Starvation Lake (45 page)

Authors: Bryan Gruley

Tags: #Journalists, #Mystery & Detective, #Michigan, #Crime, #Fiction, #Suspense, #Mystery fiction, #General

“By the way,” Joanie said. “I was trying to tell you something when we got cut off the other day. I noticed something in my Bigfoot notes I missed before. Dufresne chaired some little state committee that gave Perlmutter a bunch of the money he used for his Sasquatch stuff.”

I was staring at Dufresne’s signature. There was something strangely familiar about it. I grabbed the envelope off the sink and looked again at Francis’s handwritten note.

“Joanie,” I said. “Did you write that bank story?”

“What does that have to do with anything?” Mom said.

“Why?” Joanie said.

“Did you?”

“Yeah. Six inches.”

“Which bank bought which?”

“Why?”

“Which, please?”

“Chill out. City-something from New York bought First Detroit. So what?”

“And First Detroit owned what or used to own what? Didn’t Kerasopoulos have a buddy who’s a big shot at one of the banks that got bought?”

“Yeah. It’s just called First Detroit now, but it used to be called—”

“First Fisherman’s Bank of Charlevoix.”

“Yeah. So?”

I had to clutch at the slab to keep from doubling over. The paper fluttered to the floor. “Gus,” Mom said. “You’re pale.”

The cell door creaked open. “Time’s up,” Darlene said.

My mother swung around. “Darlene Bontrager,” she said, using her maiden name.

“Two minutes,” Darlene said.

Mom got up and sat down next to me and put an arm around me.

“Gussy,” she said. “What is it?”

“Why didn’t you tell me these things? I asked you about Leo. Why didn’t you tell me about Dad and his job and his movie projector and his investment?”

“Do you really want to know?”

“Yes. I do.”

“All right.” She gave me a look I hadn’t seen since the day she told me Dad was gone. “It’s simple, actually. You really didn’t need to know, but even if you did—even when you were asking me—you weren’t ready to know. You were too young.”

“Too young at thirty-four?”

“Thirty-four, twenty-five, fourteen. What difference does it make? You boys, you and Soupy and the all the rest, you got out of high school and you had your chance to grow up but you chose to stay boys forever, playing your little games as if they really matter.”

I fixed my eyes on the floor. “I know they don’t matter, Mother.”

“No, you don’t. You’re still acting like a boy. Running here and there instead of settling down and facing the facts of your life. You left this place, a place you loved, because of a stupid little mistake you made in a stupid little game. Instead of the people you loved”—she didn’t have to look back at Darlene—“you put your trust in silly prizes and sillier superstitions, in, in, I’m sorry, whatever that foolish glove is you wear, as if those things could somehow make you more than what you are.” She put the tissues back in her pocket. “I love you, son. But I was afraid that telling you what I knew would only drive you farther away. You were already far enough away for me.”

I let her words sit there for a minute.

“Thanks a lot,” I said.

“I’m sorry.”

“Why did you come here?”

“I came here for you.”

“Give me a fucking break.”

“Gus,” Joanie said.

“It was

my

fault that you kept secrets? Bullshit. I’ll bet you still know more than Joanie’s been able to wheedle out of you. And you’ve known it for years and years but old Spardell told you not to talk so you didn’t talk, not even to your own son. Was that the right thing to do? Just keep your mouth shut and keep cashing the checks? Why don’t you go see Francis? He paid your damn taxes.”

Joanie stood and reached for my mother. “That’s enough,” she said.

My nerves felt as if they might poke through my skin. What could I tell them that would make them all happy? What did I really know that they didn’t know already? Nothing had changed since Dingus marched me into that cell. Except, perhaps, this thing about Dufresne. I couldn’t get that signature—Francis J. Dufresne—out of my mind.

“You’re wasting your time,” I said. “Sorry.”

“Stop being sorry,” Mom said. “Everyone is sick of it.”

Darlene held the door for Mom. Joanie stayed.

“Remember that priest at my high school?” she said.

“What priest? What about him?”

“Here.” She pulled a piece of paper from her jacket pocket and set it on her chair. “Not that any of this matters anymore,” she said.

“What the hell are you talking about?” I said, but Darlene took Joanie by the sleeve and ushered her and Mom away.

