Strange Light Afar (4 page)

Read Strange Light Afar Online

Authors: Rui Umezawa

“You see, I am no longer of this mortal world. What you see in front of you is the spirit of a dead man.”

Samon blinked, unsure if he had heard correctly. Yet the more carefully he looked at the figure in front of him, the more he understood that this was true. Akana's body was subtly translucent, and his

ki

was very weak, like a dying breath of incense.

Something sharp and hot cut into the young samurai's eyelids as tears welled over.

“How can this be?”

Akana, however, seemed relieved. He gradually told his account, resting often, as though speaking were an immense burden.

He recounted how, when he arrived back home, he found that Lord Tsunehisa had firmly established his grip over the region. Akana's friends and acquaintances who were alive had all sworn their allegiance to Tsunehisa, while the few who defied him had been summarily executed.

“I called upon my cousin Tanji. He was very surprised to see me, as he assumed I had perished during my travels. We discussed at length how we might honor our late lord, but he was convinced Tsunehisa had grown too powerful. He himself had been at a loss as to what to do when he was offered a chance to resume his job as chief instructor of the classics.

“I became curious as to how Tsunehisa had amassed such a loyal following in such a short time. I wanted to meet the man to assess him with my own eyes, so I asked Tanji to arrange a meeting. Given an audience in Tomita Castle, I immediately realized Tsunehisa was a fierce and courageous warrior. We spoke for an hour, and I found his only flaw was the paranoid way he suspected everyone around him.

“He was extremely loyal to those who served him well, however, and I could not perceive any weakness in either himself or in the relationship he held with his trusted generals. There was, I concluded, nothing to be done, so I politely asked to be given leave.

“The lord of the castle then exchanged a glance with my cousin, and I immediately knew that they had been communicating about me and that something was amiss. Suddenly, Tsunehisa ordered his guards to seize me, accusing me of treason. He said my intention to take control of his castle had been conveyed to him beforehand by my cousin.”

Akana shook his head angrily. “Tanji is a fool. He believed I had returned to exact vengeance for Kamon or to compete for Tsunehisa's favors. Either way, he felt it best to remove me from this world.

“They tortured me for several hours each day, then threw me into a cell at night. They whipped my back raw and pressed hot iron against my chest to force me to confess to a crime I had had no intention of committing. None of this was important, however. What mattered to me most was that I might not be able to return here at the promised time. What would you think of me then? How disappointed would you be with me? I could not stand to think of this.

“But since ancient times, it has been known that even if a physical body could not travel a thousand leagues in a day, a spirit can do so readily. Recalling this, I knew what must be done. I would have preferred to die by the swordÂ

â

my own if no one else's, but they had taken my weapons from me. Fortunately, they had given me chopsticks with which to eat my meals. I pushed one of them through my throat and drowned in my own blood.”

Samon closed his eyes and shook the image from his mind. They say both samurai sat wordlessly for a long time, their faces wet with tears.

“Take pity on me, brother,” said Akana. “But know that I was at least able to keep my promise to youÂ

â

that I never strayed from the path of honor.”

The ghost stood and smiled. “And, if nothing else, I was able to see you this last time to engrave your face onto my memory for eternity. Please convey my respect and my best wishes to our mother. Take good care of her ⦠and of yourself.”

Samon was gripped by panic when he saw his blood brother's body dissolving. He would only recall afterwards that Akana still appeared forlorn in the final moments as he faded away like a dreamÂ

â

an almost tangible sadness emanating from an ethereal being.

Then he was gone.

Samon found he was unable to stop crying. He remained seated across from the empty cushion, watching the meal he had painstakingly prepared turn stale and brittle.

In the morning he told his mother what had happened. She was incredulous at first, but finally said, “Your account is so detailed that I am starting to understand that what you experienced could not have been a dream. Come. Let us light incense to pray that his spirit is now at peace.”

“I believe that prayer will not be enough to grant him peace,” said Samon, anger welling in his chest.

His mother immediately grasped Samon's meaning. Living a tranquil lifestyle, treasuring his gentle demeanor, it was easy to forget her son was a warrior. She feigned indifference and lit the candles and incense at the humble Buddhist altar placed in one corner of the hut.

Sensing that her son was torn between honoring his brother and looking after her welfare, she said quietly, “You must go. You know how he held us in such high esteem. You must honor and avenge him. Just do not be gone for long. My old heart cannot withstand too much worry.”

Samon wished that he could comfort his motherÂ

â

to vow to return just as Akana had. However, although his fate had been set since the start of time, he had no way of knowing how it would unfold.

