Sudden Sea (2 page)

For a brief time, Jamestown basked in the reflected glow. Hotels and guesthouses that could accommodate more than one thousand lined its east harbor, just a short ferry ride from Newport. The poshest spot, the 113-room Thorndike Hotel, boasted hot baths on every floor, electric lights, and a hydraulic lift. Summer rentals on the island soared. Prices ranged from $125 a season for a bungalow to $1,500 for a ten-room house with an ocean view. Some enterprising islanders moved out of their homes to cash in on the summer trade. Such Main Line Philadelphians as Charles and William Wharton, who shunned the gaudy excess of Newport, discovered the harmony of Jamestown and built splendid summer mansions on stony promontories to the north and south of the village.

War and the Depression brought an end to Jamestown’s prosperity. By the end of 1938, only two summer hotels remained in service, the Bay View and the Bay Voyage. The others had been abandoned or razed. Still, summers were lively. The island had a casino, movie theater, country club, yacht club, tennis courts, and an eighteen-hole golf course said to rival St. Andrews in Scotland, the Yankee Stadium of golf. At Mackerel Cove there was a handsome bathing pavilion — two stories high and almost three hundred feet long, with one hundred bathhouses downstairs and a ballroom upstairs. Jazz bands played in the gazebo on Shoreby Hill in the long cool evenings. The navy’s Atlantic Fleet summered in the bay, and there was the excitement of the America’s Cup race.

Accessible only by water, Jamestown became icebound and bleak in winter. Bobsleigh rides, candy pulls, and skating parties kept the youngsters occupied. Occasionally a ship lost her bearings in the fog and wandered into Mackerel Cove, mistaking it for Newport Harbor. The ship would run aground and have to be towed. That was about as eventful as life got in the bare-boned off-season when just eking out a living was a struggle. But this was September, the optimal time of year. The weather was fine, and the islanders were free, flush, and filled with a proprietary feeling as they reclaimed their island, and their children returned to school.

The sun was burning off the morning haze when the Jamestown school bus pulled up at the Beavertail light. Norm Caswell picked up the Chellis kids, then stopped at one of the summer fishing camps clustered along the rocky shore for the Gianitis boys. His final stop on this run would be Fox Hill Farm. There was only one school bus for the island, and Norm made two loops each morning and afternoon, one to Beavertail, the other to the far north end. He dropped off the high school kids in town so they could catch the ferry to Newport, then swung up Narragansett Avenue, the main commercial street, to North Road. Jamestown had two schools there, a block apart — Clarke School, a square, one-story brick middle school, and the Carr School, a shingled elementary school with a pretty bell tower.

Though not one of the original founding families, the Caswells had lived on the island for generations. They were an enterprising lot. Norm’s grandfather was the last of the sail-ferry captains, and his uncle Philip was among the first to capitalize on Jamestown’s natural charms. In the 1860s Philip Caswell and his brother John, both druggists, moved to Newport, where they met a man named Massey and formed a toiletries company. The firm of Caswell-Massey moved to New York and prospered beyond their wildest dreams. When Philip Caswell returned to Rhode Island, he was a wealthy man. By then, Newport had been transformed from a small port into a grand resort. Looking across the bay to the unspoiled island of his birth, Caswell saw a golden opportunity. He bought 240 acres south of the ferry dock, divided the land into plots, and sold the sites for summer cottages. Another Caswell devised a bus to transport the ferry passengers that swarmed over from Newport.

Norm Caswell kept up the family tradition, after a fashion. When he wasn’t driving the school bus or fishing with his brothers, Connie and Earl, Norm ran Caswell Express, a local delivery service, down by the Jamestown-to-Newport ferry slip. Business was solid all summer — best in June and September, when the summer people were shipping their trunks. Norm probably did as much business in those two months as he did in the other ten. Once the summer folk went back to Philadelphia and St. Louis, the wealth on the island dropped like an anchor in the bay. Norm was a good sort, not a man of towering ambition but amiable and reliable. In his mid-forties, a father of three, he was popular with all the children who rode the school bus.

Joseph Matoes Jr. stretched, bending his shoulders back to ease the cramp that was forming, and squinted into the distance, hoping the flash of yellow at the edge of the pasture was just an oriole. It was the tenth day of a new school year, and the boy had been up since first light helping his father with the haying. The yellow flash was growing, rumbling up the road toward the farm. He would have to finish the job after school. Across the fields domes of hay loomed like primitive burial mounds through the breaking mist. Cows grazed in the meadows that rolled to the edge of Mackerel Cove, and low dividing walls no higher than three feet — stone on stone, gathered from the fields and rocky coast and piled one on top of the other — drew a grid across the fields. Joseph started in, not so much reluctant as resigned. It had rained for days, and the pastures were mud baths, pitted with puddles, some as big as ponds. His thigh-high rubber boots were encrusted.

