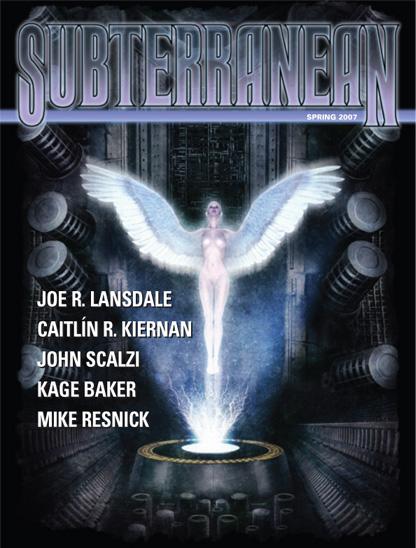

Spring 2007

Authors: Subterranean Press

Winter 2007

In

this Issue:

The following features are in this issue:

•

Column:

Bears Examine #2 by Elizabeth Bear

•

Column:

Bears Examine #3 by Elizabeth Bear

•

Column:

HARVESTING THE DARKNESS #2: FULLY STOKE(re)D by Norman Partridge

•

Column:

Me and Lucifer by Mike Resnick

•

Fiction:

A Plain Tale from Our Hills by Bruce Sterling

•

Fiction:

A Season of Broken Dolls by Caitlin R Kiernan

•

Fiction:

Deadman’s Road by Joe R. Lansdale

•

Fiction:

Eating Crow by Neal Barrett, Jr.

•

Fiction:

Jude Confronts Global Warming by Joe Hill

•

Fiction:

Missile Gap by Charles Stross

•

Fiction:

Pluto Tells All by John Scalzi

•

Fiction:

The Leopard's Paw by Jay Lake

•

Fiction

The Lost Continent of Moo: A Lucifer Jones Story by Mike Resnick

•

Review:

Jack Knife and Map of Dreams

•

Review:

Nebula Awards Showcase 2007 edited by Mike Resnick

•

Review:

On the Road with Harlan Ellison volume 3

•

Review:

Softspoken by Lucius Shepard

•

Review:

The Last Mimzy by Henry Kuttner

•

Review:

The Yiddish Policeman's Union By Michael Chabon

•

Review:

White Night by Jim Butcher & Wizards edited by Jack Dann and Gardner

Dozois

•

Review:

The Best of the Best Volume 2 20 Years of The Best Short Science Fiction

Novels

•

Review

: Harlan Ellison's Dream Corridor Volume 2

Column:

Bears Examine #2 by Elizabeth Bear

I hate the word ought, and I hate blanket imperatives.

For that reason, I am

not

about to say that every aspiring writer really

ought to spend a year reading slush.

But I will say that aspiring writers can

learn

by

reading slush. For one thing, it will show you what everybody else is doing,

and maybe why it’s not such a great idea for you to do exactly the same thing.

But moreover, you will learn something more important to

your development as a writer.

You learn why editors reject stories.

And editors reject stories for very simple reasons.

Essentially, it boils down to one thing (sort of like the old joke that Cause

of Death is really always the same: “lack of oxygen to the brain”) if a story

is rejected, it’s because the story failed to enthrall the editor.

I still read slush, for the online ‘zine

Ideomancer.

I don’t get paid to do it. I’m not the person who makes the final editorial

decisions. I am just the Cerberus at the gate, the person you have to get past

to get to the people who will actually decide if we are going to publish you.

And they reject most of what I send up, because I don’t

actually have to love everything I pass along. I just have to get to the end

and not roll my eyes.

I’m going to be candid. The eyeroll is when I reject.

It’s my red line of death. (Damon Knight used to draw a line on critique

manuscripts to indicate the point at which he rejected them.)

The moment I send a story back whence it came is the

moment when I take a breath and think, “Why am I reading this?”

The main thing an editor cares about is if the story

keeps her reading.

And that’s it. That’s all you have to do. You’re not

being graded on a curve. You’re not being graded pass/fail. You are not, in

fact, being graded.

In other words, you don’t have to be “good enough.”

There is no such thing as good enough. It doesn’t matter what your writing

group is doing, either: this is not about peer promotion; it’s about

entertainment.

If you can entertain, you get the job.

If you can’t… the job goes to somebody who can. Because

the slush reader’s job is to anticipate the entertainment reader. The end

consumer. The guy who buys the book.