“I shall try my best,” was all he could promise.

Being not a ghost but simply a man driven by anger, he could not fly to the province of Izumo. He hurried, however. Although hungry, he would not think of food. Although cold, he did not think of shelter. He slept in the open when needed, and even then dreamed of his brother's face and wept.

They say he made the journey in just ten days.

The autumn wind had turned crisp by the time Samon knocked on the door of Akana's cousin. Tanji was keeping company with three of the local samurai. The sour smell of alcohol hung in the mid-afternoon sun. Scattered among the four of them were trays of half-eaten delicacies and empty sake bottles. The samurai appeared as content as fatted pheasants.

“What may I do for you, esteemed sir?” Tanji asked Samon, his smile stiff with faint apprehension.

“I came to hear, in your own words, how your cousinÂ

â

my blood brotherÂ

â

came to be a prisoner in Tomita Castle. And how he came to perish in his cell.”

“How can you possibly know this? You could not have received word of it and come so quickly.”

“That is unimportant,” said Samon, crushing bitterness with his back teeth. “Tell me what happened.”

“Alas, my cousin was proven to be guilty of treason. He had returned here only to plot revenge on our Lord Tsunehisa. Fortunately, he revealed his plans to me, and I was able to foil his diabolical scheme.”

“You have revealed yourself to be a treacherous rat unworthy of my brother's trust,” said Samon. “You saw his homecoming as an opportunity to curry favors with your lord. For political and financial gain, you betrayed your own family. You have violated my brother's trust and dishonored your family's name. I have traveled without rest for ten days to come here and avenge Akana's restless spirit!”

“How dare you!” shouted Tanji, as he sprang to his feet with his sword in hand. He did not have time to draw it, however. Samon's pristine blade appeared to glide out of its scabbard, blindingly fast, tracing a smooth arc that cut through Tanji's neck. The head, still wearing an expression of false righteousness and resentment, separated from the body. A spray of blood blossomed in the air.

From the corner of his eye, Samon saw the other samurai rushing to attack as formless shadows, but this was more than enough for his honed reflexes. The one closest swung a cutting blow high enough for Samon to easily duck. His own sword changed direction as gracefully as a dancing butterfly. A killing stroke traced a path from the helpless samurai's abdomen across his chest and to his shoulder.

The remaining two came upon him too fast for him to sidestep, so he kicked one of them in the chest, making him stumble into the other. Before the samurai could regain his balance, Samon skewered his heart, then pulled away. The samurai was dead before he fell to the floor.

Fighting was now the last thing on the remaining samurai's mind. How he might beg for mercy was foremost.

“Go to your lord,” said Samon. His voice was as calm as a still lake. “Tell Tsunehisa I have no quarrel with him. He was an unknowing accomplice to Tanji's treachery. However, warn him that he should not attempt to avenge this two-faced rat, who is not worth the lives such an act would cost.”

They say this message was delivered faithfully by the samurai, who ran to the castle as fast as his weak knees would carry him. They say Tsunehisa was so impressed by the fidelity the young samurai displayed for his dead brother that he ordered that no one was to exact vengeance on behalf of Tanji or the other slain samurai. Samon was thus left alone to travel without incident back to his hut, where he and his mother lived out their days in peace.

They say Akana's spirit never appeared before them again.

FOUR

ENVY

â

L

et me stress that I stopped hitting my wife a long time ago. I also quit drinking. I tried my best to change, to be a better man and to give her all she needed. I stayed honest and maintained the small but comfortable hut in which we lived. I even visited her parents' graves.

So why?

The other women of the village whisper whenever I shuffle by. They say it's not as if she woke up one morning and decided to sleep with the old blacksmith who lives in the next town. They say it's my fault. I just sent her to have my rusted hoe repaired.

I tell my brotherÂ

â

who is about the only one who listensÂ

â

that in the end she was going to be miserable unless she left. I tell him that restraining her would do neither of us good. People were talking, so I let her go.

Jirobe shakes his head. His eyes hide behind his wrinkles when he frowns. He feels badly for me. He remarks how she's not even sent word to tell us where she is. He says I deserve better than this.

When we were kids, Jirobe's grades always topped the reading and math classes we attended at the local Buddhist temple. But I was older and bigger, so my consolation was beating him at every village sumo tournament. Once, though, I threw him harder than I'd intended, and he dislocated his shoulder.

