Still Foolin' 'Em (21 page)

Authors: Billy Crystal

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Entertainment & Performing Arts

After we’d shot for five weeks in Durango, Jack joined us for two weeks of shooting in New Mexico. We were a well-oiled machine by the time “the Big Cat,” as we called him, arrived. The crew was as excited as I was about his arrival. When Jack, dressed all in black, arrived on the set, everyone applauded. Jack’s first shot was to confront a ranch hand who was making lewd remarks to Helen Slater’s character. He would rope the dude around the neck and then enter the corral and confront him and me, which would start our relationship. Ron, who is a gentle, sweet man, easily mistaken for a puppeteer, softly explained to Jack what he wanted: “Then you come through the gate and see Billy and give him a glare—”

Jack pounced: “What the fuck does that mean, give him a

glare

? I don’t glare, I’m a fucking actor—tell me what I’m thinking, not what I’m doing!” He then took off his hat and threw it and a shit fit. The crew, just moments ago so excited, was now confused and pissed off. Things had been going swimmingly, and now “the Big Cat” apparently had a thorn in his paw and was attacking Ron, whom they really liked. I quieted Jack down, and Ron apologized to Jack as best he could.

I did this in my first life also.

“Let’s just fucking do this!” Jack yelled.

“ACTION!” Jack got off his horse, walked through the gate, and gave me a

glare

like a laser beam that went through my head and burned a hole in the fence behind me. “CUT, PRINT!” said Ron. It was a lesson to us all. Jack knew what he was doing, he knew who he was, and he needed to be talked to in a certain way. After that day, Jack and I were alone for ten days shooting all of our scenes together, including the one where we birth Norman, our little calf. That scene is one of the most talked about in the film. I’m asked all the time what it was like to birth a calf, because it looked so real. Our special effects crew created the rear section of a cow. (Apparently one of them was once a plastic surgeon in Los Angeles.) It was a perfect anatomical replica, complete with “lungs” that would breathe as a cow in distress would. They covered a few-days-old runt calf in realistic bloody jelly and folded the little guy up, and I pulled him out of the faux birth canal. He must have been thinking,

Didn’t I just get out of here?

It was a lovely moment between Jack and me.

For a crusty, sometimes intimidating man, Jack was actually a very sensitive guy. He understood how to act on film better than anyone I had worked with up to that point. He knew how to hold the frame. More than anything, he knew that the size of his head was a powerful instrument. All great movie stars have big heads. Chaplin: big head; Spencer Tracy: big head; Gable: huge head; Meryl Streep: all head; Bogart: big head; Katharine Hepburn, Cagney—the list goes on and on. Jack found the right way to hold his big head, and Dean Semler understood exactly how to light him. He also was a poignant figure to me. Curly was meant to be the last of the cowboys, and Jack, at this stage of his life and career, embodied that idea of a dying breed. He had trouble remembering his lines at times. I would watch him rehearsing his words with his wife, and I would walk over and say I was having trouble with the scene and would he mind going over it with me. He labored some days to get his seventy-year-old body onto his horse for all the hours we had to be in the saddle. He never complained. On the night we finished shooting Jack’s work in the film, I had a quiet moment with him, and I told him what an honor it was to work with him. Then I asked, “Why did you go so crazy that day? Why did you yell at Ron like that and carry on?”

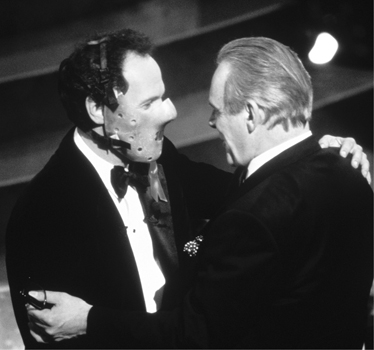

With Jack Palance in his last shot in the filming.

He looked at me and simply said in that gravelly voice, “It was my first day. I always get nervous on the first day.”

“How many movies have you made?” I asked.

“Counting the shit I did in Europe?… About three hundred.”

“And you still get nervous?” I asked incredulously.

“Only on the first day,” he replied.

We said our good-byes, and a few weeks later we finished shooting the film. Once it was cut, we had our first test screening, and it went through the roof, as they say. Other screenings went even better, and when it was finally finished, we were invited to take it to the Cannes Film Festival. We weren’t in competition; we were there to show it to foreign exhibitors for the European sale. Castle Rock threw a big party for the film and to honor Jack, who was an icon in Europe. We were booked at the Hôtel du Cap, one of the truly great hotels in Antibes, where everyone stays during the festival. Fresh from our party, Jack and I walked in together, and as the paparazzi’s flashbulbs were blinding us both, through the blue dots in my eyes, I spied Charles Bronson sitting on a couch with Sean Penn. Bronson and I made eye contact, and I nodded slightly toward him (though I wanted to say “Fuck who?”), and he quietly got up and left.

City Slickers

was Castle Rock’s first movie and helped put the production company on the map, and to have gotten to make the film with my friends meant everything to me. Finally people stopped asking me if they looked mahvelous and started asking me what the “one thing” was, and how was Norman the calf? The Golden Globes honored us with several nominations, including Best Comedy, Best Supporting Actor for Jack, and Best Actor in a Comedy for me. We were sitting together when Jack won. I was elated—this meant he had a real shot at the Oscar. He made a short speech and came back to the table.

