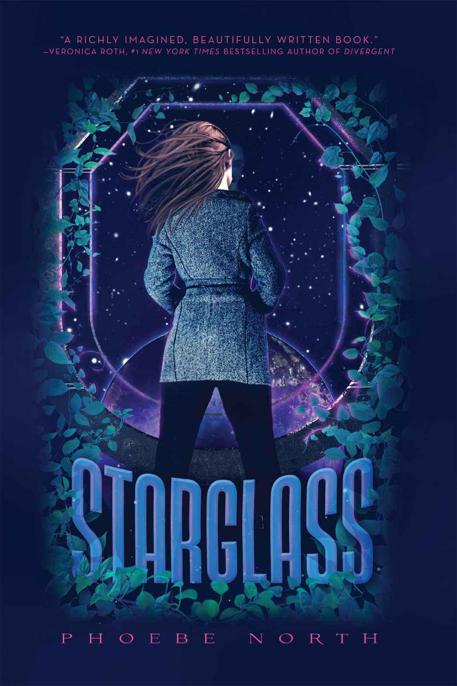

Starglass

Authors: Phoebe North

Tags: #Juvenile Fiction, #Science Fiction, #Family, #General, #Action & Adventure

For Susan Garatino, my fifth-grade language arts teacher, who told me I could write as many stories as I wanted as long as I dedicated my first book to her.

Spring, 467 YTL

My darling daughter,

Know that I never would have left the earth if it hadn’t already been doomed.

They told us that we had five years before the asteroid came. There was no way to deflect it—no way to shield our world. First panic set in, then the riots. They burned buildings down, packed government offices full of bombs. You could walk through the city streets and think the roads were made of broken glass. These were the end times.

At first I was preoccupied. Annie, my lover of thirteen years, was dying. Cancer. And so I ignored the clamoring and the frantic hysteria. I cared for her, bathed her, and spooned her soup until she could no longer eat.

A few days before she went—only hours before she lost all words—she put her fragile hand on my hand.

“Find a way to live on,” she said. “I can’t bear dying if you’re going to die too.”

I loved my home. I loved the way the sky, red with pollution, shivered between the skyscrapers before a storm. I loved the sidewalks, marked with the handprints of people long dead, and I loved how the pavement felt beneath my feet. I loved the feeling of anticipation as I waited in the dark subway station, leaning into the tunnel to watch for the lights.

You’ll never know these wonders. And you’ll never know the way it feels to lie in a field of grass late at night and smell the clover and look up at the sky, wondering at how small you are. Wondering what other worlds are out there.

You’ll know different constellations. And you won’t be tethered to a dying rock. Instead you’ll be up here, among the stars.

Because when Annie left, I went down to the colonization office and signed myself up. The little harried man in the rumpled suit at the front desk said that I was too late. That the rosters were nearly full. He said that my expertise and genetic profile would have to be exceptional for me to be granted passage, said my application was little more than a technicality.

But then he drew blood and had me spit into a tube. Unlike Annie, there was no cancer in my family. No alcoholism. No epilepsy. No stroke. Not even eczema. The little man came back, a clipboard in his hands, and his eyes grew wide.

He told me that I would be placed on the

Asherah—

506 passengers, and me among them, and we would leave for Epsilon Eridani in one week’s time.

And so I prepared to say good-bye.

JOURNEY

MID-SPRING, 4 YEARS TILL LANDING

1

O

n the day of my mother’s funeral, we all wore white. My father said that dressing ourselves in the stiff, pale cloth would be a mitzvah. I ran the word over my tongue as I straightened a starched new shirt against my shoulders. I was twelve when she died, and Rebbe Davison had told us about mitzvot only a few days before—how every good deed we did for the other citizens of the ship would benefit us, too. He said that doing well in school was a mitzvah, but also other things. Like watching babies get born in the

hatchery or paying tribute at funerals. When he said that, he looked across the classroom at me with a watery gleam in his eyes.

That’s when I knew that Momma was really dying.