I lay back on the slab and closed my eyes, but I couldn’t sleep. Soon Joanie and Tawny Jane would be opening those FedEx deliveries. I wondered if Tawny Jane would come to the jail looking to interview me. Maybe I’d be gone to Detroit by then.

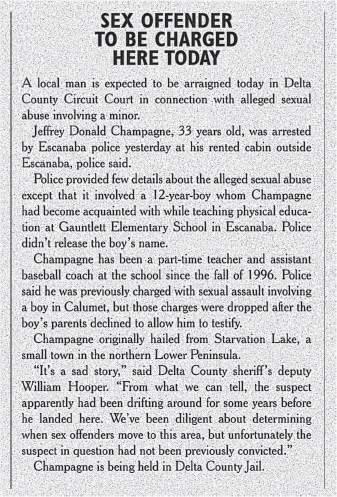

I sat up and grabbed the paper Joanie had left. It was a photocopy of a story that had run in the

Daily Press

of Escanaba, Michigan, three months earlier:

“No way,” I said.

“What?” Darlene said. She was still standing outside.

“Nothing.”

I understood that the suspect was the very same Jeff Champagne who had played for the River Rats. I did not want to believe that the cop was Billy Hooper. There had to be a lot of William Hoopers in Michigan.

Darlene opened the cell door and stepped inside. “Come on, Gus,” she said. “You don’t really want to go back to Detroit.”

“Call off the state boys.”

“It’s not up to us, it’s up to you.”

“I’ve done what I can. You’ll see. What time is it anyway?”

She looked at her watch. “Time to go.”

“Go where?”

“Leo’s funeral.”

“Right. Tell everyone I said hello. And to watch for the

Pilot

tomorrow.”

“You can tell them yourself. Let’s go.”

She was serious.

“Come on, we’re going to be late.”

“Dingus said I could go?”

She came over and seized me by the elbow. “The hell with Dingus,” she said.

She steered the sheriff’s cruiser along Route 816 away from town and turned north on Ladensack Road. I sat in the backseat and gazed out the window. Darlene had squirreled me out of the jail and grabbed a sheriff’s parka for me out of another car. As we passed Jungle of the North, I remembered turning there to go to Perlmutter’s place and asked where we were going. Darlene didn’t so much as look at me. Another mile ahead, she pulled onto the shoulder, stopped, and shut off the ignition. Seven or eight other cars and trucks were parked there, including my mother’s Jeep.

Darlene got out and came around and opened my door.

“You’re going to get me in trouble,” I said.

“Not if you do the right thing.”

She yanked me out and told me to wait on the shoulder. “Darlene,” I said, “what’s going on?” But she ignored me again and got back into the driver’s seat and snatched up her radio transmitter. I couldn’t hear what she was saying but there was something urgent in the way she shook and nodded her head. She hung up and got out and came around to me with a key in her hand.

“I’m going to take the cuffs off for now,” she said. “Don’t blow it.”

“Why are you doing this?”

“Maybe I’m giving you one last chance.”

We crossed the road and followed a path of freshly trod footsteps that wound through the woods. We emerged in a clearing where a dozen people stood in a circle around a patch of frozen brown earth from which the snow had been dug away. At the center of the patch lay a crude red-and-white container that I would later learn had been fashioned from a scrap of steel cut from the bumper of Ethel, Leo’s Zamboni. It was filled with Leo’s cremated remains.

In their search of Leo’s home, the police had found another, typewritten note in which he had requested that his ashes be scattered on the spot where he and Blackburn had built their midnight bonfires. Leo wasn’t an ironic man, and I couldn’t imagine now that his nostalgia for those nights had been anything but bittersweet. But Blackburn had been his best friend, after all. So there we were: Wilf; Zilchy; Tatch; Elvis Bontrager and Floyd Kepsel and their wives; Francis Dufresne; Judge Gallagher; and my mother, leaning against Joanie. Darlene steered me to the side of the circle facing Elvis and Dufresne. Every one of them looked me over.

“Sorry,” Darlene said. “Please continue.”

“No trouble, darling,” Elvis said. He scowled at me while producing a Bible from under his arm. “We were just getting started.”

