Stories for Boys: A Memoir (26 page)

Read Stories for Boys: A Memoir Online

Authors: Gregory Martin

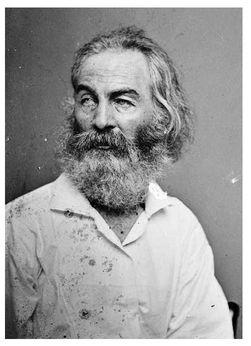

Sometime past midnight, I sat up in bed. The room was in shadow. A number of questions came to me in rapid succession. Why couldn’t Evan hug his teammates if he wanted to? Why was I so embarrassed? What was that all about? Was it really because he was interrupting practice? Distracting the other players? Why so angry? Disappointed? Was my disappointment really about his attention span? Did it really have anything to do with sports? A hug from a six-year-old was a hug. It was affection and happiness and innocence. It was beautiful. I was the ugly one with the scowl on my face. Where was my sense of humor? Where was my joy in my son’s easy authenticity? Why was I disappointed that my son didn’t want to be the most dominant six-year-old boy on the field? What the fuck was wrong with me? What would Walt Whitman say? He would sound his barbaric yawp right in my face.

I got up and went into the kitchen and opened Christine’s stainless steel refrigerator. A swath of light streamed into the dark. I poured myself a glass of milk. Why did it seem that my epiphanic, revelatory thoughts on this matter were not particularly new or profound? Why was I so stupid? Hadn’t I learned anything?

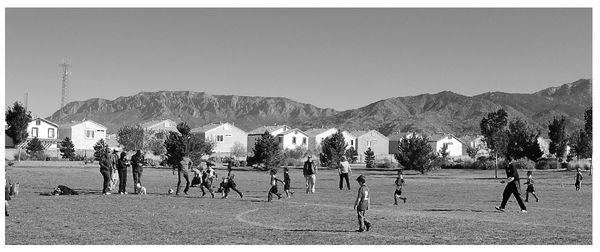

ALL SEASON LONG, I’d told Evan, that if he kicked the ball five times in a game, I’d take him out for ice cream. He’d never earned ice cream. Late in the first half of the last game of the fall season, the ball rolled right at him. He noticed it. He didn’t have to move anything but the muscles in his lower right leg. He moved them. He made contact, small black cleat on ball. He kicked the ball with his toe, not his instep or laces, but still. The ball rolled away from Evan in the wrong direction, toward the other team’s goal. Evan was ecstatic. I was on the field, refereeing. I saw it all.

Evan abandoned the ball, ran toward me and shouted, “Dad! I kicked it! That’s one!”

“Awesome,” I whispered neutrally. “Kick it again.” I felt guilty that this longstanding bribe was suddenly working, especially after my late-night epiphany. I didn’t want Evan to play soccer just to please me. But I was pleased, despite myself. Soccer was such a great game. I’d thought all along that if he just got into it, he might start to like it for its own sake.

In the second half, a boy on Evan’s team took a well-kicked ball in the stomach and had the wind knocked out of him. I blew the whistle, stopped play and had everyone take a knee. The boy moaned but didn’t cry. He stood up quickly but was still doubled over. He was trying to shake it off. He didn’t look over to the sidelines. The last thing this boy wanted was what he really wanted: a hug from his mom or dad. I put my hand on his shoulder. I asked him if he wanted to take a break for a while. He could come back in whenever he was ready. He winced. He shook his head. He didn’t want to go out. I told him to tell me when he was ready. He took a few breaths and stood up straight. He was ready.

The re-start in this situation is a drop ball. Two players face off and the referee drops the ball between them and when it hits the ground, the ball is live. There had been a number of drop ball re-starts. The usual suspects volunteered, raising their hands highly. Evan didn’t raise his hand, but I chose him anyway. Then I chose the one boy on the other team who was a butterfly chaser like Evan. They faced each other. I held the ball between them.

“Now when the ball hits the ground, you guys kick it, okay?”

They nodded.

I dropped the ball. Evan got to it first and kicked it hard. The ball ricocheted off the other boy’s shin guard and came back to Evan. He kicked the ball again. It ricocheted back. Evan kicked it again and the ball rolled clear.

“Dad!” Evan screamed. “That makes four!”

“I know,” I said out of the side of my mouth. “Go get one more.”

Six-year-olds in Evan’s league play twenty minute halves. With four minutes left in the second half, it didn’t look like Evan was going to get his fifth kick. He wasn’t watching the ball but walking around in loose circles near the middle of the field. After the last game, which his team had lost twelve to three, Evan asked me, “Did we win?”

The ball rolled toward Evan. Something registered in his peripheral vision. He looked up. There wasn’t enough time for conscious thought. It would have to be all reflex. Evan’s primal instincts kicked the ball. The ball went rolling forward, in the right direction. There was no one between the ball and the goal. But the goal was a long way off and Evan hadn’t kicked it that hard. He would have to run after it and kick it again to score. He would probably have to kick it a few times.

Evan turned and ran away from the ball, toward me. “That’s five!” He did an ice cream dance.

A boy on the other team reached Evan’s ball, turned it skillfully, and took off dribbling in the other direction.

I ran along near the play. Evan ran beside me. He tugged on my black and white jersey. “Dad,” he said, as if I had failed to understand the significance of what had happened. “That’s five. Ice cream. Remember?”

“Yes, son. I remember. Great job.” I stopped and put my hand out and we high-fived, but I felt awful inside, a terrible sinking feeling. Then I ran across the field towards the ball.

Evan veered off, settled into a stroll. He returned to circling the center of the field. Boys ran back and forth, chasing and kicking the ball.

