Stories in Stone (11 page)

Authors: David B. Williams

In most subduction zones, if you travel from the ocean to the arc in order you would pass across the accretionary wedge, then

the forearc basin, and finally reach the arc, usually covering a distance of about a hundred miles.

This sequence can be seen

in California traveling from the coastal Franciscan melange and its rich stew of dark sandstones and cherts through the black

shale and tan sandstone of the Central Valley and up into the gray granite of the Sierra Nevada batholith.

Geologists refer

to this zone as the arc-trench gap, the distance from the folded and faulted ocean-derived sediments to the volcanoes, or

the rocks that cooled under them.

“What makes Salinia really interesting is that it screws up that pattern of wedge-forearc-arc” said Dave Barbeau, a geologist

at the University of South Carolina.

29

“We’ve got accretionary wedge rocks, the Franciscan melange, right next to or very close to arc rocks, the Cretaceous granitoids.

Within five kilometers [three miles], some of the forearc rocks are also present.

So the order is wrong and the distances

are really wrong.”

The term “Salinia” refers to an accumulation of rocks that makes up the central coastline of California.

Geologically bounded

on the east and west by the San Andreas and Sur-Nacimiento faults, respectively, and on the south by the Big Pine fault, Salinia

comprises the rocks of the low mountain ranges (Santa Lucia, La Panza, and Gabilan ranges) that run north-south from about

Santa Barbara inland of the coast to Santa Cruz.

The rocks of Salinia include young sediments, older metamorphic rocks, and

medium-age granites, which are Barbeau’s Cretaceous granitoids and include the rocks used by Jeffers.

Salinia has long troubled

geologists, who have called it an “orphan,” because for years no one knew exactly where the rocks originated.

In 2005 Barbeau coauthored a seminal paper addressing the origin of Salinia.

His work was part of a long-term study based

out of the University of Arizona, where he received his Ph.D.

in 2003.

The Arizona team hopes to put together a picture of

plate tectonics in western North America.

Barbeau’s paper focused on two related models to explain the odd juxtaposition of

Salinia and the surrounding rocks.

Model one proposed that Salinia formed between fifteen hundred and thirty-five hundred miles south, in southern Mexico, and

then traveled north and wedged itself into the arc-trench rocks.

Evidence for this long-distance movement came from what is

known as paleomagnetism.

When magma solidifies, iron-rich magnetite crystals within the molten rock align themselves relative

to Earth’s magnetic poles.

By reading these minerals, geologists can determine the rock’s latitude at the time of crystallization.

Barbeau and his co-workers favored a modified version of this model.

Salinia moved north and injected itself into the arc-trench

material, but instead of traveling thousands of miles, Salinia only moved about two hundred miles north, carried along by

the San Andreas fault from around the Mojave desert.

30

Specifically, Barbeau hypothesized that Salinia once filled a gap between the Sierra Nevadas and the Peninsular Range, both

made of granites of similar age and chemistry.

The main line of evidence for the Mojave-Salinia connection came from the mineral

zircon.

“You know there’s the saying that diamonds are forever, but to geologists it’s zircons that are forever,” said Barbeau.

“They

are really resistant to heat and sedimentary processes.

They basically never go away.” The oldest known object on Earth is

a 4.4-billion-year-old zircon crystal, about two human hairs wide, found in rocks from Australia.

Zircon generally forms in

igneous rocks, particularly in granites in sub-duction zones.

When these granites weather and erode, wind, water, and/or ice

redistribute the zircons and they end up in sedimentary rocks.

By analyzing the various zircons in a sediment, geologists

can reconstruct long periods of time, particularly because most sedimentary rocks contain zircons of diverse ages.

“Nearly all of the zircons we see in the Salinian sediments point to a North American origin as opposed to a southern Mexico

one,” said Barbeau.

The zircon grains ranged in age from 80 million to 3 billion years old, with six periods of peak accumulation.

Barbeau’s research indicated that for five of the six peaks the western United States could be the only source of the zircons.

Combined with other data, the zircons showed that after its initial formation Salinia remained in the south for about 40 million

years until the San Andreas propelled the rock on its travels north.

In addition to the overwhelming zircon data, new research has shown that the original interpretation of paleomagnetism erred

in the point of origin for Salinia.

Only a handful of recalcitrant geologists still subscribe to the southern Mexico model.

“This change in perception of how far Salinia has traveled is ideal for understanding the evolution of thought on accreted

terranes,” said Barbeau.

Like the Avalon terrane, which carried the Quincy Granite to the eastern edge of North America, Salinia is also a terrane,

though with some differences.

Avalon is an accreted terrane, meaning that it collided with its new home.

It is also sometimes

referred to as “allochthonous” or “exotic,” which indicates Avalon traveled to reach its present spot.

By definition an accreted

terrane is also an allochthonous or exotic terrane.

A suspect terrane, such as Salinia, is one whose origin is unclear.

The

terms are somewhat fluid and reflect personal choice more than rigid definition.

Geologists first began to focus on terranes after a landmark paper published in

Nature

on November 27, 1980.

In “Cordilleran Suspect Terranes,” Peter Coney, David Jones, and James Monger wrote that 70 percent

of the land from the Rockies to the Pacific Ocean—the Cordillera—was a vast mosaic or collage of landmasses, which the geologists

called “suspect terranes.” More than fifty distinct terranes had collided with North America, including nearly all of Oregon,Washington,

and Alaska, and most of California,Nevada, and Idaho.

The paper did not indicate where the landmasses, which included island

arcs, continental bits, and oceanic crust, originated, but hypothesized that scraps of land littered the Pacific from around

200 to 50 million years ago.