Our father was furious. He berated me for not being more careful. He even accused me of injuring my brother intentionally. He said I was envious of Jirobe, who always helped around the house and never spoke out of turn. Father often told me I was not respectful enough. He tried to change my behavior every day with a switch across my back.

He beat me harder than usual that day, but I did not cry out even once. Funny the things you don't forget no matter how old you get. I hid the pain in a place no one would ever see.

Father never hit Jirobe. Why would he? Jirobe was respectful without being obsequious. He possessed a jubilant personality. He was also handsome.

I, on the other hand, have always been quiet and solemn. I knew better than to try to be as well liked as he. Maybe if I had, my wife would not have left me.

I never truly loved her anyway. The real love of my life is married to my brother. Sakura is often amused by how different the two of us are. I imagine she is pleased to have made the right choice by marrying him. Their wedding was a lifetime agoÂ

â

in March when the cherry blossoms, her namesake, were in full bloom along our town's main street.

I have never once told her how I feel.

Jirobe and I share the plot of land left by our father. His will divided the property down the middle. He was fair at least this once. This was the only indication that my father cared for me at all.

Every evening around suppertime, laughter swims over the hedge that divides my neglected yard from Jirobe's pristine garden. I cannot recall ever sharing a laugh with my wife that way. The days are quiet now that she's gone. At least there is a roof over my head. I have clothing and food. I've grown comfortable with the peaceful seclusion that might well be the only gift life will ever bestow upon me.

Then that dog appears out of nowhere.

Jirobe tells me that the dog took shelter by their door during last month's storm. Its fur is whiter than snow, so Sakura names it Shiro, which means “white.”

I've never been fond of animals. I hate the way they look at me. My father did not like animals, either.

The dog grows bigger each week. It runs freely in and out of their house. Shiro goes with Jirobe when he takes his vegetables to the market. I sometimes go with them, carrying what little has grown in my own yard. My brother and the dog play as they make their way down the main street. This slows them down, and I don't have the patience to wait.

Jirobe and Sakura fuss over Shiro as if it were their child.

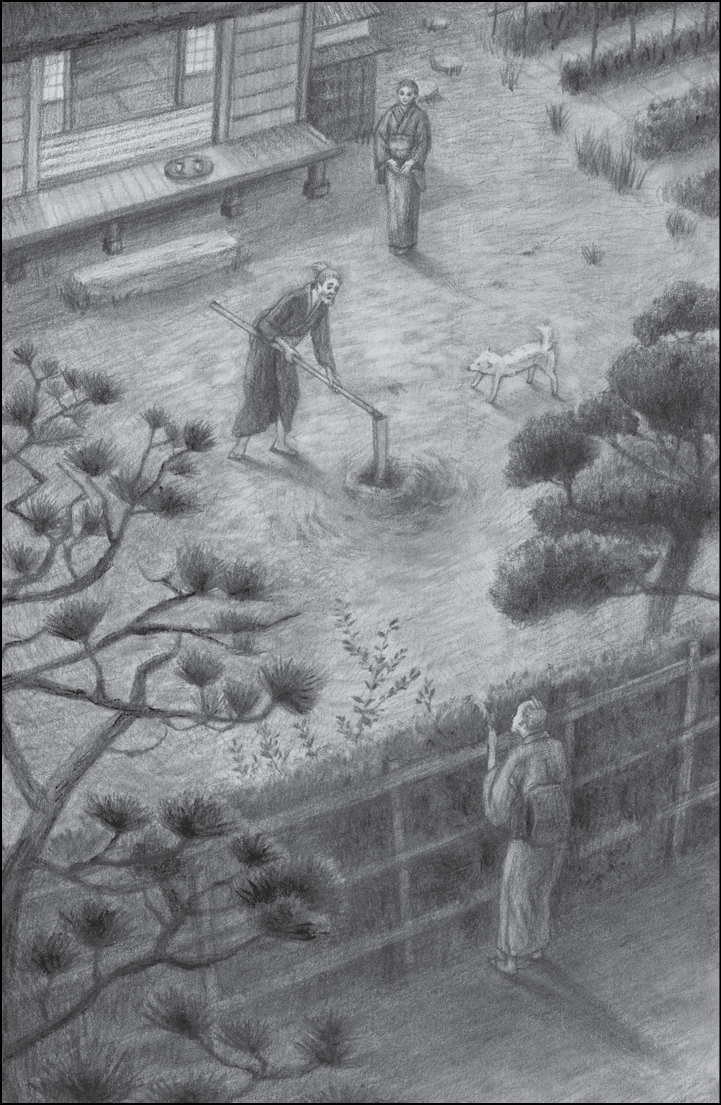

“Shiro? Shiro, what's the matter?” Jirobe frets one day when the dog doesn't stop barking in their yard.

