Spice and the Devil's Cave (20 page)

Read Spice and the Devil's Cave Online

Authors: Agnes Danforth Hewes

He started guiltily â Ruth was speaking, looking up from her work. Had she seen him watching those two outside? But she was only saying that the brass map-containers would soon need polishing.

Nicolo caught at the cue to cover his silence, and asked Abel where he got them.

“Scander attends to that,” Abel replied. “He knows someone in the locksmith business.”

Scander laughed, a little sheepishly. “Seems odd that one who's followed the sea all his days can settle down to land jobs!”

“Don't you think you'll ever change your mind,” Nicolo pressed him, “and go as pilot to one of our fleets?”

“Not me!” The tanned face seemed to settle into its wrinkles. “I'm like a dog that's come back to his old kennel, and I reckon â” he chuckled, as if amused with the figure, â” I reckon I'll play watch dog the rest of my days!”

For a moment Nicolo fancied that Scander's gaze sought the court. Did he mean “play watch dog” to Nejmi? Yet why should she need to be guarded, surrounded as she was by the adoration of them all?

His own gaze followed Scander's. Ferdinand, he perceived, had gone, and Nejmi was kneeling by a bed of thyme, loosening the earth. On the impulse he got up, and went into the court. No more dallying, no more inward debate.

“I sometimes think,” he said, going straight up to her, “that you'd rather not talk to me â alone.”

Silent, startled, she looked at him. “What would you like to talk about?”

He could have ground his teeth at her adroit but complete parry. “That isn't my point, and â” plunging boldly â“yon know it!”⦠How would she meet that?

But she only loosened more earth and heaped it around the roots, and at last it came over Nicolo that she was not going to answer him, that she was making a fool of him â or had he made one of himself? He angrily cast about for a pretext to argue with her.

“Is it that â that money I paid for the sugar-debt, you called it â that makes you keep at a distance?”

She raised her eyes to his. “It did make me feel uncomfortable, at first,” she admitted, “but not any longer. Besides â” she flushed brilliantly â“I'm going to pay back that debt!”

“Don't!” he managed to say. “Don't talk that way, Nejmi!”

She continued to look at him, then bent again to her work. “You want me to pay you!” she breathed, hardly above a whisper.

He started back as at a blow â the more cruel that, for a fleeting instant, he could have sworn that laughter had lurked in her eyes.

In a daze he heard Scander at his elbow: “Going along, now, sir? I'll walk with you to the turn of the street below.”

Mechanically, Nicolo murmured good-bye to Abel and Ruth standing together in the workshop door, and then he and Scander started down the long stairway. Through the chaos of his brain he became aware of Scander's voice insistently dwelling on a word, a familiar word:

Venice

.

“A bad business,” he was saying, “that Ferdinand was telling us about Venice.”

A vague recollection stirred Nicolo's memory. What was it Ferdinand had said? In a flash it came to him:

Venice ⦠the Oriental trade . . . and that gossip about Egypt.

Ah, but those other things that Ferdinand had said: “Where Sunset takes Dawn in his arms . . . their flaming kiss ⦔

There was no forgetting those things!

CHAPTER l6

Abel Visits the Palace

I

N

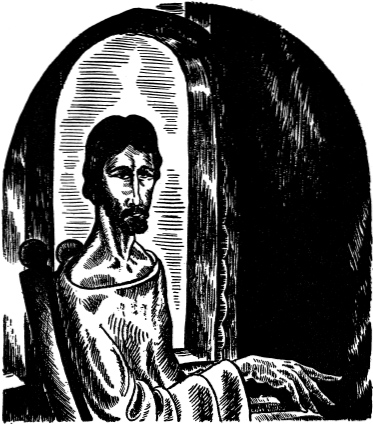

his long, black cloak and his conical, narrow-brimmed hat, Abel stood in a corner of the small room that Manoel used for informal audiences. He had expected to see Ferdinand, but Ferdinand was nowhere about, and another page had shown him where to wait until the King should be ready to see him.