In the hours after the fieldworkers took away her body, Ronen locked himself in his room, like he always did back then. That left me with my father. He didn’t cry. He wore a thin smile as he pulled off his dark work clothes and tugged the ivory shirt down over his head. I watched him while I held my kitten, Pepper, to my chest. It wasn’t until the cat pulled away and tumbled to the floor that I lost it.

“Pepper! Pepper, come back!” I said, drawing in a hiccuping breath as he scampered out my parents’ open bedroom door. Then I brought my hands to my cheeks. Back then I cried easily, at the slightest offense. Knowing I was crying only made my grief cut deeper.

My father turned to me, the stays on his shirt still undone.

“Terra,” he said, putting a hand against my shoulder and squeezing. My answer was an uncontrollable bray, an animal noise. I let it out. I was naive—I thought that maybe my abba would draw me into his arms, comfort me like Momma would have done. But he only held me at arm’s length, watching me steadily.

“Terra, pull yourself together. You’re soaking your blouse.”

That’s when I knew that he wasn’t Momma. Momma was gone. I brought my hands up to my face, veiling it, as if I could hide behind my fingers from the truth.

After a moment, between my own panted breaths, I heard him sigh. Then I heard his footsteps sound on the metal floor as he drew away from me.

“Go to your room,” he said. “Compose yourself. I’ll get you when it’s time to go.”

I pulled myself up on weak legs. My steps down the hall were as plodding as my heart. When I reached my bedroom door, I launched myself over the threshold and thrust my body down into my waiting bed. Pepper followed me, his paws padding against the dust-softened ground. He let out a curious sound. I ignored him, my hands clutched around my belly, my face pressed against my soggy sheets.

• • •

Usually it was Abba’s job to ring the clock tower bells. But that day, the day my mother died, the Council gave the job to someone else. As we marched through the fields of white-clad people, I couldn’t help but wonder who it was who pulled those splintered ropes. Perhaps my father knew, but his jaw was squared as he gazed into the distance. I knew that he didn’t want to be bothered, so I held my tongue and didn’t ask any questions.

I walked between them, Abba on my one side, his hands balled into fists, and my older brother on the other. Ronen slouched his way up the grassy atrium fields. That was the year he turned sixteen and shot up half a head in a matter of months. His legs were nearly as long

as my father’s by then, and though he seemed to be taking his time, I had to scramble to keep up.

The bell tolled and tolled beneath a sky of stars and honeycombed glass. Underneath the drone of sound I heard words—murmured condolences from the other pale-clothed mourners.

By then we’d learned in school about Earth, about the settlements that had held thousands and thousands of people. They called them “cities.” I couldn’t imagine it. Our population was never more than a thousand, and so the crowd of people—a few hundred, at least—felt claustrophobic. But I wasn’t surprised by the throng of citizens that gathered in the shadow of the clock tower. Momma had been tall, lovely, with a smile as bright as the dome lights at noon. She’d made friends wherever she went. As a baker, working at a flour-dusted shop in the commerce district, she had encountered dozens of people daily.

Everyone wore white. On a normal night we’d be dressed in murky shades of brown and gray, the only flashes of color the rank cords the adults wore on the shoulders of their uniforms. But there were no braided lengths of rope on our mourning clothes. Rebbe Davison said that rank didn’t matter when we grieved.

“Terra! Terra!” A voice cut through the crowd. My best friend Rachel’s lips were lifted in a grim smile, showing a line of straight teeth. She was the kind of person who couldn’t stop herself from

smiling even at the worst times, especially in those days before she started saving most of her smiles for boys.

I moved my slippers through the muddy grass, afraid she might apologize, offer empty words like all the others had done. But she only reached out and took my hand in hers. As we walked across the field together, she looped her pinkie finger around mine. We neared the clock tower and the grave dug deep below it; her hand offered a small, familiar comfort.

When we reached the grave, she pulled away. She gave my fingers one final squeeze, but she had to go join her family, and I had to join mine. I watched her leave. At twelve she was already willowy and lean, and her dark skin seemed to glow against her dress in a way that reminded me of freshly turned soil. I knew that in comparison I was little more than a shadow, faded and pale, my complexion sallow and my dirty-blond locks stringy from tears.

