Stalking Nabokov (40 page)

Having concluded that it was impossible to translate poetry

as

poetry with total fidelity to both sense and verse form, Nabokov at the end of the 1960s decided to show the exception that proved the rule by composing a short poem simultaneously in English and Russian with the same complex stanza structure: a poem about the very act of walking simultaneously on these two separate linguistic tightropes, each swinging to its own time. Even he found he could write only stiltedly under these disconcerting conditions, and he wisely abandoned the effort.

Much more successful was his earlier attempt to create in English two stanzas in the strict form that Pushkin created for

Eugene Onegin

, in a poem about his translating

Onegin

. Pushkin’s fourteen-line

Onegin

stanza ingeniously reworks the pattern of the sonnet so that, as Nabokov notes, “its first twelve lines include the greatest variation in rhyme sequence possible within a three-quatrain frame: alternate, paired, and closed.”

13

The stanza offers an internal variety of pace, direction, and duration that forms part of the poem’s magic for Russian readers. To show non-Russian readers the variability of this variety, Nabokov composes two stanzas in English that, like Pushkin’s, modulate tone, pace, subject, imagery, and rhyme quality within the stanza and from stanza to stanza, so that the stanzas are both self-contained and internally changeable and, in the movement from one to another, both continuous and contrasting. The first quatrain of stanza 1 stops and starts, with question and answer after abrupt dismissive imagistic answer; the first quatrain of stanza 2 skims on unstopped, like a camera zooming through a fast-forward nightscape. Nabokov knows he cannot combine Pushkin’s sense and pattern while exactly transposing Pushkin’s precise thought into the different structures and associations of English, but at least he can impart to Anglophone readers a sense of the coruscating enchantment of Pushkin’s stanza form.

On Translating “Eugene Onegin”

1

What is translation? On a platter

A poet’s pale and glaring head,

A parrot’s screech, a monkey’s chatter,

And profanation of the dead.

The parasites you were so hard on

Are pardoned if I have your pardon,

O, Pushkin, for my stratagem:

I traveled down your secret stem,

And reached the root, and fed upon it;

Then, in a language newly learned,

I grew another stalk and turned

Your stanza patterned on a sonnet,

Into my honest roadside prose—

All thorn, but cousin to your rose.

2

Reflected words can only shiver

Like elongated lights that twist

In the black mirror of a river

Between the city and the mist.

Elusive Pushkin! Persevering,

I still pick up Tatiana’s earring,

Still travel with your sullen rake.

I find another man’s mistake,

I analyze alliterations

That grace your feasts and haunt the great

Fourth stanza of your Canto Eight.

This is my task—a poet’s patience

And scholiastic passion blent:

Dove-droppings on your monument.

(

PP

175)

Third,

Verses and Versions

offers another facet of one of the greatest and most multifaceted writers of the twentieth century—not only a major author in two languages and in fiction, nonfiction, poetry, and drama but also, as readers have come to realize, a world-class scientist, a groundbreaking scholar, and a translator.

Nabokov once said that he called the first version of his autobiography

Conclusive Evidence

because of the two

V

s at the center, linking Vladimir the author and Véra the anchor and addressee, as she proves to be by the end of the book.

Verses and Versions

similarly links Vladimir and Véra, who wanted to assemble a book like this as a monument to her husband’s multifacetedness. It also pays homage to

Poems and Problems

, which, late in his career, introduced readers to Nabokov’s Russian verse as well as his English and to still another facet of his creativity, his world-class chess-problem compositions.

Pushkin has a special place in the hearts of all Russians who love literature. He has a particularly special place for Nabokov in his Russian work (Pushkin is the tutelary deity of his last and greatest Russian novel,

The Gift

, which even ends with an echo of the ending of

Eugene Onegin

, in a perfect Onegin stanza, cast in prose) and in his efforts as an English writer to make Pushkin known. Pushkin is also a byword for the untranslatability of poetic greatness: unquestioned in his preeminence in his native land yet long almost unrecognized within any other. Flaubert, one of the brightest stars in Nabokov’s private literary pléiade, famously remarked to his friend Turgenev: “He is flat, your poet.”

Nabokov himself discusses the untranslatability of one of Pushkin’s great love lyrics in the first of his essays on translation. I would like here to consider

another

great love lyric, “Ya vas lyubil” (“I loved you”), which Nabokov translated three times, in three different ways: in an awkward verse translation of 1929 and in a literal translation and a lexical (word for word) translation, accompanied by a stress-marked transliteration and a note, about twenty years later. None of these quite works (the lexical is not even meant to work, merely to supply the crudest crib); none of these can quite convince the English-language reader that this is one of the great love lyrics— one of the great lyrics of any kind—in any language.