He had been a little startled to find himself at once in Manoe's presence, though Manoel hadn't appeared to pay any heed when he entered. In fact, all that did seem to concern Manoel was keeping cool, and getting rid, as fast as he could, of the courtiers and pages who came and went around him. Half-dressed in a thin, silk lounging robe, he sat by an open window and spasmodically fanned himself with his handkerchief, for these days it was hot even by mid-morning.

Abel watched with amusement the dextrous way he managed to greet each visitor and, almost in the same breath, to wave him on. No one was encouraged to linger. Once, a good-looking young fellow in uniform, perhaps one of the aides, hurried in and whispered something. Abel saw Manoel frown, and, for a minute or two, one hand nervously clenched and unclenched. Then, he suddenly glanced up and, as it seemed to Abel, directly at him â or had he only imagined it? Manoel then turned to the young man, merely nodded, and went on fanning himself, while his visitors continued to file past.

Abel wondered when his own turn would come. As a matter of fact, his standing here so patiently, indeed his being here at all, struck him as grimly humorous, for when Ferdinand had hinted at Manoe's sending for him, he'd virtually said he wouldn't go. Then, as he had pondered the matter, something decided him to go-something that had troubled him for a long time: why did his people delay their going, postpone the exodus that finally they must face? How could they be roused from the apathy into which they'd sunk to see that anything was better than staying on, dishonoured and outcasts, where once they'd been free citizens? For Nejmi, and Nejmi only, he and Ruth had stayed, but now . . . Suppose, Abel had meditated, suppose, all unconsciously, Manoel could be manoeuvred into some measure that would so rouse the Jewish spirit, that. . . Yes! if he were summoned to the palace, he'd go!

He studied the figure by the window. It was hardly material to be “manoeuvred” into anything! Under the thin robe the lean, sinewy body was easily visible. Well, there was nothing in the way of physical toughening it hadn't gone through, and if the man within were as hard and unyielding as the man without . . . Almost ludicrous, the lanky arms were, in those flowing, feminine sleeves; the lanky arms whose fingers, it was Manoel's boast, could more than touch his knees when he stood upright â and that people said were a sign of his grasping nature! His face was as young as his less than thirty years, if one judged by the texture of the smooth, dark skin and the carefully parted hair and the crisp, short beard. But the expression in the odd, greenish eyes was that of a man far older. A man who was used to winning his game, and expected no opposition while he won it. One who expected to move his pawns without interference.

The procession of visitors was now dwindling. Abel saw the greenish eyes fix on a page, and a hardly perceptible lift of the brows. At once the boy came and whispered, “The King will see you now.”

Deliberately Manoel turned from the last lingerers, who seemed to understand their dismissal, and forthwith left the room.

“Close the door after you,” he said to the page. “When I wish you, I'll rap.”

He surveyed Abel attentively, then he motioned toward a chair. “Make yourself comfortable, Master Zakuto,” he graciously told him. “I'm right, am I?” he added. “You're Abel Zakuto, kinsman of Abraham?”

Without changing his position, Abel nodded. “I've stood since I came in,” he said, pointedly. “I'll remain standing. Yes, I'm Abel Zakuto.”

For a moment this answer seemed to disconcert Manoel, then, “Well â please yourself!” he laughed.

He turned toward the open window, and absently gazed into the gardens beyond, and again Abel observed that nervous clenching and unclenching of one hand, while the other, holding the handkerchief, lay idle. A bumble bee flew in and buzzed about Manoel's head, but he took no notice of it.

“I sent for you, Master Zakuto,” he said, facing back to the room, “because I understand that you, like your kinsman, Master Abraham, are skilled in the science of the stars.”

He paused, as if for Abel to reply, but as Abel appeared to have no such intention, Manoel went on, while he rapidly fanned himself.

“You know, of course, that the people are beginning to doubt Senhor Gama's return. It's bad for the country, such a state of mind.”

This time his eyes openly sought a response, but still Abel continued impassive.

“The worst of it is,”â Manoel confidentially lowered his voice â“they're openly mentioning in certain foreign countries our fears for Gama.”

“Aha!” thought Abel, recalling Ferdinand's talk of the other day, “I wonder if that means Venice.”