I look over the hedge, irritated by the persistent noise.

“I think he wants us to dig here,” Sakura says. Her voice is still as clear as morning dew.

They do not notice me in my yard. I see Shiro pawing the earth that has just started to thaw after the long winter.

Jirobe brings a spade and begins to dig as I hold my breath. The hard ground breaks apart in dark, brittle morsels. Shiro keeps barking, wagging its tail, frightening the small birds that have returned with the spring.

Jirobe digs for a long time. He is old and tires quickly.

He is about to give up when the spade hits something hard. He pushes his shovel around a large, cracked earthenware pot, and when enough dirt has been cleared, he struggles to lift it.

Holding it like a fat baby in his arms, he removes the lid and peers inside. His eyes open to twice their size. Stumbling backwards, he drops the container, which shatters when it hits the ground.

Out spills forth more gold coins than anyone could possibly spend in a lifetime. Sakura puts her hand to her mouth. The dog won't stop barking, and they still do not notice that I'm watching. They gather the gold in their arms and scurry into the house. They don't bother to refill the gaping hole in the ground.

Satisfied, the dog falls silent and sniffs at what remains of the pot before lifting a leg and urinating on it.

Darkness falls early. The cold air gnaws at my toes and fingers. I don't hear the usual laughter from next door. The silence is warming, and my futon is thick and comfortable, but I can't sleep. Questions dance in my mind. I think of my father. I finger the scars on my shoulders.

He never hit Jirobe. Something hot wells behind my tired eyes and the question inevitably becomes “Why?”

Why?

In the morning, I run to my brother's house. Jirobe and Sakura seem not to have slept much, either. I ask meekly if they would lend me their dog. I say I wish to get rid of a few stray cats in my yard.

They don't mention what they found in their yard the day before. Their secret makes them comply without a fuss.

Once home, I bribe the dog with leftovers from last night's supper. I compliment it on its beautiful fur and on its cleverness. Shiro seems indifferent and ungrateful. It eats the food but pulls away when I reach out to touch it. It betrays mild curiosity when I motion for it to follow me out back.

I take hold of my spade and tell Shiro to direct me to where my treasure is buried. To where my father must have hidden my share.

To my surprise and delight, Shiro goes to a secluded corner of the yard and paws the ground.

Anticipation drives the shovel deep. My arms tire quickly, but Shiro's incessant barking eggs me on.

The spade finally hits something hard. My happy cry is heard only by the dog and the wind. I don't bother lifting the earthenware pot from the ground but simply break it open where it sits nestled in the dirt.

The mind is a powerful thing when confused. I actually for a moment see the glimmer of gold, but it immediately changes into a living, crawling darkness. The centipedes and roaches and worms and spiders crawl over each other, seeking shelter from the sudden daylight. The smell of feces twists my stomach.

The dog looks at me smugly, as if amused by this obscene, sick joke. Anger swallows confusion. The emotion is a living, breathing thing that erupts from my soul like a blisteringly hot geyser.

Shiro ignores me when I tell it to sit. The dog is sorely in need of a lesson, so I provide it by swinging my spade across its pointy ears and skull. The sound of metal hitting bone is strangely satisfying. The dog yelps and stumbles backwards.

But it still does not come when I beckon. Why won't it come? I think again of my father. Anger becomes easy, like an old friend. I shout something that I will not remember later and swing the spade again.

The more I hit the dog, the less it seems willing to do what it's told. I hit harder, over and over. And the rage becomes a pure, beautiful thing, like a pillar of blue flame. It burns on, engulfing everything before me.

After an eternity, I notice Shiro lying still on the ground. Its fur no longer resembles snow.

It's nightfall before my brother comes looking for his dog. I am spent and strangely content. Still, I'm relieved by Jirobe's appearance because I was unsure what to do with the carcass.

He can hardly keep from falling backwards when he sees the mangled, bloody heap that used to be Shiro. Shock turns into despair, then to anger and disgust. He seems to want to say something, but I'm holding the spade, dirt and blood on my hands and clothes. I may not appear quite as calm as I feel.

He carries the dog back to his house without a word.

In the morning, I see Jirobe and Sakura burying Shiro in the same hole where they found the treasure. To mark the grave, they plant a sapling so thin it looks ready to break if the wind blows the wrong way.