Joseph was tall, a good head taller than anyone else in his class, and handsome, although he didn’t realize it. He had black curly hair, soft dark eyes, and wind-dark skin from working outside in every weather. He looked like a teenage Clark Gable, but there was a sadness that seemed a part of him, like salt in sea air. Joseph was too old to be in sixth grade, but he was not much of a student. He didn’t have time for schoolwork — or for much of anything else except the farm. So he kept to himself, went to school, and worked on the farm: school, farm, school, farm. His father depended on him. He was the only son in a family of seven. The Matoeses rented the pastures of Fox Hill Farm and the small tenant farmhouse across the road from the gambrel-roofed main house. Joe Sr. and his second wife, Lily, had both been widowed when they met, and their combined families included Joe’s three children — Joseph Jr., fourteen; Mary, seventeen; and Theresa, ten — Lily’s daughter Dorothy, known as Dotty, also ten; and Joe and Lily’s daughter, Eunice, seven.

Joseph’s future seemed certain, circumscribed by the shores of the island. When he finished eighth grade, he would work on the farm full-time with his father, and if he married, the reception would be held at the Holy Ghost Hall over on Narragansett Avenue. The social hall was the hub of Portuguese life on the island.

Sometime in the 1880s, Portuguese families had begun settling in New England coastal towns, from New Bedford to New London, forming close, self-contained neighborhoods. Those who came to Jamestown, mainly fishermen, gardeners, and tenant farmers like the Matoeses, were mostly from the Azores. They were drawn by the island’s geography, which reminded them of the old country.

Although everyone knew everyone, island life was stratified according to ethnic and religious lines. The Portuguese, almost entirely Roman Catholic, had their own grocery store, Midway Market, owned by Joe Matoes’s brother Manny, and socialized together at the Holy Ghost Hall. The Portuguese had a special devotion, and in June they celebrated the Feast of the Holy Ghost with a daylong

festa.

There was food, music, dancing, cotton candy for the kids, and a procession through the town carrying a sterling silver filigreed crown representing the Holy Ghost. The silver crown was the community’s prize possession. It was an honor to be chosen to keep the crown through the year.

Except for the Portuguese, most of Jamestown’s year-round residents were WASPs, many descended from the founding families. They were land-rich and cash-poor, and like Norm Caswell, they got through the off-season on the money they made from the summer trade. As one of them put it, “We were awful glad to see the summer folk come in June, and we were awful glad to see them go in September.” Like most coastal towns of southern New England during the tough Depression era, Jamestown had three groups: the haves, who were the summer people; the have-nots, the year-round people; and the dirt-poor.

The school bus pulled up beside the Matoes house at Fox Hill Farm and the three girls trooped out. Waving to Norm, Joseph crossed the road and went into the barn to take off his boots. He could hear his stepmother yelling at him to hurry up; he was making his sisters late for school.

Lily Matoes was always yelling at her stepchildren. Her features were as sharp as her voice, and her hair was witch-black. Joseph and his sisters Mary and Theresa took care of one another and kept out of their stepmother’s way as much as they could. It was hardest for Mary, seventeen and home all day working in the house. Mary had been a straight-A student, at the top of her class in grammar school, but Lily didn’t believe a girl needed more schooling. She wouldn’t allow Mary to go on to high school and couldn’t see any reason to waste good money on a graduation dress. Mary’s aunts had intervened, and she graduated in a white dress worn the year before by a cousin. It was a bittersweet day.

Mary remembered their mother clearly. Joseph was only five when she died. In his imagination, Rose was as beautiful as her name. He liked to picture her at the back door, calling him in for supper, her voice as light as a summer breeze, or leaning over his bed to kiss him good night, her hand on his forehead, pushing his hair back. All he had were fragments — a touch, a look, an endearment. They could have been dreams as easily as true memories. Although her absence was a permanent part of each day, he was never sure whether he was remembering his mother or the stories Mary told him.