This is why I was surprised when I turned and saw a pair of black eyes settle on me. Silvan Rafferty was watching me. He was my age, in my class. The doctor’s son. His lips were parted, full and soft. I hadn’t told anyone yet, but I knew those lips. Only a few days before, Silvan had followed me home after school.

That afternoon he’d called out to me across the paths that spiraled through the dome. At first I blushed and walked faster, sure he was only teasing. But then he broke into a jog, his leather-soled shoes

striking the pavement hard. When he neared me, he reached out like he meant to take my hand.

“I heard your mother is sick,” he said. “My father told me. I’m sorry.”

I wouldn’t let his fingers grace mine. Abba had always said that good girls didn’t hold boys’ hands until they were older and ready to marry. I didn’t want to give Silvan the wrong idea. We’d never even spoken before that day.

“It’s all right,” I told him, fighting the strange desire to comfort him. His eyelashes trembled. He looked so

sad

. I didn’t want to be pitied. So I did the only thing I could think of—I stood up on my tiptoes and pressed my mouth to his.

It was a quick kiss, closed-mouthed, but I could smell the sharp scent of his breath. He tasted like strong tea and animal musk. He leaned in . . . then I pulled away.

“I have to go,” I said, trying to ignore the heat that spread over my ears and face. “They’re waiting for me at the hospital.”

As I walked I didn’t look back. I thought of the things Abba had always told me about being good, about not giving boys the wrong idea. Over the dinner table Momma scolded him.

Don’t be so old-fashioned, Arran,

she always said. Perhaps she was right. Even Rebbe Davison said that there was nothing wrong with going with boys, once they’d had their bar mitzvahs. And Silvan was nearly thirteen. Still, Abba insisted

he knew better. He’d

been

a boy, after all. And standing there, still and stupid and blushing at my mother’s funeral as Silvan’s eyes pressed into me, I wondered if he was right. This was no time for flirting. It was time to do my duty, to be an obedient daughter.

Abba and Ronen stood at the head of the crowd. I drew in a breath as I pushed through the crush of bodies. My mother waited in the black earth, her body wrapped in cloth. I told myself it wasn’t her, that all those stories about how the dead wandered the atrium dome on lonely nights were just kids’ stuff. Momma was gone, and this was only flesh. But I couldn’t deny the familiar shape of her—her long thin figure—underneath the cotton wrappings.

My throat tightened. I squeezed myself between Abba and Ronen, doing my best to resist taking either of their hands.

It’s a mitzvah,

I told myself.

To be brave. To be strong. To stand alone.

And then I cast my gaze up to my father to see if he noticed how hard I worked to keep my trembling mouth still. But his eyes were just fixed forward.

The sound of gossip crested beneath the bell’s final toll. I watched as the crowd parted, making way for the captain’s guard. The square-shouldered soldiers were dressed in funeral whites, ceremonial knives dark and glinting against pale cloth. As they marched, their boots drummed like rain against the grass.

In their wake Captain Wolff appeared. Everyone pressed two fingers

to their hearts in salute. But my own fingers hesitated at my side.

I knew that I was supposed to believe that Captain Wolff was brave, noble, and strong. She’d instituted the search for capable shuttle pilots, lowered the sugar rations to make room for more nutritious crops, and raised the number of guards to almost fifty in order to better keep peace among the citizens. Her leadership skills and self-sacrifice were going to lead us straight to Zehava’s surface. It was treason to think otherwise.

But she frightened me. She always had. Whether staring back at me from the pages of my schoolbooks or making speeches to a crowd, her sharp, hawkish features and her long, white-streaked hair always moved a shiver down my spine. Perhaps it was the scar across her face, a gnarled line that ran from her left cheekbone to her chin. They said it was from an accident when she was small—she’d saved a boy who’d gotten caught up in a wheat thresher in the fields. That noble act had been the first thing she’d ever done for the good of the ship, and the scar, a memento of her bravery.