The geologists’ proposed mechanism of transport was eastward movement of the Pacific, Farallon,

and Kula plates, as they progressively sub-ducted North America.

The work of Coney and his partners was critical to the then two-decade-or-so-old theory of plate tectonics.

It showed that

not only did movement of big plates generate geologic features, but also that smaller slivers of land helped form a landscape.

The terrane theory has been called “one of the most significant tectonic concepts” of recent years, particularly as it applies

to the western United States.

31

“When terranes first became popular, they were applied everywhere, probably too much,” said Barbeau.

Whenever someone couldn’t

figure out the exact story for an out-of-place rock it became a terrane.

And the more exotic or suspect the better, which

made the fifteen-hundred-to thirty-five-hundred-mile voyage of Salinia from southern Mexico seem possible.

The “orphan” now

had a parent.

But over the years geologists have honed the terrane concept and learned not to apply it everywhere.

As Barbeau

observed, Salinia is a terrane but it has not traveled far and is neither exotic nor accreted.

“The only reason you have these granite rocks on the coast that Jeffers used for his house is because of this weird tectonic

history,” concluded Barbeau.

“Jeffers’s house is that much more unusual because it’s only that small slice of land between

Carmel and Half Moon Bay where you would find these granitic rocks anywhere along the coast of the western United States.”

To paraphrase Humphrey Bogart in

Casablanca

, of all the rocky knolls on all the West Coast Jeffers chose the one underlain by granite.

And what a difference it made.

Before he started work on Tor House, Jeffers’s poems lacked vitality.

They are imitative, particularly of his early heroes

Wordsworth and Shelley, often focus on love, and have simple, rhyming forms.

But then he moved to Carmel and started his work

with stone.

The metaphors began to take shape.

His education and local influences, his understanding of cosmological and atomic

developments, his daily work with stone, each contributed to his poetry.

“Jeffers always had this timeless, enduring imagery

in his head and just hadn’t found the voice nor the metaphor to make it sing.

So in a sense Jeffers found granite and granite

found Jeffers,” said Aaron Yoshinobu.

Jeffers’s ideas crystallized in Carmel and gave him his distinctive voice.

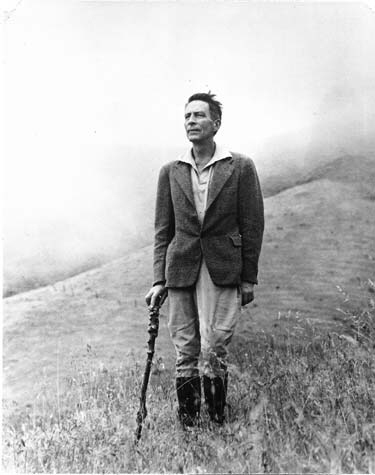

Robinson Jeffers, 1930s.

Once his themes took shape, Jeffers kept working them throughout his life.

Tragedy and suffering, the Big Sur coast, the beauty

of Nature and its redemptive qualities.

The poems are not always easy to read.

His great epic verses, such as

Cawdor

,

Tamar

,

Roan Stallion

, and

Thurso’s Landing

, are filled with incest, brutality, death, and pessimism and stretch for pages and pages, almost more novel than poetry.

As one critic wrote, “Sometimes hard to stomach, they are always difficult to put down.”

32

But many of his poems also contain short and beautiful passages describing his beloved landscape around Carmel.

His devotion to what he calls “my loved subject: Mountain and ocean, rock, water and beasts and trees”

33

is what makes his poetry resonate, particularly his shorter poems.

He writes precisely and knowledgeably about landscape,

both solid and oceanic, and its inhabitants.

Seasonal change plays out in the mountains as they “vibrate from bronze to green/Bronze

to green, year after year.”

34

Gulls are the “slim yachts of the element.”

35

Pelicans flying over Tor House “sculled their worn oars over the courtyard.”

36

Cormorants “slip their long black bodies under the water and hunt like wolves.”

37

Solomon’s seal makes “intense islands of fragrance”

38

and eucalyptuses bend double “all in a row, praying north.”

39

One can learn so much about the natural world from Jeffers’s poetry that it is almost as if he has written a field guide

to the Carmel coast.

But Jeffers’s use of geology and geologic metaphors shines above all else.

Weathering is “the endless ocean throwing his skirmish-lines

against granite .

.

.

/ that fierce music has gone on for a thousand/Millions of years.”

40

In an homage to evolution and geologic time, he wrote that “the wings torn with old storms remember / The cone that the oldest

redwood dropped from, the tilting of continents, / The dinosaur’s day.”

41

During erosion “Cataracts of rock / Rain down the mountain from cliff to cliff and torment the stream-bed.”

42

In contrast a resilient stone is “Earthquake-proved, and signatured / By ages of storms.”

43

Jeffers clearly paid attention to the natural world around him.

Ever since his childhood he had had a connection to nature,

but not until he settled in Carmel and worked on the land did he develop the knowledge and strength that gave him that passion

to describe place.

And this relationship centered on the house and tower he built from granite boulders on a low, barren knoll

overlooking the sea.

“The place was maiden, no previous / Building, no neighbors, nothing but the elements, Rock, wind and sea,” wrote Jeffers

in a poem titled “The Last Conservative.”

44

Tor House and Hawk Tower are the only structures he could have built for the site.

How could I not love those buildings?

In his ode to Tor House, Jeffers concluded, “My ghost you needn’t look for; it is probably / Here, but a dark one, deep in

the granite.”

45