Southern Storm (25 page)

Authors: Noah Andre Trudeau

Lieutenant General William J. Hardee was not alone in concluding that with Macon now safely behind Sherman’s advance, Augusta was the likely target. The telegraph lines between that city and Richmond hummed with urgent traffic. Jefferson Davis sent two messages. One directed that as much valuable machinery as possible be dismantled for relocation to a safer place. The other underscored the Confederate president’s determination to cut Sherman off from any sustenance. “All supplies which are likely to fall into the enemy’s hands will be destroyed,” he commanded.

Still lacking any substantial reinforcements to send to the region, Davis continued his “great men” policy by assigning another notable to the trouble spot. General Braxton Bragg, then overseeing C.S. affairs in North Carolina, received instructions to proceed to Augusta “to direct efforts to…employ all available force against the enemy now

advancing into Southeastern Georgia.” Stopping the enemy effort to capture Augusta was Davis’s top priority; as he said, “every other consideration will be regarded as subordinate to that.”

A similar sense of urgency now prompted a veteran officer in Augusta to make his own effort to cut through the tangle of semi-autonomous commands scattered before Sherman’s columns by placing himself in charge. Ambrose Ransom Wright had been a brigadier in Robert E. Lee’s army with service at Antietam, Chancellorsville, and Gettysburg. He was no stranger to controversy, having released a public letter after the latter battle that was harshly critical of several of his peers.

Wright, vindicated at a subsequent court-martial, left the army to win a seat in the Georgia legislature, eventually rising to the position of president of the Senate, making him second in line in order of succession. From where Wright sat, Governor Brown was “disabled” by being cut off in Macon, thus activating a clause in state law empowering him to step in. “I have assumed command of the militia of the State east of the Oconee River, and have ordered all able-bodied men to report to me here,” he informed the officer in charge of troops around Savannah.

Wright’s move infuriated Governor Brown’s partisans, who viewed the action as a blatant attempt to subvert the state’s gubernatorial authority. “I need scarcely say that disability is a legal term signifying legal incapacity to do an act—not mere temporary physical hindrance,” fumed a lawyer on the scene. The resulting clamor prompted Wright to transmit a request for Brown’s approval of his action, something that the governor would not even consider granting. Communication, Brown pointed out, was not disabled, only “lengthened,” and therefore did not invoke the “contingency contemplated in the [State] Constitution.” Wright’s action, while well-meaning, only compounded the confusion.

Confederate response continued to be hampered by the gap at the top. Beauregard, still heading toward Macon, was not in contact with a working telegraph line. Hardee, as one subcommander put it, “was at Macon on Sunday; have not heard from him since.” Ripples of panic spread as far as Charleston, where the officer in charge of the post earnestly pleaded with Richmond for reinforcements to meet Sherman’s expected assault.

While the top brass dithered, the local press beat the drums of war. In Augusta, the morning newspaper proclaimed that “Georgia’s hour of trial has come.” Confronted by the Federal depredations, the state’s residents faced “the single choice between victory and ruin.” Declared the editor of the

Augusta Daily Chronicle & Sentinel:

“There is no alternative left them but to fight.”

One area in which Confederate authorities performed with admirable promptitude was the evacuation of Camp Lawton, in business only since early October. Camp authorities had been given permission to ship the prisoners elsewhere on November 19. Camp Lawton’s commander reported today that the facility had been completely emptied save for “a few shoemakers and butchers, who will leave in the course of a few hours.” The movement of some 10,000 men had been carried out in such a manner that no word of it reached Major General Sherman near Milledgeville, some eighty-five miles to the west. As far as he was concerned, the prison remained a high-priority target and an important objective for the next phase of the operation.

