Streets of Gold (19 page)

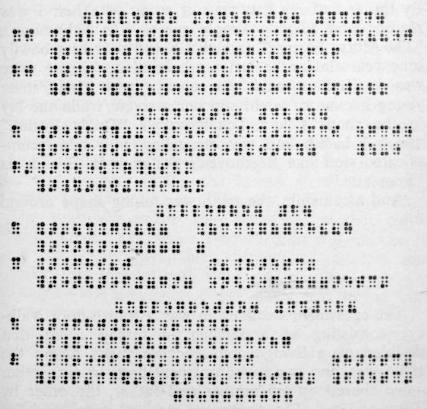

I’ve been told by sighted people who are not musicians that those sixteenth notes in the bass clef of the first and second measures look forbidding, as do the triplets in the treble clef of the last two measures. But believe me, this is a

very

simple exercise. Well, here’s that same passage as it would look (or, more correctly,

feel

) in Braille:

very

simple exercise. Well, here’s that same passage as it would look (or, more correctly,

feel

) in Braille:

Try, then, to imagine the Braille notation for a beast like the “Hammerklavier.” The mind boggles. And mine

did

. In fact, I

still

find Braille music confusing at times, even though I studied it for the better part of ten years. Space is a problem in music for the blind, and very often the same symbols are used to mean different things. Imagine being a blind musician for a moment (thank God, you don’t

have

to) and running across a symbol that stands for a whole note as well as an eighth note. Rampant bewilderment?

I

tell

you

. Or stumble across a shorthand musical direction that says, “Count back twelve measures and repeat the first four of them.” Dandy, huh?

did

. In fact, I

still

find Braille music confusing at times, even though I studied it for the better part of ten years. Space is a problem in music for the blind, and very often the same symbols are used to mean different things. Imagine being a blind musician for a moment (thank God, you don’t

have

to) and running across a symbol that stands for a whole note as well as an eighth note. Rampant bewilderment?

I

tell

you

. Or stumble across a shorthand musical direction that says, “Count back twelve measures and repeat the first four of them.” Dandy, huh?

Patiently, Miss Goodbody taught me to read. I memorized the keyboard, I memorized the chords, I memorized pieces in Braille, feeling the raised dots with one hand while I played the notes with the other, and then reversing the process with the other hand. By the end of my first year of study with her, I was reading and playing simple pieces like Schumann’s “The Merry Farmer” (which I heard sung as a bawdy tune years later, the lyrics proclaiming: “There once was an Indian maid/who always was afraid/some young buckaroo/would slip her a screw/while she lay in the shade”) and Tchaikovsky’s “Doll’s Burial,” which I hated, and was struggling with more complicated stuff like Beethoven’s Sonatina in G and his “Ecossaise.”

And meanwhile, the myth was taking shape around me.

The apartment we lived in was a fourth-floor walk-up, consisting of a kitchen, a dining room that doubled as a living room because that’s where the radio was, and two bedrooms next door to each other — one shared by my mother and father, the other by Tony and me. The apartment was not a railroad flat in the strictest sense. That is, the rooms were not stretched out in a single straight line, like train tracks. But it

was

a railroad flat in that there were no interior corridors, and to get to one room you had to pass through another. My parents must have made love very tiptoe carefully, lest Tony or I, on the way to the bathroom in the dead of night, stumble upon their ecstasy. The kitchen was tiny, with the icebox, the gas range, and the sink lined up against one wall, a wooden table with an oilcloth cover (I

loved

the feel and the smell of that oilcloth) against the opposite wall. A window opened onto the backyard clotheslines, and also onto the windows of countless neighbors with whom, like an Italian (excuse me — American) Molly Goldberg, my mother held many shouted conversations as she hung out the laundry.

was

a railroad flat in that there were no interior corridors, and to get to one room you had to pass through another. My parents must have made love very tiptoe carefully, lest Tony or I, on the way to the bathroom in the dead of night, stumble upon their ecstasy. The kitchen was tiny, with the icebox, the gas range, and the sink lined up against one wall, a wooden table with an oilcloth cover (I

loved

the feel and the smell of that oilcloth) against the opposite wall. A window opened onto the backyard clotheslines, and also onto the windows of countless neighbors with whom, like an Italian (excuse me — American) Molly Goldberg, my mother held many shouted conversations as she hung out the laundry.