“Now,” Manoel said, “if we could give out a statement that the stars are favourable to his return â as they were to his going. . . . You see why I sent for you, Master Zakuto!”

The stars indeed! Inwardly Abel chuckled, as a certain night in the workshop, with Nejmi surrounded by an awestruck group, flashed across his memory.

Aloud, he said, “My only business with the stars, Your Highness, is to learn from them a little navigation.”

There was an impatient gesture, and the handkerchief dropped to the King's lap. “Surely you understand them as well as Master Abraham did?”

“Beyond a few matters of celestial degrees and computations, no.”

Manoel thoughtfully regarded Abel, then, once more, his eyes sought the open window, and Abel saw that same perplexed frown as when the good-looking young aide had whispered a message. The room was very still, but the jessamine vine at the casement swayed in the warm breeze. A restless hand clenched and unclenched.

“Master Zakuto, I spoke of the rumour, in certain quarters, that we've given up Senhor Gama.”

The King, Abel perceived, was choosing his words so as not to disclose too much.

“Unless we can give that rumour the lie, it may cause us trouble. In fact â” bringing a fist down on the chair arm â“it

is

causing us serious trouble. We must stop it. Suppose, Master Zakuto,” his tone almost entreated, “I should make it worth vour while to say Gama would return?”

Abel's face flashed. “As you made it' worth while' for Abraham?” For a breathless instant he paused, almost expecting to be struck down for his temerity. But having gone this far, let him go all the way: “As you made it âworth while' for the race who've built the prosperity of Portugal?”

Manoel's eyes dropped. “That measure was â was most unfortunate â most regrettable,” he unexpectedly conceded, “but sometimes the State demands the sacrifice of the individual. If, for the good of the country, you could see your way clear . . .”

Abel studied, with a little less hostility, the tense figure opposite him. Did Manoel really feel sorrow at what he'd done, really “regret” it? Certainly his patience this morning had been past belief â no sovereign had ever borne as much from a belligerent subject! And after all, he was the sovereign. Ah, but the bleeding hearts and the broken lives that he had been willing to pay for his Spanish wife â and Abel hardened his heart.

“Why should âthe good of the country' concern me, now, Your Majesty?” he coldly asked. Dear Portugal, forgive him that!

The greenish eyes glinted unpleasantly. “If that's your feeling, I'd best clear the country of all you Jews â” he snapped his fingers â“like that!”

Inwardly Abel smiled. He was doing well! But he must do better, prick deeper. He feigned indifference. “That's within your power,” he quietly replied. “But, Your Majesty, you'll find that Portugal will need her Jews more than they will ever need her!”

“By Saint Vincent!” Manoel choked out from deep down in his throat, and Abel could see that the fingers gripping the chair were twitching. Unconsciously he braced himself, for the fury in those green eyes brought to mind something that struck and clawed.

Suddenly, the fury faded, the fingers relaxed. Again Manoel lolled carelessly in his chair, and again began his lazy fanning.

“Then, perhaps, Master Zakuto,” he said, maliciously, “I'll keep that valuable race of yours with me â forbid any of you to go!” He reached out and rapped on the door, and as the page outside opened it, “Show this person out,” he said, without again glancing toward Abel.

His mind considerably bewildered, Abel walked through one corridor, and into another. Uniformed figures hurried past, but he was too busy with his thoughts to notice them. Where was this thing that he had started going to end? And why had Manoel let him go free? It was the first time, Abel was willing to wager, that young man had listened to such plain talk, and on the whole he'd not done so badly with his insulted dignity. But if he could know that, for once, he'd danced the puppet while a hand other than his pulled the strings! Now, if only he would carry out his threat and tell his Jewish subjects not to do what they had the right to do! . . . But even as Abel exulted within himself, he groaned: what had he, Abel Zakuto, brought on his people?

Ahead of him he saw the exit, and a sudden hankering seized him for the streets beyond it, the narrow twisting streets, the clatter of donkey hoofs, the cries of the vendors, the smell of fruit and vegetables in the hot sun.