After the game Evan ran happily through the tunnel made by all the parents’ upraised, connecting hands. This is Evan’s favorite part of the game. He sat on the grass with the other boys and savored his post-game Rice Krispie bar. He drank his juice box. He told everyone – his teammates, their parents – about his ice cream plans and how this reward had come about. There was envy and begging. One teammate mentioned sweetly to his parents that he had kicked the ball a lot more than five times. Another teammate seconded this general estimation to his parents. These parents shook their heads. They kept their thoughts to themselves. Evan was oblivious. He had met the challenge. His work here was done.

Fractions and Story Problems

CRISTINE CAME HOME FROM GROCERY SHOPPING, AND I went out to help her bring in the bags. I said, “I want to tell them. I want to tell them right now.”

It was the middle of a Sunday afternoon.

Christine said, “No. I don’t think you should.”

“I want to.”

“They’re hungry. It’s not a good time.”

I said, “There is no good time.”

What I didn’t say, but what I know now, is that I hated that Oliver knew only part of the truth about my father. The wrong part – the part we did not want him to know. His Grandpa had attempted suicide. Sadness over the divorce was only part of the reason. But Oliver didn’t know why they divorced. He didn’t know his grandfather was gay. I thought about him trying to sort this out in his mind. I thought about how it could not possibly have made any sense.

So Oliver knew a fraction of what happened and a fraction of the reason, and Evan knew nothing. This galled me, gnawed at my conscience. I’d been thinking about it more and more. My childhood had been one layer of silence and secrets over another. So had my father’s. I did not want to pass on this inheritance to my sons. I wanted them to know the truth, as much as they could handle, as much as they were ready for – though I didn’t know how much that was. I wanted them to understand my sadness. I did not want to be a mystery to my sons – or no more, anyway, than I already was, and always would be.

Christine stood there in the driveway, a gallon jug of milk in each hand.

“I’m telling them,” I said.

Christine walked past me, went through the front door and into the kitchen and started putting away groceries. Her jaw was set. She would not make eye contact. We put away all the groceries. She said, “We need to talk to Oliver first.”

Oliver was reading a book on the couch. Evan was in the back yard. We asked Oliver if we could talk to him back in the guest bedroom, on the futon. He looked up immediately and said, “Am I in trouble?”

We shook our heads and told him no, at the same time. Oliver said, “I’m definitely in trouble.”

We all went back to the futon and sat down.

Christine took Oliver’s hands, and said, “Remember that story you read that Daddy wrote, about Grandpa? It was in the magazine next to our bed.”

Oliver nodded his head. “When he took all that medicine.”

I said, “We’re going to tell you more about that story now, but we want to make sure you don’t tell Evan about Grandpa taking too much medicine. He’s not old enough to know that.”

“Suicide,” Oliver said.

“He’s not old enough to know about that,” I said again.

Oliver nodded. “I know.”

Christine said, “But we want you to know that you can talk to us about it, if you want. Anytime. We didn’t tell you that well enough last time.”

Christine waited. Oliver didn’t say anything.

I went out to the back yard to get Evan. He was swinging in the hammock that Christine had strung under the treehouse. He was singing to himself. At the time, I didn’t think, “He’s so happy. This isn’t the right time. He’s too little.” Evan rolled out of the hammock and came running when I called his name and told him we were having a family meeting back on the futon. He ran through our small house and back into the guest bedroom and jumped on Oliver and they started wrestling. Christine and I both pulled them apart, untangling arms and legs. Christine sat between them and tried to keep them apart. Evan lunged for Oliver again.

I pulled up a chair and sat opposite them and said, “We have something to tell you both about why Granny and Grandpa got divorced.”

Evan stopped reaching for Oliver. He looked up at me. The play went out of his face.

I didn’t know what I was going to say. Even though I’d been thinking for more than two years about what I might say to them someday about this, I hadn’t rehearsed anything. I just started talking.

“Granny and Grandpa divorced because Grandpa is gay. But Granny didn’t know this about him for years and years because Grandpa kept it a secret. When they got married, forty years ago, she didn’t know he was gay. She didn’t know when I was growing up, either. Grandpa kept it a secret from her because he grew up in a time when it wasn’t okay to be gay. He grew up in a time when you could get beaten up or even killed if you were gay, especially where he lived, in the South. Remember how we talked about the Ku Klux Klan. Well, Grandpa grew up in a time and a place where there were people like the Ku Klux Klan who hated people who were gay and would hurt them terribly.”

Oliver said, “The Ku Klux Klan isn’t gone. There are still people in the Ku Klux Klan, and they still believe those things.”

Christine said, “That’s right, Oliver.”

Evan shouted, “Grandpa is

gay

?” He started to cry. He jumped off the couch and started running around the room, waving his arms in the air. He shouted, “Too sad. Too sad. I don’t want to hear anymore.” He ran out of the room.

gay

?” He started to cry. He jumped off the couch and started running around the room, waving his arms in the air. He shouted, “Too sad. Too sad. I don’t want to hear anymore.” He ran out of the room.

Before Christine and I could go after him, he ran back in and I pulled him on to my lap. He shouted, “Does that mean I’m gay? Does that mean I’m a quarter gay?”

“No son, that – ”

“But you’re

half

gay, Dad!” Evan shouted.

half

gay, Dad!” Evan shouted.

“No, it doesn’t – ”

“I hate Grandpa. Papa is my favorite now.” Evan’s thin little chest was heaving.

Other books

Detroit: An American Autopsy by Leduff, Charlie

Hardcase by Short, Luke;

Mr Lincoln's Army by Bruce Catton

Hoping for Love by Marie Force

The Ordways by William Humphrey

Prince of Demons 3: The Order of the Black Swan by Victoria Danann

Gift-Wrapped Governess by Sophia James

The Duke and The Duchess by Lady Aingealicia

The Dragon in the Ghetto Caper by E.L. Konigsburg