Molly Goldberg was part of the growing myth.

We needed that myth in the thirties. We needed it because we were desperate. I used to think my mother was a lousy cook. I used to think her menus were unimaginative. I can still recite the entire menu for any given week from 1933 through 1937, because they didn’t change an iota until my father was appointed a regular and we moved to the Bronx. We began eating a little better then. But in those years when he was bringing home his twelve dollars a week from the post office (plus eight cents a letter for special delivery mail), the menus were unvaried. I knew, for example, that Monday night meant soup. The soup was made with what my mother called “soup meat,” and which I now realize was the cheapest cut of beef available, stringy and tasteless, and boiled in a big pot with soup greens and carrots. On Tuesday and Thursday nights, pasta was served with a meatless sauce, spiced and herbed, accompanied by salad and bread. On Wednesday night, we ate scrambled eggs with bacon. Eggs cost twenty-nine cents a dozen in those days, but my mother used only eight of them with a pound of bacon (at twenty-two cents a pound) and could serve a dinner for four, including Italian bread and an oil-and-vinegar salad, for about fifty-two cents. Friday night was fish, of course. On Saturday night, we ate breaded veal cutlets. Veal cost sixteen cents a pound as opposed to twenty cents a pound for pork or twenty-six cents a pound for round steak. On Sunday, we went to my grandfather’s house for the weekly feast. We were not starving. I don’t mean to suggest we were even hungry. I’m only saying that we (not me, not Tony, but certainly my parents) were aware of our plight, and further aware that millions of other Americans

were

hungry and

were

starving.

were

hungry and

were

starving.

In 1932, the wife of President Hoover had said, “If all who just happened not to suffer this year would just be friendly and neighborly with all those who just happened to have bad luck, we’d all get along better.” Maybe

she

started the myth, who the hell knows? Or maybe it was Hoover’s Secretary of Labor who, again in 1932, while people were aimlessly wandering the nation in boxcars and eating roots in barren fields, said, “The worst is over without a doubt, and it has been a disciplinary, and in some ways, a constructive experience.” Well, by 1933, the worst was still far from being over without a doubt, and everyone in the country knew that whereas some people had it slightly better than

other

people,

everybody

had it bad. We’d been riding high on those fat years following World War I, and suddenly, literally overnight, we’d fallen into an abyss so deep it appeared bottomless. We rushed to elect Roosevelt in 1932, not because we thought he’d miraculously pull us up into the clear blue yonder, but only because we thought he might somehow arrest our downward plunge before we hit the jagged rocks below. And now it was 1933, and FDR and the NRA and the CCC and the PWA and the WPA and the AAA had given us a whole lot of alphabets, but still not much soup to put them in. “Hard times” was

still

the common denominator; without that specter of hunger constantly leering in the background, the myth would never have come into being.

she

started the myth, who the hell knows? Or maybe it was Hoover’s Secretary of Labor who, again in 1932, while people were aimlessly wandering the nation in boxcars and eating roots in barren fields, said, “The worst is over without a doubt, and it has been a disciplinary, and in some ways, a constructive experience.” Well, by 1933, the worst was still far from being over without a doubt, and everyone in the country knew that whereas some people had it slightly better than

other

people,

everybody

had it bad. We’d been riding high on those fat years following World War I, and suddenly, literally overnight, we’d fallen into an abyss so deep it appeared bottomless. We rushed to elect Roosevelt in 1932, not because we thought he’d miraculously pull us up into the clear blue yonder, but only because we thought he might somehow arrest our downward plunge before we hit the jagged rocks below. And now it was 1933, and FDR and the NRA and the CCC and the PWA and the WPA and the AAA had given us a whole lot of alphabets, but still not much soup to put them in. “Hard times” was

still

the common denominator; without that specter of hunger constantly leering in the background, the myth would never have come into being.