Right Wing

“Cold and snowflakes flying,” wrote a diarist with the 11th Iowa as the Seventeenth Corps spilled from its camps into formations taking shape for the march to Gordon. A Wisconsin man in the mass noted that the “ground froze & water 1/2 an inch thick [with ice].” The units wasted little time sending out foraging parties. A Wisconsin soldier recorded stopping at a large plantation where he had “roasted Chicken Sweet Potatoes Coffee for breakfast.” Other observant Federals took notice of a change in the landscape. “We have just left the highlands,” said an Illinoisan, “and this is our first introduction to the extensive pineries and swamps that characterize the southern portion of the Empire State of the South.” Sherman’s men had crossed the fall line; from here on all the rivers led to the Atlantic Ocean.

It was late in the afternoon when the leading elements of the Seventeenth Corps entered Gordon, shooing away a few remaining state militiamen ahead of them. Gordon, also known as Station No. 17 on the Central of Georgia Railroad, was a whistle-stop town—just a couple of buildings out in the middle of nowhere. “The citizens some

what excited,” commented an Ohio diarist with decided understatement. The structures in town linked to the railroad didn’t last long, and the track not much longer. “This was a very nice railroad but is fast being destroyed,” commented an Iowan.

While they worked, some of the Yankee boys wondered where the army would go next. “If we started south or southwest when leaving Gordon we would go to Mobile [, Alabama,] but if we went east or southeast then we would join our cracker line

*

at Savanna[h],” mused an Iowa soldier. Others raided the village post office to return with armfuls of recent newspapers. “First, and all-important, was the news that Lincoln had been re-elected to the Presidency,” said an Illinois soldier. “[Second:] In order to inflame their passions, the paper contained many…scandalous narratives of robbery, rapine and murder [by Sherman’s men]…. In other columns were found inflammatory appeals from military and civil authorities, calling upon the inhabitants to harass the troops in every conceivable way.”

Gordon became a point of concentration for the Right Wing, so before long the surrounding countryside began filling with the impedimenta of war. It was, remembered a Wisconsin officer, “all…crowded and in confusion—marching troops, wagons, cannon, ambulances and horsemen being packed together in a mass.” Amidst this chaotic scene one image stood out for this officer, the sight of a “little black boy not more than seven or eight years old, running along, dodging this wagon and that horse, and crying, ‘I want my mammy! I want my mammy!’” Recalling the event long afterward, the man wondered: “Did he find her that night, or the next morning, or ever?…What became of the little fellow? I don’t know that, but I’ve often wondered about it all these years.”

Something else claimed attention as sunset approached. Said one of the many who took note of the occurrence in their journals or diaries: “Very heavy cannonading is heard in the direction of Macon.”

Some twenty miles to the east, Major General Henry C. Wayne was busy organizing the defense of the Oconee River bridge. Arriving there from Gordon, he found something to cheer him for waiting on the east

bank was Major Alfred L. Hartridge with a mixed command of cavalry, artillery, and infantry totaling 186 men. Adding the 500 or so that Wayne had shifted here, he had approximately 700 soldiers to stop Sherman’s march.

It was a daunting prospect. While the river at the bridge crossing was fringed with broad swampy banks, making it impossible for the enemy to employ his artillery, there were a number of fording places both above and below the span. Wayne estimated that he had “twenty miles at least of line to watch and guard.” There was nothing left to do but try. Wayne afterward reported that his officers and men “cheerfully prepared to do their duty and meet their fate.”

As soon as he found a working telegrapher, Wayne began bombarding Savannah with requests for munitions and rations. He also passed along whatever information came his way, including a late afternoon flash, “Heavy cannonading now going on in the direction of Macon; firing rapid.”

This day’s march spread the four divisions of the Fifteenth Corps across a broad area. The Third (Brigadier General John E. Smith) literally got off on the wrong foot in its movement toward Gordon. His men, groused a member of the 93rd Illinois, “marched about a mile and turned around…. Old Gen. Smith got a great many cussings from the boys for taking us on the wrong road.” The relatively unencumbered division overtook the slower-moving tail end of the Seventeenth Corps, forcing the Fifteenth Corps boys to tramp “through the woods and plantations, moving abreast with the Seventeenth Corps.”

