of religion” in public schools. The remedy: “Keep evolution and Genesis both out.” Shipley countered with stories about the religious persecution of Galileo and Columbus for their scientific theories, and asserted the near universal support among scientists for the theory of evolution. “We hold that this theory, or any theory, advanced by those best qualified by education and experience to judge such matters, should be made known to the pupils of our publicly supported educational institutions, and that to suppress such knowledge is a social crime. ”

37

The results of the San Francisco debates suggested that, in the spirit of liberty, people who doubted the theory of evolution might still tolerate the teaching of evolution. Perhaps Bryan sensed this all along and only campaigned to prohibit the teaching of evolution

as true;

but now he had to defend a broader law that barred all teaching about human evolution, while the defense followed Shipley’s approach by pleading for individual liberty to learn and teach about scientific theories.

as true;

but now he had to defend a broader law that barred all teaching about human evolution, while the defense followed Shipley’s approach by pleading for individual liberty to learn and teach about scientific theories.

Despite strenuous efforts to reach the public through debates and addresses, Scopes’s opponents regularly complained that the press garbled their message—reflecting in part their own perceptions. Following the San Francisco debates, for example, the Adventist science educator George McCready Price wrote to Bryan, “Our side whipped Mr. Shipley ‘to the frazzle.’ ” Yet newspaper reports were mixed, as were neutral judges’ and audience reactions; even an accurate news account of antievolution arguments might not sound as good as proponents remembered them. Accordingly, Price directed Bryan to “the full report of the debate” as published by an Adventist press.

38

In a private letter written shortly before the Scopes trial, Bryan explained his criticism of the press regarding the antievolution controversy. “I think the newspapers desire to be truthful about matters of science. Whether they are thoroughly sensible depends a good deal upon one’s point of view,” he commented. “I do not consider it thoroughly sensible for a paper to publish as if true every wild guess made by a man who calls himself a scientist; and yet the wilder the guess the more likely it is to be published.”

39

38

In a private letter written shortly before the Scopes trial, Bryan explained his criticism of the press regarding the antievolution controversy. “I think the newspapers desire to be truthful about matters of science. Whether they are thoroughly sensible depends a good deal upon one’s point of view,” he commented. “I do not consider it thoroughly sensible for a paper to publish as if true every wild guess made by a man who calls himself a scientist; and yet the wilder the guess the more likely it is to be published.”

39

In fact, some bias against the prosecution did taint the news coverage. Most major American newspapers went on record favoring the defense. Even within Tennessee—although editorialists roundly criticized Dayton for staging the trial and several of them grudgingly conceded that the court should enforce the law—only one major daily newspaper, the Memphis

Commercial Appeal,

consistently supported the prosecution. Surveying the initial press commentary, a

Nashville Banner

editorialist observed that “There are vigorous champions of the right of the state to regulate its institutions, but a great many editors commenting insist that the question is whether truth shall be limited by law. Inevitably Mr. Bryan has become something of the storm center.” During the trial, an article in a trade publication for journalists commented, “Some of the reporters are writing controversial matter, arguing the case, asserting that civilization is on trial. The average news writer is trying to stick to the facts as revealed in court, but it is a slippery, tricky job at best.”

40

Based on a later study of editorial and news articles from the period, the journalism professor Edward Caudill agreed: “The press was biased in favor of Darrow,” but mostly due to its insensitivity to faith-based arguments rather than to intentional advocacy.

41

Commercial Appeal,

consistently supported the prosecution. Surveying the initial press commentary, a

Nashville Banner

editorialist observed that “There are vigorous champions of the right of the state to regulate its institutions, but a great many editors commenting insist that the question is whether truth shall be limited by law. Inevitably Mr. Bryan has become something of the storm center.” During the trial, an article in a trade publication for journalists commented, “Some of the reporters are writing controversial matter, arguing the case, asserting that civilization is on trial. The average news writer is trying to stick to the facts as revealed in court, but it is a slippery, tricky job at best.”

40

Based on a later study of editorial and news articles from the period, the journalism professor Edward Caudill agreed: “The press was biased in favor of Darrow,” but mostly due to its insensitivity to faith-based arguments rather than to intentional advocacy.

41

Other books

Tenth of December by George Saunders

The Victorious Opposition by Harry Turtledove

Three Card Monte (The Martian Alliance) by Gini Koch

You Don't Know Me by Susan May Warren

The Etruscan Net by Michael Gilbert

This Could Be Rock 'N' Roll by Tim Roux

The Almond Blossom Appreciation Society by Chris Stewart

Sparks Fly by Lucy Kevin

Her Brother's Best Friend by Sarah Daltry

The Lemon Table by Julian Barnes