If Leo had claimed a denomination, it would have resided in the church of the recovering addicted. He had insisted that no clergy officiate at his funeral and that the service be limited to the reading of a single Biblical passage.

“Blessed are the poor in spirit, for theirs is the kingdom of Heaven…”

The reading finished, Elvis made a few remarks. He called Leo a “pillar of the community” for the many services he had rendered and said his death marked the “passing of an era,” Starvation’s “last days of glory.” Floyd Kepsel talked of how Leo’s gentle nature had complemented Jack Blackburn’s competitive intensity and praised Blackburn for recognizing that Leo could “bring something more to our boys than just the desire to win.” Neither Elvis nor Kepsel alluded to the circumstances of Leo’s death, how he had put a pistol to his temple and pulled the trigger. It was as if Leo had died in his sleep.

Francis Dufresne stepped forward. He clasped his hands atop his gut as he spoke in his hand-me-down brogue.

“This is another terrible day in our great town,” he said. “A good friend—a good man—has fallen. Now I say ‘fallen’ because of course we all know the unfortunate details of Leo’s death, how it shocked us all, how it grieved us to the very core. In a town like this, everyone knows the Zamboni driver, am I right?” A few heads slowly nodded. “But apparently, folks, none of us knew Leo Redpath well enough. And for that we have no one to blame but ourselves. I know I blame myself.”

A sob tried to push up from deep in my belly, but I forced it down and stared hard at Leo’s makeshift urn. I wasn’t thinking about Leo, though. I was thinking about Jeff Champagne, sitting in a jail. I was thinking about that twelve-year-old boy in Escanaba. I was wondering if he played hockey, as Champy did when he was a skinny winger in Starvation Lake trying to land the last spot on the River Rats roster. I was imagining whether that boy looked up to his phys-ed teacher the way Champy once had looked up to Jack Blackburn.

But of course he did.

“It was ten years ago, almost to this very day,” Dufresne was saying, “that we lost our dear friend Jack Blackburn—another good, good man—in a different but equally tragic situation. With due respect to all of you and to the deceased, I would argue, dear friends, that we would not be here today if we had taken better care of our friend Leo in the wake of Jack’s passing.” He paused to look around at the gathering. “In the past week, we have heard much theory and speculation about what happened to Jack and Leo all those many years ago—spurious theory and speculation, if you ask me. Now, I’ve gone back and forth on this, as Augustus here can tell you, and while I appreciate that he has a job to do, and that you, Darlene, and your boss have a job to do, I simply cannot for the life of me see what good any of this prodding and poking of the past has done. Indeed, I’d say it has brought us nothing but grief. I’d venture that we would not be standing here today, with Leo reduced to ashes and Augustus like that and the Campbell boy in jail and Theodore in the hospital if we’d all just left well enough alone.”

“Amen,” Elvis said.

What did Elvis know? Nothing. What did anyone in Starvation Lake really know? I couldn’t blame the people of my hometown anymore than I could blame myself. Most of them were guilty of nothing more than ignorance. They wanted to go on with their lives and hope for the best. Did my father know where his thousand dollars would wind up? Maybe. Maybe not. But I couldn’t save him anymore.

Dufresne unclasped his hands and raised them in front of him. “So now, my friends, I’m imploring you, and everyone in the good town of Starvation Lake, to honor the memory of Jack Blackburn and Leo Redpath by letting them rest in peace. They lived their lives, they were good men—not perfect men, mind you, but good men—and now they are dead and gone.” He looked, in turn, at Judge Gallagher, at Darlene, and at me. “Wherever they are, I am sure they would ask the same simple favor. Let us bury them once and for all today.”

I took a step forward.

Wherever they are,

he’d said. I knew where Leo was. At this moment, I had no idea what had become of Blackburn. There was a truth I had been selfishly trying to deny: Blackburn was still out there, he would not be deterred because he was powerless to deter himself, there were many who would help him carry out his missions, and the terrors he wreaked would be repeated again and again and create more and more ruined boys like Champy and Teddy and Soupy.

“No,” I said.

“Excuse me?” Elvis said. “Deputy, can you control your prisoner?”

“Sometimes,” Darlene said.

“No, by all means, let the boy speak,” Dufresne said. “Augustus knew these men well. Please. Son?”