“Jack, you’re supposed to go to the press room,” I told him.

“No way—I’m gonna be here when you win.”

I was very moved, but then shortly thereafter I lost. Instantly, Jack got up to leave. “Where are you going?” I asked him.

“The press room—you lost.”

* * *

Next came the Oscars—one of the best nights I ever had as an entertainer, even though I was suffering from pneumonia. A fever of 103 degrees, cough, stuffed-up ears and nose—you name it. I was exhausted. Gil Cates was so concerned about me that he had talked about having Tom Hanks stand by in case I couldn’t do it. Janice’s chicken soup helped some, but I had no energy, and the powerful meds I was on sapped my strength further. I made my entrance being wheeled out by some medical personnel, strapped to a gurney wearing the Hannibal Lecter mask that nominee Anthony Hopkins wore in

The Silence of the Lambs.

I walked right off the stage and greeted him in the audience, saying, “I’m having some members of the academy for dinner—care to join me?”

Oscars opening with Anthony Hopkins—love at first bite.

During the show, from the stage I could see Jack’s big head above everyone else’s. In my gut I knew he would win, and of course he did. I was in the wings when he was named the winner, and I wanted to run across the stage to him, but I just watched as he uttered, “Billy Crystal, I crap bigger than you,” which was a line from the movie that no one remembered at the time. Many thought he had dissed me. He then, of course, hit the deck and did a few one-armed push-ups, and the place went wild. Bruce Vilanch and Robert Wuhl were in the wings with me. We huddled during the commercial break and I said, “Let’s run with this,” and we did. “Jack Palance just bungee jumped off the Hollywood sign,” I said, and, later, “Jack won the New York State primary.” There was a musical number with thirty children in it: “Jack is the father of all of these children.” It was just perfect.

Later in the show, I introduced Hal Roach, one of the great pioneers of movie comedy. Hal was the creator of

The Little Rascals

and had teamed Laurel with Hardy and was that night one hundred years old. After my intro, he was simply to stand up in the audience and wave to the crowd. Well, he stood up and started talking, but he wasn’t wearing a mike, and no one could hear his frail voice. He kept going on and on, and it became a little awkward. I was at center stage as they tried to get a mike to him, to no avail. My mind was racing with lines, and I knew the Cyclops was looking at me with its red light, letting me know that a billion people were watching me smile patiently at Mr. Roach and hope I could salvage the awkward moment. Suddenly, a line settled in my head, like the three cherries in a slot machine. “It’s only fitting,” I said. “He got his start in silent films.”

The crowd roared, the moment was saved, and for me, it was a time that I can say I was a good comedian. Later in the show, my fever spiked and I got very woozy. As I tried to introduce Liza Minnelli, nothing came out of my mouth right, and I just stopped and said sarcastically, “Didn’t inhale,” a reference to Bill Clinton, who had recently claimed he had smoked pot but hadn’t inhaled. The crowd laughed, but I felt seriously unwell. During a break they rushed me into Gil’s production office to get some fluids into me. Paul Newman was there, preparing for his appearance. He took a look at me and said, “You look like shit, but you’re having a great show.” I lay down, and a paramedic gave me fluids as Paul put a pillow under my head.

“Great to meet you,” I remember saying. I finished the show feeling better and went to the Governors Ball. People were very kind to me as Janice and I made our way into the celebration. Jack was standing at a bar with his lovely wife. He didn’t embrace me, he didn’t shake my hand; he simply put his hand, the one holding the Oscar, on my shoulder, stared at me for a moment, and said, “Billy Crystal … who thought it would be you?” I’ve thought about that line all these years. Of all the great parts he had, and all his fine performances, his career in Europe making countless B movies and then doing silly television shows like

Ripley’s Believe It or Not!,

he finally, at age seventy-three, gets an Oscar for doing two weeks in a movie opposite a comedian and a calf. From seeing him in

Shane,

to being him when we were writing the script, to acting with him and finally having that craggy big-headed icon getting what he deserved, I felt like some sort of Rubik’s Cube had been completed. We had a glass of champagne together, and I could only imagine what Charles Bronson was thinking as he went to sleep that night.

* * *

Mr. Saturday Night

was the first picture I directed, and it was a backbreaker. Coming off

Throw Momma, Midnight Train, When Harry Met Sally

…,

City Slickers,

and the successful Oscar shows may not have been the right time to play a bitter seventy-three-year-old comedian, no matter how funny he was. I first did Buddy Young Jr. in the HBO special

A Comic’s Line,

without any kind of special makeup to age me. Then at

SNL,

in a film piece, we made me look older, and the character became an insult comic doing a cheesy one-man show. I also did him on “Weekend Update,” where he was a restaurant critic who would leave the desk and work the live crowd. One night Christopher Reeve, Waylon Jennings, and Johnny Cash were in the audience, and I went after them like Rickles would: “Waylon, nice hat—when did you go Hasid?” Still, I felt there was something more to Buddy, and when I did my

Don’t Get Me Started

special for HBO, I knew how to go after that. The makeup design was great; it aged Buddy naturally. And I created a “life” for him. His family, his wife, his career. It gave him the sort of natural poignancy I often felt when I was around older comics. He was now a real guy rooted in the world of borscht belt comedians, like Alan King and Gene Baylos. I was very comfortable playing older characters. Maybe I was getting ready for this book.