Stories for Boys: A Memoir (12 page)

Read Stories for Boys: A Memoir Online

Authors: Gregory Martin

“So, basically, your typical RV park,” I said.

My father laughed. Then his tone changed completely. “It was the way it should be.”

“Amen,” I said.

Neither of us said anything for a few moments. I thanked him for his thoughts on the book I’d given him. I asked him when he thought he was going to move into the condo. He was still waiting for the bank approval.

“Where did you find this place?”

“The condo or the campground?”

“The campground.”

“On the internet,” he said.

“That’s great,” I said. “I’m happy for you, Dad.” And I was, sort of.

To Catch a Thief

MY MOTHER CALLED ME. SHE DIDN’T SAY HELLO. SHE said, “I’ve changed the locks.”

“Why?”

“Your father was in the house.”

“He didn’t ask to come over?”

“No.”

“ What did he want?” I knew that my father still had several boxes of things, and some unboxable things, like golf clubs, skis, and his bicycle, in the basement and the garage. My mother wanted him to come and get all this stuff, but so far he hadn’t called to arrange a time. My mother didn’t want to be there when he picked it all up. It was September. It had been four months since he’d moved out. More than once, my mother had said to me: “If he doesn’t come soon, it’s all going to be out on the curb with a ‘free’ sign.” My father, it seemed to me, was using his golf clubs, skis, and bicycle to punish my mother for exiling him for a lifetime of betrayal. Classic, post-divorce, bush-league, passive-aggressive antagonism. I didn’t want to get in the middle of it. I didn’t want to pick sides, even though picking sides wasn’t difficult.

My mother said, “He wanted some paperwork in the office, in the filing cabinet. He’s moving. He’s buying a condo.”

“Did he apologize?”

“Words, words, words.”

“He didn’t get those boxes?”

“He did not.”

“I’m sorry, Mom.”

“This is not his house anymore. He cannot come and go.”

“I know.”

“Why would he do that? Why would he want to hurt me more?” she said. “Why wouldn’t he ask?”

“ I don’t know.”

“I don’t know him.”

“I know.”

When I got off the phone with my mother, I did not call my father. I did not think,

Robert has recommended anger. Here is another perfect opportunity

. I thought,

Hasn’t he hurt her enough?

Robert has recommended anger. Here is another perfect opportunity

. I thought,

Hasn’t he hurt her enough?

A WEEK LATER, my mother called me. She did not say hello. She said, “Your father stole from me.”

“No.”

“Yes.”

“He withdrew three hundred dollars from my bank account.” My mother’s voice was shaking. I could see her face in my imagination. She was baring her teeth.

“He would never do something like that,” I said. What I wanted to say, but didn’t, was that my father was the most honest man I knew.

“You don’t know him,” my mother said.

I CALLED MY father. He picked up. I shouted, “Why did you steal from Mom? You can do whatever you want with your life now, but you cannot hurt her anymore.”

“Don’t get in the middle of this, son. You don’t know – ”

“You stole from her,” I shouted again.

“I did not steal,” my father shouted back. “I took without asking. There’s a difference.”

I laughed – a derisive, scornful laugh. “That’s called stealing.”

“No.”

“Yes.”

I was out on the back patio. The boys gathered at the door. They were leaning into the glass, watching me, like at the aquarium. Christine tried to steer them to other exhibits, but they kept squirming free, running back. I was the best exhibit going. It was just after dinner, an hour or so before dark.

Christine opened the patio door and said, “We’re going to the park.”

I nodded.

The boys shouted as they were dragged away, “What’s the matter? Why is Daddy so angry?”

I told my father that I didn’t want to hear his “side of the story.” There was no other side of the story. There was only one story, and I understood it well enough. My father did not have enough money in his account to cover the closing costs on his condo. There was a deadline. He went online, entered the user name and password for my mother’s account, and he transferred money from her account to his.

My father said that he had

borrowed

the money. He had every intention of paying it back.

borrowed

the money. He had every intention of paying it back.

“You stole,” I said. “Mom has changed the fucking locks. Why? Because you went into her house without asking, when she wasn’t there. That’s called

breaking and entering

. What the fuck are you doing? What is she going to have to do next? Get a restraining order?”

breaking and entering

. What the fuck are you doing? What is she going to have to do next? Get a restraining order?”

My father didn’t say anything.

“I don’t care what your reasons are. I don’t want to hear your story. I only care about what you did.”

Ten, twenty seconds passed in silence. My father said slowly and clearly, “I don’t ever want to speak with you again. I want you completely out of my life.” Then he hung up.

I stared at the phone in my hand. I walked around the back patio, my heart pounding, adrenaline coursing through my blood. Mourning doves were calling out from the phone wires above our back fence. The wind was blowing in the trees. The sun was low and red in the Western sky.

My father called back. I let the phone ring. He didn’t leave a message.

E-blame

OVER THE NEXT SEVERAL DAYS, MY FATHER AND I LASHED out at each other in a series of long, painful to re-read, recriminating emails:

Me:

When you ask for money from someone, and you are given that money, this is borrowing. When you do not ask for money from someone, but take the money without the other person knowing, this is stealing. Oliver knows this, and he is seven. You and mom taught this to me a very long time ago, and you were both right to do so. There is nothing blurry about this boundary.