Joseph stopped at the pump to wash his hands and throw some water on his face, then climbed on the bus, tired before the school day had begun. His sisters were sitting together. Theresa was the prettiest girl in the sixth grade — everyone said she looked like Rose — and Dotty was as bright as the morning in a new red skirt and white blouse. Eunice, still the baby at seven, was sitting with Marion Chellis. They looked like Rose Red and Snow White. The two little Greek boys, Constantine and John Gianitis, sat together in the front seat, silent and solemn-faced. They knew only a few words of English. Clayton Chellis was sprawled across the backseat with his brother, Bill. Clayton, Joseph, Theresa, and Dorothy were all in the sixth grade. Clayton was the ringleader of the boys, a hellion and utterly fearless, not a nerve in his body.

Norm Caswell pulled a U-turn. The sweet smell of the newly cut hay trailed the school bus as it rolled back down the farm road, and mixed with the sea smells rising from Mackerel Cove. As the bus turned from Fox Hill Farm onto the causeway that links the two parts of the island, long swells were forming far out in Narragansett Bay and bright sunshine shimmered off the roof of the beach pavilion. School should be forbidden on such a perfect day.

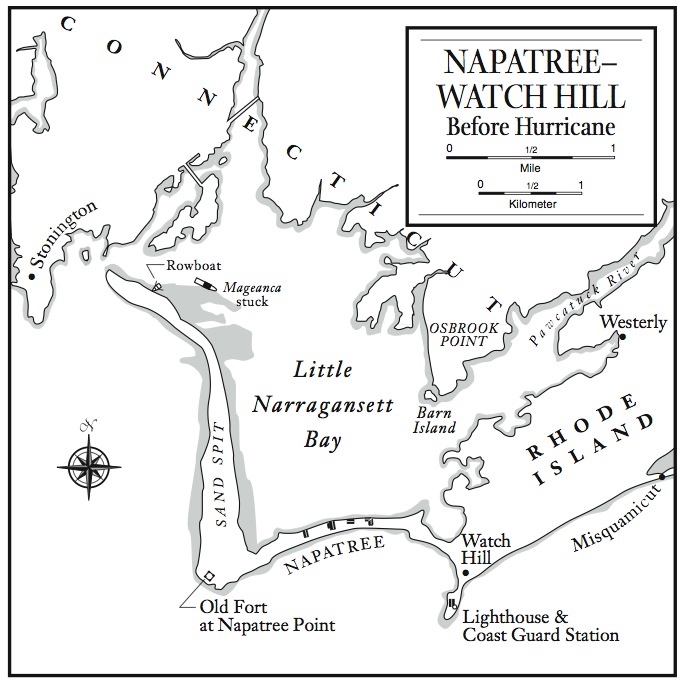

At the western point of Rhode Island, along Napatree, a pair of sandpipers raced the tide, darting after the ebbing water, skittering in and out so fast their black stick legs blurred like lines of ink, so light their feet left only scratch marks on the sand. The west-ernmost spit of land in Rhode Island, Napatree is a scythe of barrier beach that juts from the tony resort of Watch Hill, its face to the open Atlantic, its back to Little Narragansett Bay. At the eastern end a breakwater protects the yacht club and beach club, and in the distance the Watch Hill estates rise like summer castles. In 1938 a rocky beach and abandoned fort guarded the far point, and curving west from the fort stretched another mile or so of open beach that residents called the sand spit.

Lillian Tetlow and Jack Kinney trailed the pipers, walking hand in hand at the edge of the surf. Lillian was seventeen, small-boned and delicate. She had been born in England and retained the suggestion of an accent, although her family had emigrated when she was a child. Jack was twenty-three, a shade under six feet, with good shoulders and a smile that said she was the only girl in the world for him.

Lillian had never been to Napatree before, and she turned back to admire the row of summer houses that lined the beach, thirty-nine strong, as gracious if not quite as splendid as their Watch Hill neighbors. They were two and three stories of weathered shingles, their broad front porches a few strides from the Atlantic. Cement walls, three, maybe four feet high, protected them from the sea’s darker moods. On the bay side across the single narrow blacktop called Fort Road, a private dock extended behind almost every house. The younger children practiced swimming by paddling from one dock to the next.

Lillian and Jack strolled toward the western point. Beyond, where the beach crested, dune grass swayed in the freshening breeze. The sun was high, and at the horizon, slivers of light reached down, touching the single sail that sat off the point and the buoy that marked the bay entrance. They passed a couple of clammers on their way out, brothers-in-law from Pawcatuck, their big buckets almost full of quahogs and littlenecks. Otherwise, they had the beach to themselves. The sea was running high. Long rollers formed far out and swept in, crashing onto the beach. Lillian and Jack darted in and out of the breakers like the birds, splashing water at each other and shrieking when a shower of spray caught them, young lovers on a sandy beach, whiling away a perfect September day.