That reader is an entirely selfish beast, you see, and

he doesn’t owe the writer anything. An inconvenient fact, and one I find a

tremendous frustration, but there you go. He’s the one with the money in his

pocket; he is completely in control of the relationship.

This doesn’t mean that you should let him run your life,

though. Because this is where artistic integrity comes in.

As a writer, you have to be able to set limits on what

you are or are not willing to do. I personally would recommend not writing

anything you’re not sufficiently passionate about to really

want

to

write.

And readers, in addition to being fickle, are psychic.

They can tell if you don’t care. Not-caring is boring.

And if the slush reader is bored, the regular reader is going to be bored too.

The bad news is, not-caring is not the only form of

being boring. My slush is full of stories about which the writer obviously

cares deeply. Those may be unpublishable for a variety of other reasons.

As a slush reader, I have a list of other things that I

have come to find boring. Preachiness is boring. Predictability is boring.

Twist endings are boring.

Most of the things aspiring writers do to punch up the

beginning of a story are boring. (Explosions, sex, shocking revelations, the

inevitable heat death of the universe.) All that stuff is

boring.

So what’s a writer to do?

Here’s the counterintuitive thing. A story can be

incredibly engaging from word one, even if it starts with a great big wodge of

exposition.

Because what pulls us into the story is the narrative

urgency, the drive, and the disconnect. The little mystery, the incongruity…

and the writer’s voice. That’s the dirty secret: what keeps you reading, as an

editor, is whether or not the writer can rub words together.

The good news is, this is a learnable skill for most

people. Just like juggling. And just like juggling, it’s not easy. And requires

years of practice.

A lucky few come in gifted in terms of voice, but they

generally have other problems–and their problems may be harder to

address, because it’s my completely unscientific experience that those writers

start selling sooner, and so may have less motivation to push themselves and

keep pushing.

Voice, in other words, is the thing that emerges when

one has written one’s million words for the trunk. (Mine was considerably more

than a million. Just so you know.) The horrible thing about the million words

is that you can’t write them expressly for the trunk. You never learn that way,

just writing bad words. You have to push for the best words, bleed for them,

train yourself to exceed your current limits.

It’s hard.

And as far as I know, there is no shortcut.

But there is that other thing I mentioned. The

disconnect. The incongruity. It’s not the lake of blood or the masturbating

vampire on page one that will keep a reader engaged in the story. (Actually,

come to think of it, a masturbating vampire might just do the trick. I don’t

see those every day. [Every slush reader in the business is cursing my name

right now, FYI.])

What I mean is, what pulls

a slush reader into a story is a certain vividness, of prose and image, of

character and action. And that little thing that niggles, that you have to keep

reading, to find out about.

Column:

Bears Examine #3 by Elizabeth Bear

I come not to satirize Truesdale, but to bury him.

When Bill Schafer asked me to write these columns, he

also mentioned that he’d like it if I could be as outrageous and topical and

argumentative and controversial as possible. I’m honestly a pretty phlegmatic

soul about most things, and I cautioned him that I wasn’t sure how much of that

I could manage, really.

Well, you know. I

could

talk about the Hugo

Ballot, and whose fault it is that there aren’t many women on it (1). And the

Philip K. Dick Award, and why there aren’t many men on it. (2)

I could talk about how the Hugos are decided by a small

group of dedicated fans of a certain age, who have well-established favorites,

and who have a lock on the award for as long as they continue voting, because

they

are

the ones voting. I could talk about the apparent trend that

books nominated for the Hugos are those released in hardcover, and the

perception that women writers are more likely to be released in paperback. I could

speculate on whether this is due to their readerships, the coincidence of

editorial tastes, the sort of topics that women writers trend to, the business

models of the publishing houses that feature a preponderance of women writers,

or the intersection of all of the above.

I could talk about why Chris Moriarty isn’t in

hardcover, say.

I could talk about my inexpressible relief that Dave

Truesdale can’t be arsed to read my books, especially when he considers calling

some of the top women writers in SFF a bunch of pussies to be somehow

satirical. I could talk about Adrienne Martini’s apparently bottomless

ignorance of the Hugo nominating process. I could talk about whether or not a

major genre magazine is undermining its credibility by featuring a columnist

who by his own declaration isn’t a “writer.”

I could suggest that, as a genre, or a critical

discussion, or whatever, what we really need is some satirists who are

actually, you know,

funny.

I could.