My father:

I am incredibly sorry that you are so deeply troubled by the revelation that I am gay and have been for most of my life.

Greg, it seems to me that if we are to have a continuing relationship, you are going to have to stop making demands of me that I cannot meet in this lifetime. I am working on healing what remains of my life and you are not helping. If anything, so far, it appears that you are looking for a reason to write me out of your life because I make you too uncomfortable.

Me:

Your sexual orientation is not what is keeping us apart. So please don’t try to oversimplify my reaction by claiming that my problem is that you’re gay. It’s not. My problem is that you hurt mom again. You made a bad judgment; you also entered her house without her permission, which was also a bad judgment. This hurt her also. When you stop doing things that hurt mom, and when you start seeing that this is the problem, then we’ll have clear ground to speak to each other from.

…for you to say that you were justified in being as angry as you were strikes me as coming from a place of deep denial, and an unwillingness to see yourself, and your choices, as the source for this latest round of heartache. And so I just don’t find much sympathy in my heart for your denial. I’m weary of your denial and of your refusal to take accountability for your actions. I see you trying to lash out at me rather than look long and hard and humbly at the bad choices you made.

Your ability to justify bad choices must be very powerful – how else could you have kept up such a deceitful life for so very long?

My father:

I am sincerely sorry that I cannot live up to your expectations. If you recall, I’ve never had the patience to argue with you. I still don’t. I’m finished with this line of attacking me. Please write me back when you can move on.

Whitman

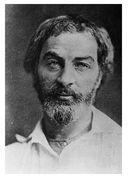

IT WAS SATURDAY AFTERNOON IN OCTOBER. I WAS IN front of the television. Outside, it was a bright sunny day, the kind of day that makes people want to live in New Mexico. The kind of day to take your boys to the park. I was watching a PBS documentary on Walt Whitman.

I am to see to it that I do not lose you

I am faithful

I do not give out

Through me forbidden voices,

Voices of sexes and lusts, voices veil’d and I remove the veil,

Voices indecent by me clarified and transfigur’d

CHRISTINE AND THE boys came home from the park. I wasn’t the mayor anymore. I had resigned, but without any speech or fanfare. My administration’s accomplishments would have to speak for themselves.

Oliver joined me on the futon and watched some of the documentary with me. They had just started talking about Whitman’s volunteering as a nurse for the Union during the Civil War. For three years, he lived in a boarding house in D.C. and went to be with the young soldiers for seven or eight hours each day. Sometimes he spent the night sitting in a chair beside them so they would not die alone. Oliver was immediately taken in, fascinated by the black and white grainy photographs of the slain and wounded soldiers, photos of amputated limbs, the burial teams at work, the field hospitals, the surgeons, their rolled-up sleeves and blood-soaked shirts. Whitman wrote in his notebook:

I do not see that I do much good to these wounded and dying, but I cannot leave them… Most of these sick or hurt are entirely without friend or acquaintances here.

I started to cry. Snot poured out my nose. My mouth was open but no sound was coming out. Oliver left the room and came back with Christine, who sat down beside me and rubbed my back and held me. Oliver was confused. He looked scared. He asked why I was so sad, and when I could finally catch my breath to answer, I said something about how horrible war could be, which was a small part of the truth.

A Well-Made Man

BORN IN 1819, ONE HUNDRED AND TWENTY-TWO years before my father, Walt Whitman became the person he was and invented the person he became. He cultivated idleness and leisure. He loafed and invited his soul. He sang the body electric.

The armies of those I love engirth me, and I engirth them;They will not let me off till I go with them, respond to them;And discorrupt them, and charge them with the full charge of the Soul. […]The expression of the face balks account;But the expression of a well-made man appears not only in his face;It is in his limbs and joints also, it is curiously in the joints of his hips and wrists;It is in his walk, the carriage of his neck, the flex of his waist and knees—dress does not hide him;The strong, sweet, supple quality he has, strikes through the cotton and flannel;To see him pass conveys as much as the best poem, perhaps more;You linger to see his back, and the back of his neck and shoulder-side.

It’s a good thing people were so open and affirming in 1855, the year Whitman self-published the first edition of

Leaves of Grass

. Well, everybody except the most prestigious literary critics of the day. Here are a few excerpts:

Leaves of Grass

. Well, everybody except the most prestigious literary critics of the day. Here are a few excerpts:

his punctuation is as loose as his morality

a mass of stupid filth

natural imbecility

slimy work

vile

intensely vulgar

absolutely beastly

an escaped lunatic raving in pitiable delirium

an explosion in a sewer

Other books

Winter's Warrior: Mark of the Monarch (Winter's Saga 4) by Luellen, Karen

The Famous and the Dead by T. Jefferson Parker

On the Grind (2009) by Cannell, Stephen - Scully 08

Demon's Bride by Zoe Archer

The Very Thought of You by Rosie Alison

Coming Home by Shirlee Busbee

The Girls She Left Behind by Sarah Graves

Fast Company by Rich Wallace

Shared by the Highlanders by Ashe Barker

Secret Combinations by Gordon Cope