If Hoover’s woman had naively stated one element essential to the creation of any myth in any time (a cultural ideal), and if Hoover’s man had optimistically stated another (a commonly felt emotion or experience), it was Franklin Delano Roosevelt who became the first of literally thousands of thirties’ heroes (or villains) without which the myth could not have functioned. Everybody either hated him or loved him. There was no in between. You never heard anyone saying, I can take the man or leave him alone. He was “

That

Man,” and there was no possible way of remaining indifferent to him or his programs. But if love and hate are opposite sides of the same coin, and you spin the coin often enough and fast enough, the emotions become blurred and all you know is that something’s spinning on the table there, and it’s got two sides to it, and you can’t remember anymore which side was love and which was hate. Hating Roosevelt or loving Roosevelt became almost identical emotions. But more important, in terms of the myth, they became commonly

shared

emotions. Love him or hate him, he was ours. Deliverer or nemesis, he was ours. Thinking about him one way or the other, or both ways, or now one way and then the other, became part of what it meant to be American. We were becoming American, you see. Not the way my grandfather had (he still

wasn’t

in 1933, as a matter of fact) or the way my mother had, but in a way that was entirely new and unexpected and naive and exciting and sometimes deliriously exhilarating. We were beginning to claim people and things as our

own

, establishing tradition where earlier there had been only history to hold us together. The building blocks of the burgeoning myth were Buck Rogers guns and Charlie McCarthy insults, Busby Berkeley spectaculars and John Dillinger stickups, “Life Is Just a Bowl of Cherries,” Shirley Temple dolls, “Happy Days Are Here Again.” They

were

here again. For the first time. Because however superficial it may seem now, the myth had been conceived innocently and in desperation, and it is no accident that people today look back upon those terrible years of the 1930s with a sense of keen nostalgia. It was then that we became a family.

That

Man,” and there was no possible way of remaining indifferent to him or his programs. But if love and hate are opposite sides of the same coin, and you spin the coin often enough and fast enough, the emotions become blurred and all you know is that something’s spinning on the table there, and it’s got two sides to it, and you can’t remember anymore which side was love and which was hate. Hating Roosevelt or loving Roosevelt became almost identical emotions. But more important, in terms of the myth, they became commonly

shared

emotions. Love him or hate him, he was ours. Deliverer or nemesis, he was ours. Thinking about him one way or the other, or both ways, or now one way and then the other, became part of what it meant to be American. We were becoming American, you see. Not the way my grandfather had (he still

wasn’t

in 1933, as a matter of fact) or the way my mother had, but in a way that was entirely new and unexpected and naive and exciting and sometimes deliriously exhilarating. We were beginning to claim people and things as our

own

, establishing tradition where earlier there had been only history to hold us together. The building blocks of the burgeoning myth were Buck Rogers guns and Charlie McCarthy insults, Busby Berkeley spectaculars and John Dillinger stickups, “Life Is Just a Bowl of Cherries,” Shirley Temple dolls, “Happy Days Are Here Again.” They

were

here again. For the first time. Because however superficial it may seem now, the myth had been conceived innocently and in desperation, and it is no accident that people today look back upon those terrible years of the 1930s with a sense of keen nostalgia. It was then that we became a family.

“I think

we’re

gonna have to march, too,” my father said. “If we can’t get a decent living wage, Stella, we have to march.”

we’re

gonna have to march, too,” my father said. “If we can’t get a decent living wage, Stella, we have to march.”

“How can government employees march?” my mother asked.

“It won’t be the same as a strike. It’s just a way of letting them know we’re alive.”

“You know what Grandpa told me this afternoon?” I said.

“What did Grandpa tell you?”

“That Mussolini is right about Ethiopia. It

does

belong to the Italian people.”

does

belong to the Italian people.”

“Sure, your grandfather’s a greaseball,” my mother said. “What do you expect him to say?”

“He’s not a greaseball no more,” Tony said. “He’s been here more than thirty years already.”

“Can he run for president?” my mother asked.

“No, but...”

“Then he’s still a greaseball,” she said flatly.