Once the Third Division segued onto the railroad right of way, the men were set to wrecking it. “The rails are laid on stringers,” reported a soldier in the 10th Iowa. According to an officer overseeing the operation, “the plan adopted was to string out two or three regiments on one side of the track, and by word of command have every man seize hold of a cross tie or the stringer, and when all were ready the word was given…and in a few seconds the track rose from its bed; the stringers were knocked loose from the ties, and the work of piling the ties across the stringers and building fires was soon accomplished, the heat expanded the rails while spiked fast.”

Coming in behind the Third Division was Corse’s Fourth, still shep

herding the slothful wagon trains. “We enjoyed a snow storm in Central Georgia this morning,” wrote an Ohio soldier in his journal. It was about 9:00

A.M

., added an Iowan, when the sky “cleared up & the old Sun came out and with its gentle rays dispelled the blue Noses & white Ears.” The slow pace gave lots of time for foraging, so the men did well; a Hoosier recorded finding plenty of pork, while an Illinois boy in the 66th Regiment proclaimed it a “Yankee picnic through Georgia.”

What almost all of Corse’s troops remembered of this day’s march was the Herculean struggle with the wheeled transport. “Roads very bad, trains and artillery mired in mud and men detailed to help extract them,” wrote an Iowa man. “As the mules drop down from exhaustion they are rolled out to one side and left more dead than alive,” attested a member of the 50th Illinois. The valuable pontoon train was a significant problem. “Every one of the pontoon teams are stuck in the mud,” complained an Iowan. An Ohio man recalled it as “hard pulling,” while an Illinoisan added, “wagons broke, soldiers laughed, teamsters swore & so it went.”

For the Second Division (Brigadier General William B. Hazen), which had spent the night camped north of Griswoldville, today’s tramp was east and south toward Irwinton. It was along this route that one of the more clearly documented cases of civil abuse occurred. According to Lieutenant Thomas Taylor of the 47th Ohio, a party of men in Union uniform entered a house “and after robbing the family of every thing to eat, deliberately proceeded to break jars, dishes, [window] sashes, furniture, &c…, then robbed the beds of their bedding, wardrobes of their clothing and cut open mattresses…. To complete their inhuman and fiendish act [the vandals finished] by driving the lady big with child, her innocent little children and her aged mother from the house.” Assigned to return the occupants to their home and to protect them while the division remained nearby, Lieutenant Taylor admitted that the “heart rending grief [they expressed] added to the other touching scenes around filled me too full for utterance.”

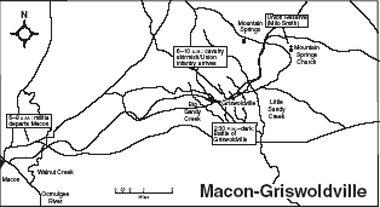

Griswoldville

It was cold as Lieutenant General Richard Taylor stepped off the Columbus train onto the Macon railroad depot platform early in the

morning. “It was the bitterest weather I remember in this latitude,” Taylor later wrote. “The ground was frozen and some snow was falling.” Waiting for him was stout Howell Cobb, who commanded the state troops in town and was a political figure of commanding importance. Cobb immediately volunteered that the enemy had been sighted just a dozen miles outside Macon not twelve hours before. He was anxious to take Taylor on an inspection of the defensive fortifications, but the veteran officer stopped the proceedings with a question. “I asked what force he had to defend the place,” Taylor said. When Cobb told him how meager it was, Taylor smiled and suggested that everyone—the party at the railroad station and those working on the city’s defenses—go inside near a fire. “Macon,” Taylor declared, “was the safest place in Georgia.”

This did not sit well with the member of Cobb’s entourage tasked with directing the construction of the city’s defensive works, who immediately challenged the outsider’s assessment. “The enemy was but twelve miles from you at noon of yesterday,” Taylor explained with great patience. “Had he intended coming to Macon, you would have seen him last evening, before you had time to strengthen works or remove stores.” It was as if a great weight had been lifted from Howell Cobb’s shoulders. With his own smile he proposed that they repair indoors for some breakfast, a suggestion that Richard Taylor thought was eminently sensible.