Yet Nabokov is not alone. For the bicentennial of Pushkin’s birth—and coincidentally the centennial of Nabokov’s—Marita Crawley, a great-great-great-granddaughter of Pushkin and chairman of the British Pushkin Bicentennial Trust, asked herself how she could convince the English-speaking public that Pushkin’s genius is as great as Russians claim. She answered herself: she would invite a number of leading poets to “translate” Pushkin poems, or rather to make poems out of Pushkin translations. In a volume for the Folio Society, she includes poets of the stature of Ted Hughes, Seamus Heaney, and Carol Ann Duffy. Duffy took “Ya vas lyubil”:

I loved you once. If love is fire, then embers

smoulder in the ashes of this heart.

Don’t be afraid. Don’t worry. Don’t remember.

I do not want you sad now we’re apart.

I loved you without language, without hope,

now mad with jealousy, now insecure.

I loved you once so purely, so completely,

I know who loves you next can’t love you more.

Duffy is a fine poet, but I suspect few will think this one of literature’s great lyrics—not that she is not as successful as other poets in

After Pushkin

.

14

What is it that makes Pushkin’s poem great?

I offer a plain translation into lineated prose:

I loved you; love still, perhaps,

In my heart has not quite gone out;

But let it trouble you no more;

I do not want to sadden you in any way.

I loved you wordlessly, hopelessly,

Now by timidity, now by jealousy oppressed;

I loved you so sincerely, so tenderly,

As God grant you may be loved by someone else.

My translation, if undistinguished, is acceptable, though I almost sinned by ending, “As God grant you may be loved again.” In Pushkin the last word is “

drugím”

and means “by another” (in context, “by another man”): “As God grant you may be loved by another.” I should not have thought of closing with “again” and would not have done so had I not been intending to supply a literal translation and a lexical one. On its own, “again” might be ambiguous, might suggest the speaker has perhaps ended up anticipating a complete revival of his own feelings. What is needed is a short, strong, decisive ending, and “again” at first seemed to supply some of this, though without the shift and precision of thought and feeling in Pushkin’s “

drugím

,” where “As God grant you may be loved by another” ended too intolerably limply for me to tack it to the rest of the translation.

The poem starts with what might seem banal, “Ya vas lyubíl,” except that it is in the past, and that gives it its special angle. As Pushkin treats of the near-universal experience of having fallen out of love, he gradually moves from the not unusual—the change from present love to near past, the aftershock of emotions, the shift from desire to tender interest and concern—to the unexpected closing combination, the affirmation of the past love in the penultimate line, “I loved you so sincerely, so tenderly,” then to the selfless generosity of the last line, the hope that she will be loved again as well as

he

has loved her, which in its very lack of selfishness confirms the purity of the love he had and in some sense still has.

Where Duffy’s “who loves you next” almost implies a line-up of lovers, Pushkin offers a surprise, yet utter emotional rightness and inevitability. Where Duffy’s line becomes a near boast, emphasizing that the speaker’s love is unsurpassable, Pushkin’s speaker dismisses self to focus on and pray for his former love.

This is what Pushkin is like, again and again. He cuts directly to the core of a human feeling in a way that makes it new and yet recognizably right and revelatory. He creates a complex emotional contour through swift suggestion, a scenario all the more imaginatively inviting by being unconstrained by character and event. His expression seems effortless and elegant, but his attention and ours is all on the accuracy of the emotion. In this poem Pushkin allows just one shadow of one metaphor, in the verb in the second line,

ugásla

, which can mean “gone out” or “extinguished,” where Duffy feels the need to embellish and poeticize the image into “If love is

fire

, then

embers /

smoulder

in the

ashes

of this heart,” with a pun on “heart” and “hearth.” This is inventive translation, but it is not Pushkin’s steady focus on feeling. Duffy’s lines draw attention to the poet, to the play. In other moods Push-kin can himself be supremely playful and playfully self-conscious in his own fashion, but here he offers an emotional directness and a verbal restraint amid formal perfection that is alien to English poetry and that to Duffy feels too bald to leave unadorned.

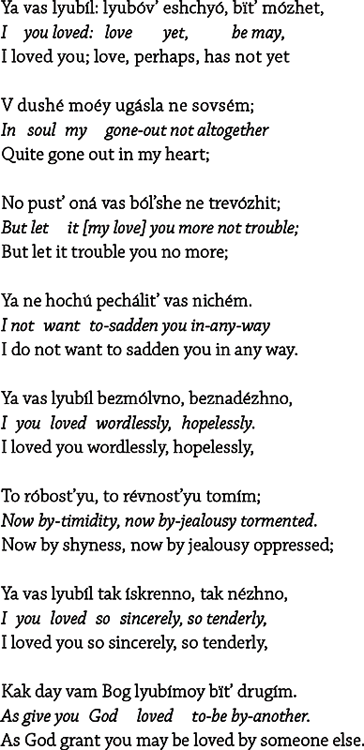

With your attention now engaged, ready to slow down and savor this poem, I offer below Pushkin’s own words, transliterated and stressed, with an italicized word-for-word match below (a “lexical translation” in Nabokov’s terms) and my strictly literal translation below that.