“

I

can run for president,” I said. “And Tony can, too.”

I

can run for president,” I said. “And Tony can, too.”

“Why don’t you run together?” my mother said, not without a touch of sarcasm. “President and vice-president.”

“Would it be any worse than Roosevelt and Garner?” my father asked, and then said, “How come fish again?”

“It’s Friday,” my mother said.

“I hate fish,” my father said.

“So do I,” Tony said.

“Me, too,” I said.

“That’s right, teach them to be heathens,” my mother said.

“Miss Goodbody says Mussolini is a bad man,” I said.

“Is she a Jew?” my father asked.

“I don’t know. Why?”

“Because the Jews are for Ethiopia.”

“Grandpa says Roosevelt is a Jew,” Tony said.

“Another one of his greaseball ideas,” my mother said. “I get sick and tired of hearing him talk about the other side all the time. If he likes it so much there, why the hell doesn’t he go back?”

“He

is

going back,” I said. “And I’m going with him.”

is

going back,” I said. “And I’m going with him.”

“Here’s your hat, what’s your hurry?” my mother said.

“The streets are so clean in Fiormonte, you could eat right off them,” Tony said.

“Try eating off your plate right here, why don’t you?”

“In Fiormonte, everybody’s poor but happy,” I said.

“Sure, that’s why your grandfather came here. Because everybody was so happy in Fiormonte.”

“He came here to make his fortune,” Tony said.

“So he made it. So tell him to shut up about the other side.”

“Vinny the Mutt hit the numbers for five hundred bucks the other day,” my father said. “Now

that’s

a fortune.”

that’s

a fortune.”

“Miss Goodbody says the numbers is a racket,” I said. “What time is it?”

“Seven o’clock.”

“ ‘Amos ’n’ Andy’!” I yelled, and shoved back my chair, and ran into the dining room. “She says it supports prostitution.”

Radio was the best entertainment medium ever devised for humanity. I am one day going to form a blind men’s marching society, and we are going to begin screaming at the tops of our lungs outside movie theaters and television studios, demanding the abolition of any form of entertainment that requires the use of eyes. If you yourself are blind and reading this in Braille (fat chance) or having it read aloud to you by someone who will undoubtedly distort its tonal quality, please consider seriously the possibility of joining this lonely voice, and forming (in the tried-and-true American way) a group that will demand something vitally important in its own tiny, selfish way — the return of the radio as something more than a conduit for bad music and bad news. We will be the only

true

minority group on these shores; the

smallest

one, anyway.

true

minority group on these shores; the

smallest

one, anyway.

Calling ourselves the Consolidated Organization to Correct Kinescopic Excesses, Yelling to Eliminate Discrimination to the Sightless, we will become known in brief (and again in keeping with the American way of reducing long titles to acronyms) as the COCK-EYEDS. And having a title, and a shorthand word representing that title, we will then be able to take our place alongside all those other organizations shouting for separateness and apartness instead of solidarity-proud, worthy, and righteous conclaves like the Brotherhood of Abortion Banners Insisting on Egg Survival; or the Regional Independent Federation of Lovers of Egret Shooting; or the American Readiness Association Clamoring to Halt the Nasty and Intolerable Destruction of Spiders; or, finally, the Committee Against Virtually Everything Stalagmitic. And one day, all of us will happen to meet in the middle of Fifth Avenue, marching in all directions, and we will shout, “Brother!” together at the same instant, mistaking this for a cry of unity instead of an echo in a closed, locked, windowless room. On that day, we will finally discover we’d all been blind. I should only live to see it.

Other books

Senshi (A Katana Novel) by Cole Gibsen

Otis Spofford by Beverly Cleary

Bolted by Meg Benjamin

Pretty When She Destroys by Rhiannon Frater

The Housewife Assassin's Deadly Dossier by Josie Brown

The Killing Sea by Richard Lewis

Batavia by Peter Fitzsimons

Secrets of My Hollywood Life: Family Affairs by Jen Calonita

Breathe: A Novel by Kate Bishop

Angels and Djinn, Book 3: Zariel's Doom by Lewis, Joseph Robert