By the following day it is twice as thick and tall. Two days after that, it's a fully grown fig tree that overshadows the garden.

But I am shocked on the third day to see Jirobe taking an ax to the tree. We have not spoken since I was forced to kill his impertinent dog. I am still feeling awkward, but not enough to keep my mouth shut. He turns to me angrily when I ask what he is doing. In the end, though, he is too excited not to tell me.

“It's uncanny,” he says. “Last night, I had a dream that Shiro came back to life and dug himself out of the grave. He stood over us as we lay in our futon, his fur covered with dirt and caked blood. In the dream, he could speak. His voice resembled a faraway thunderstorm.

“He said to us, âMy dear father and mother, before I leave you forever, I should give you one more glad tiding. Because of your deep love for each other, your garden is overflowing with bright

ki

that centers on the tree you planted over my grave. If you cut the tree and from it carve a mortar in which to beat rice into

mochi

, the luminous energy shall bring you more riches.'”

Jirobe goes on to explain how he was shocked to learn his wife had had the same dream. They both decided it would be best to do as the dog said. So I look on, perplexed, as my brother chops down the fig tree.

I go over later in the day with some dried fish just as Sakura is steaming glutinous rice for pounding. Her smile fades when she sees me. She pales, as if she is treading on thin ice on a frozen lake. I move my mouth to say something, but guilt is like a plum seed caught in my throat.

The silence lifts only when Jirobe enters, eager to show off his handiwork. He has carved the thick trunk of the fig tree into a mortar big enough to bathe an infant and constructed a large mallet with what remained of the wood.

When the rice is ready, Sakura places it in the mortar. Jirobe swings the mallet down from above his head to hit the cooked grains. Sakura quickly flips the hot white mass over as he pulls the mallet back and readies it for another swing.

Pound, flip. Pound, flip. He says, “Hey!” as he strikes. She shouts, “Ho!” as she flips.

Hey, ho! Hey, ho!

The grains of rice flatten and burst, and before long are indistinguishable from one another.

Flipping over and over, the rice turns into a single slab of

mochi

.

Or at least, it should have turned into

mochi

.

Something instead begins to gleam brightly yellow in the white mass. Jirobe and Sakura's cadence slows and becomes a near whisper. But he keeps hitting the rice.

Why wouldn't he? Wouldn't you keep swinging with all your old man's failing strength, if the more you hit the

mochi

, the more it turned to gold pieces and gems?

When Jirobe finally stops, he and Sakura are giggling hysterically. The mortar is overflowing with treasure. They don't notice that I'm not laughing with them. They've clearly forgotten all about the dried fish I brought.

They become quiet when I demand, more sternly than I intend, that they lend me the mortar and the mallet. They hesitate but, given the usual obligations among family, they have no choice. So Sakura washes the mortar and mallet. I take them home and immediately start to cook rice.

Because my wife is gone, there is no one to flip the

mochi

as I pound it. I make do. I try to turn the rice over myself between swings of the mallet. This proves awkward, and as I tire I do it less and less. The hot grains stick to the sides of the mortar, and soon there's a mess. The more I pound, the more the rice turns into roaches, worms, spiders, caterpillars and something that smells like urine. Frustration and the odor make my eyes water.

I know that this is somehow my father's idea of a sick joke. Somewhere, he is laughing at me. Maybe that cursed dog is laughing at me, too. Maybe Jirobe and Sakura and even my wife are in on the prank.

I'm not laughing. The anger is back, all too familiar. The decision to burn the damned mallet and mortar seems perfectly reasonable.

The insects scatter. The wood resists the hacksaw. Swinging the ax hurts my wrists. Night falls quietly, and by the time the mortar and mallet have been sawed and chopped into small pieces of kindling, the bloated moon sits in the inky sky beyond the window.

I gather the wood, and soon there is a healthy fire in the hearth cut into the floor of the hut. The flames lick the air and beckon me to touch them. The smoke cannot completely hide the stench that still lingers in the air.

I awake the next morning when my brother comes to collect his precious mortar. I no longer care what he thinks of me, and I tell him what I've done. He is no longer concerned with my opinion of him, either, so he sheds his pleasant façade and screams like I've always wished he would. He tells me I'm worthless and only half a man. He tells me our father thought so, too.

I smile stupidly and call him sentimental and pathetic as he collects the ashes from the hearth. He mutters that this is all he has left of the dog and the tree. This is the funniest thing I've ever heard, and I tell him so.